Universal Credit an attack on the working class.

Universal credit along with all its failures, along with the hardship to all it touches from the unemployed to the working poor even the disabled is still been rolled out worts and all. We still see it continue to plague the nations poor. Roll out is a failure even the cost is terrifying. Why don’t they just stop it?

Is it just bad planning? A glitch in such a big project that will be rectified later after the rollout? Don’t hold your breath this thing is designed that way!

When you understand where this model came from and the reason behind it you understand there is never going to be a fluid system of welfare benefits.

We see stories like this now becoming a common occurrence an all too familiar tale as we see the roll-out of Universal Credit.

The employment office punished me because I had a stroke:

“Of course, after I was released from the hospital, I was worried about a lot: How do I cope with my everyday life? Can I still bring my daughter to me on the weekends? Can I take care of her?

I expected the worst. However, not that the Jobcenter would punish me because I did not notice my training date on the day of my stroke.

But that’s exactly what happened.

With my 80 percent sanction, I got exactly 163 euros for the whole of December.I have to pay electricity and food – on the weekends I have to feed my daughter. And then there’s Christmas too.

I’m probably not an isolated case.

For sanctions, our job centers are fast. In the first quarter of this year alone, job centres occupied around 4.3 million recipients with over 315,000 sanctions.

Just before Christmas, it got me now.I have to save so that we can eat in the days after Christmas.”

This sounds like a to familiar tale of sanctions and the Universal credit system except it’s not it is from a the carbon copy Hertz system.

Another example would be:”I have to borrow toilet paper” – as the employment office has messed me up Christmas” While all the people scouring the shops for gifts and thinking about which menu they want to eat on Christmas Eve, I’m glad if I can scratch at the end of each month still a few euros for some food and toilet paper.

Because punctually at Christmas time, the Jobcentre sanctioned me and canceled 30 percent of the salary. What that really means for me and my family, few suspect.

“I CAN’T EVEN BUY TOILET PAPER” – THE POOREST ARE MADE EVEN POORER”

I am 32 years old As a benefit recipient, I have to fight against prejudices time and again. Many people think unemployed people are just lazy and have an easy life to be jealous of .

MANY PEOPLE THINK THE UNEMPLOYED ARE JUST LAZY!

Slogans like “You live at the expense of taxpayers who have to work hard for their money …” or “We work all day and you have all the day” I have heard more often.

You would be forgiven for believing these are statements and press realises about the Government’s new Universal credit but in fact, they are not!

These are press releases from German Newspapers relating to people’s experience with the German Benefit system known as Hartz IV no matter what you are told the UK’s universal credit system is a carbon copy and adopted by the UK with all the flaws intact, flaws designed to bring hardship to the working class.

It is an inhumane, pro-capitalist, ‘neoliberal’ social and economic instrument tailored for the interests of corporations, and unnecessarily harsh and stingy towards unemployed workers.

Where did the idea of Universal credit come from and what’s behind it?

These are statements and press articles from the recipients of the ‘German Hartz iv’ benefits system. You can read the full harrowing stories from the victims of Hartz iv the German benefits system but the most shocking thing is this system has been adopted by the UK Government knowing full well all its flaws and failures. Full story Huffington post-German edition

Universal credit is a carbon copy of a failed model.

It may surprise to some that the Tory Government are not the only EU Government that brings hardship and pain to the people who find themselves in a position of having to claim benefits or fall back on the state to help them survive.

But what is not a surprising is the fact that the model they have Corbyn copied is flawed, designed not to save on overall welfare cost but ultimately it is an ideological decision an inhumane, pro-capitalist, ‘neoliberal’ social and economic instrument tailored for the interests of corporations, and unnecessarily harsh and stingy towards unemployed workers and the working poor an attack on the disabled and single parents.

To some, it will probably just be confirmation of the hostility and near social cleansing, the Tories are carrying out on the working class.

The fact is the UK Government are just using a ‘carbon copy’ of the failed German Hartz IV. the harsh universal credit system that as caused nothing but pain and hardship for the German people unfortunate enough to have found themselves having to fall back on the state.

A little about Hartz IV

The Hartz IV reforms, which were passed into law in 2003 and took effect in January 2005, significantly toughened the conditions under which people could claim welfare or unemployment benefits. They require benefits recipients to regularly attend meetings with a jobcentre advisor and show they’re actively looking for work or enrolled in approved work-preparatory skills-training programs.

The advisor is empowered to withhold benefits if the claimant refuses a job – even if the job is not what the claimant would like to do. Even a single failure to show up for job-centre meetings can result in partial loss of benefits – and regularly failing to show up results in their complete cancellation.

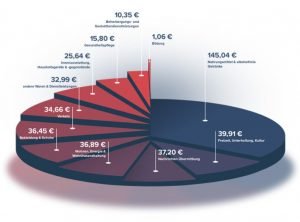

Benefits are set at rates intended to secure a ‘socio-cultural minimum’:

They’re carefully calculated to be just enough to get by on, with no frills. Benefits packages include the government paying for the rent on a modest apartment, medical insurance, and a monthly stipend.

Making work pay?

The clear intent of the Hartz IV package is to avoid making life too comfortable for benefits recipients, and to nudge or push them into employment – even if poorly paid. This is reflected in the government’s Hartz IV slogan: “Fördern und Fordern,” translated “Encourage and demand” i.e. support recipients, yet make demands on them, in the manner of a stern parent.

Hartz IV was the fourth in a series of business-friendly labor-market reforms enacted in 2002 and 2003, all named after Peter Hartz, the head of an SPD government-appointed labor market reform commission. Since the reforms, the rate of unemployment in Germany has gradually decreased, except for a temporary setback in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. As of 2016, the ‘employment rate,’ i.e. the percentage of adult citizens in work in Germany, was at its highest in post-war history.

Mainstream Conservative politicians, including Chancellor Angela Merkel, support the Hartz reforms, and have no intention of repealing or softening them. They attribute Germany’s comparative economic success over the past decade in significant part to the reforms.

Germany’s labour market and welfare reforms of the early 2000s have gained an outsized importance over time. For some, these reforms put an end to Germany’s social market economy and pushed millions into insecure, low wage jobs. For others, notably many international observers, these ‘Hartz reforms’ are one if not the main reason why Germany – formerly known as the ‘sick man of Europe’ – is now Europe’s export powerhouse and strongest economy.

The importance of this debate can hardly be overstated. On the issue of ‘social justice’. The Hartz reforms at the centre in Europe, no other narrative has so persistently shaped the response to the ongoing euro crisis as the idea that some countries struggle because they have lost their ‘competitiveness’, and they should therefore reform like Germany in order to grow and reduce unemployment.

Rage on the left

It has become a standard trope of the German left that Hartz IV is an inhumane, pro-capitalist, ‘neoliberal’ social and economic instrument tailored for the interests of corporations, and unnecessarily harsh and stingy towards unemployed workers.

On the left, the coercive provisions of Hartz IV are seen as a way of humiliating the unemployed and squeezing the poor. Amongst leftists, the chimeric political-economic vision of an ‘unconditional basic income’ (UBI) has been gaining ground in recent years.

Many people who had reliably voted for the SPD prior to 2005 remain so disgruntled and enraged by the party’s perceived betrayal of working-class interests that they refuse to believe the electoral campaign commitments of the SPD leader, Martin Schulz

Again we have to stop and again the question is posed if Hartz is so bad why did the UK adopt it?

Poverty, homelessness on the rise despite German affluence

Slums like the favelas in Brazil don’t exist in Germany. Poverty and homelessness are only visible at second glance, in part because the social decline is less obvious.

Germany is a welfare state. The network of social welfare via state, local and church outlets is more densely woven than in most comparable affluent societies. The economy is humming along, unemployment is at a historic low of under six percent, energy and food prices are lower than in many other European country.

But poverty exists in Germany, although without slums – because running water, electricity, sewage systems and garbage collection are given even in the most basic lodgings.

The reasons for poverty, and who is affected:

– At present, about 860,000 people in Germany are homeless, according to estimates by the Federal Association for the Support of the Homeless (BAG W.) Some live in the streets, but more than 800,000 stay with friends or spend the nights in emergency shelters.

– About 52,000 people in Germany live in the streets, without a roof over their heads – that’s a total of six percent of the people regarded as homeless.

– About 440,000 refugees have a legal right to an apartment. At present, they are still housed in mass accommodation.

– Women, families and migrants are hit the hardest. They are more frequently in danger of losing the roofs over their heads, even if they are rented apartments.

The state’s retreat from subsidized housing is one of the reasons. Thirty years ago, West Germany alone had four million rent-controlled apartments. Today, in a Germany that has grown much larger, that number has dwindled to 1.3 million. Affordable housing is rare; the market dictates the prices.

– Small apartments are particularly expensive. They are fought over in a country that meanwhile counts about 17 million one-person households with only 5.2 million one- and two-room apartments on the market. Extreme increases in rents in urban areas are the consequence.

This is carbon copy neoliberalism. A tool of oppression an attack on the working class.

France: “Nuit Debout” is the name of the movement, “Night of the Upright” – For weeks every week French protesters against social injustice – The protests against the reform of the labor market in France has become a new movement. Every night activists occupy the Place de la République.

Nuit Debout is a French social movement that began on 31 March 2016, arising out of protests against proposed labor reforms known as the El Khomri law or Loi travail.

When Hollande received Peter Hartz at the Elysée Palace January 2014, the outcry was great. A Hartz IV reform for France? However, even the conservative papers wrote of devastating consequences in Germany: one-euro jobs, impoverished layers of the population, a new precariat. Therefore, the currently contested French reform is far removed from the painful cuts of ‘Agenda 2010’, the world writes.

Agenda 2010 was a legislative package of labor market and welfare reforms intended to reduce unemployment and jumpstart Germany’s economy.

What did the reforms do?

The main changes implemented under Agenda 2010 include:

- Drastic cuts to welfare budget

- Tax breaks to workers and corporations

- Weakening the then-stricter labor laws to allow easier hiring and firing of employees

- Changing the rules to allow for more part-time and temporary work

- Creating social benefit program called “Hartz IV” that merged unemployment and welfare benefits

- Reducing the amount of time a person could receive unemployment benefits

The reforms also called for raising the federal retirement age to 67. The age is still currently set at 65 but is planned to reach 67 by the year 2029.

The number of low-paid and part-time jobs in Germany has grown significantly since the reforms were put in place. The number of limited-term contracts also expanded, impacting workers on all levels, leading to frustration about not being able to plan for the future. It all sounds very familiar here in the UK

In France, tens of thousands are homeless despite jobs. A study published by the French statistics office Insee on the employment situation of French-speaking homeless people comes to a surprising result: One in four homeless people in France has a job. The salary is not enough to hold an apartment. Half of the homeless women work as domestic help, childcare or nursing.

In France Macron now sees the rise of the yellow vest or more accurately the Gilets Jaunes

The election of Emmanuel Macron tested the validity of this narrative, as he is vowed to reform France along German lines. This narrative turned out to be false, he failed to deliver growth and employment. What he has delivered is a near Revolution following his neoliberal anti working-class reforms.

A sober look at the German reforms shows that their economic impact was modest.

They targeted weaknesses in Germany’s labour market and benefits system suggesting these reasons:

- combined unemployment and social assistance into a single system, to help more people find jobs or retrain;

- curbed incentives to ‘retire early’ by preventing people from claiming generous unemployment benefits before reaching retirement age, thus increasing the employment rate among older workers;

- made job search, training and job centres more efficient, which helped to reduce unemployment by an estimated 1.5 percentage points; and

- provided more incentives to take up work, which increased temporary and marginal employment.

There were fewer negative side effects than are commonly attributed to the reforms. For example, the large low-wage sector – Germany has the largest in the EU after the Baltic States, Poland and Romania predates the reforms.

But the number of people in insecure jobs and at risk of poverty increased after the reforms. The effect on income inequality is ambiguous.

Many argue that one consequence of the Hartz reforms was wage restraint, which is why the rest of Europe should follow Germany’s lead in order to gain ‘competitiveness’.

But wage restraint started in 1995, not with the reforms in 2004. It was mostly a consequence of high unemployment, globalisation and the threat of offshoring and outsourcing by businesses.

Only low wages were pushed down further as a consequence of the reforms.

Exactly 15 years ago today, Germany’s labour market was subjected to the first of the so-called Hartz IV reforms. Brought about by the smooth centre-left chancellor Gerhard Schröder, it was a watershed moment that changed the way the German government deals with poverty.

The changes were riddled with the kind of Anglicisms that German officialdom likes to deploy for any modernisation. In the past decade, unemployed Germans have been bewildered with a kaleidoscope of new “English” terms, from “Jobcentre” to “Personal Service Agentur” to “Mini-Job” to “Bridge System”. But the measures recommended by the Hartz commission – named after its chairman, former Volkswagen executive Peter Hartz – boiled to down to this:

“THE BUNDLING OF UNEMPLOYMENT BENEFITS AND SOCIAL WELFARE BENEFITS INTO ONE NEAT PACKAGE.”

A basic principle of social security in Germany is this: The best incentive to get people into work is to cut their payments if they miss an appointment, or fail to finish a training course, or refuse to sign an “integration agreement” in which they pledge to do all they can to find a job.

But this simply doesn’t work, says the Sanktionsfrei (“sanction-free”) organization.

“Not only does the pressure created by the threat of sanctions lead more people to fall out of the system completely, it even demotivates those who aren’t even being sanctioned.”

To prove its point, the organization launched a study on Thursday to find out what effect sanction-free support has on people. Starting in February 2019 and for the next three years, 250 randomly-chosen recipients of Hartz IV financial assistance — the system of German long-term unemployment benefits or welfare support — will get any sanctions immediately reimbursed by the organization, no questions asked.

The scheme is called HartzPlus.

The organization will then record the psychological effects of this newfound security in periodical questionnaires that the participants fill out. A control group of another 250 Hartz IV recipients will get no such safety net, but still out the forms.

Rainer Wieland, professor of work psychology at the Schumpeter School of Business and Economics, Wuppertal, who is running the academic side of the study and will digest the data in three year’s time.

The Hartz IV system, he said, has a major psychological impact on people: “Uncertainty, unpredictability, and uncontrollability — the feeling, so to speak, of not having one’s world under control,” he said.

“That’s one of the strongest stress factors we know. I can quote you any number of studies that make clear uncontrollability and unpredictability has consequences, and one of those consequences is demotivation.”

This is an extract from German media in 2004. Sound familiar?

Meanwhile, job-centres and municipal welfare offices did not know enough about their clients to determine eligibility under the new rules. They have sent out 16-page questionnaires to some 3.8m long-term unemployed and welfare recipients, asking for information about everything from the income of other family members and personal savings to health insurance and special dietary needs.

Data-gathering on such a scale is quite a feat, but the calculation of benefits is even harder. Coding German social-security law is a programmer’s nightmare. It proved possible to meet such a tight deadline only because Prosoz, a German software firm, had already developed the core of the application.

New software technologies were used to produce a service accessible via the internet. For the first time, Germany will have a near-complete database of its less fortunate, making it easier to evaluate training and to detect fraud.

The biggest challenge is to merge parts of the job-centres with the welfare offices. In most places, they will jointly administer the new benefit and help clients find work. But the two bureaucracies have different cultures: one is hierarchical and has focused on paying benefits, while the other sees its main task as social caretaking and has a reputation for independence.

So far, the whole operation has gone surprisingly smoothly. With a week to go before the deadline, 94% of the questionnaires sent out had come back, and benefit statements for 2.2m households had been issued. The computer system, after crashing repeatedly in October and proving unable to deal with complex cases, is more stable. Better still, the threat of not getting the new benefit has prompted many unemployed to look harder for work.

Yet much could still go wrong. Many of those who have had benefit statements claim that the calculations are wrong. Some fear that protests against Hartz could revive, or even turn violent. And it remains to be seen if the software will make the correct payments.

Pessimists expect a technical disaster comparable to Germany’s ill-fated road-toll system for lorries. Worse, unemployment may go up before it goes down, because welfare recipients who can work will now be classed as unemployed.

The stakes are high. If Hartz IV succeeds, Germany will have taken a big step towards helping its army of long-term unemployed off the dole and into work. If it fails, there will be pressure to break up the Federal Employment Agency or privatise it.

2004 Hartz and minds

A new and controversial law takes effect this weekend

This is the motivation behind the UK adoption

What is hard to overlook is that the Hartz reforms have had two social effects. First, they have helped to accelerate inequality in Germany. According to an April 2012 OECD report, “Germany is the only [EU] country that has seen an increase in labour earnings inequality from the mid-1990s to the end 2000s driven by increasing inequality in the bottom half of the distribution.”

Knowing this and knowing the failure behind Hertz why is the UK going ahead with this Carbon Copy Universal credit?

A bigger question would be why are we repeating the same mistakes, after all it’s not new. The Government certainly have a failed model they have simply copied Universal credit from the failed German model so why did they not see the issues on both roll out and the real human issues caused by this system?

Hartz IV: Beneficiaries of Unemployment Benefit II on an annual average from 2010 to 2018 *

The statistics show the average number of beneficiaries of Unemployment Benefit II from 2010 to 2018 *. In 2018, an average of 4,156,783 persons received unemployment benefit II in Germany. Unemployment Benefit II (Alg II) represents basic benefits for employable persons in

need of assistance under SGB II and was introduced by the Hartz IV Act at the beginning of 2005 with the merger of the former unemployment assistance and social assistance. Alg II is available to all eligible persons entitled to benefits at the age of 15 years up to the statutory retirement age of 65 to 67 years. Unemployed people in need of benefits receive social benefits if they are in their community of need (see the Number of communities of need in Germany ) at least one able-bodied person in need of care lives. Unemployment Benefit II and Social Benefit are benefits under the SGB II, which are to ensure basic security of livelihood. The persons in need communities (this includes the beneficiaries according to the SGB II and the non-entitled) are colloquially often referred to as Hartz IV recipients. See also the time series to the beneficiaries of unemployment benefits and social assistance and people in communities of need.

See also the rule sets of Hartz IV from January 2017 and the development of the ruleset since the year 2005.

Chancellor Gerhard Schröder (of the SPD) introduced Hartz IV in 2003 — a decision that has tormented the centre-left party ever since.

Around 4.2 million Germans now receive Hartz IV (not including their 2 million children and other dependents), and every year 450,000 of those received sanctions amounting to between €41 and €416 — the latter amounting to 100 percent of their income.

Anger over Schröder’s “Agenda 2010” reforms split the SPD and indirectly caused the foundation in 2007 of the socialist Left party, one of whose policies today is the abolition of Hartz IV in favour of sanction-free basic unemployment security of €1,050 a month. Meanwhile, a joint bid to end Hartz IV sanctions between the Left and the Green parties failed in the Bundestag this summer.

Still, SPD leader Andrea Nahles is currently gathering suggestions for a new social security package, and a consensus is building in the party that sanctions should be scrapped. “There’s a lot happening!” says Lothar Binding, the SPD’s financial policy spokesman in the Bundestag. He wouldn’t get rid of sanctions altogether, but he thinks they need to be reduced and used much more sparingly.

Binding argues that sanctioned people should receive better psychological care.

“These are often people who simply can’t organize themselves properly in their lives, It’s not acceptable that the state offers support below the minimum. That has nothing to do with humanity anymore.”

The Green party is charting a more radical route. “Hartz IV has caused a lot of problems,” Sven Lehmann, the Greens’ labor spokesman, told DW. “It’s been in force for 15 years, and we know that poverty has grown, the low-wage sector has grown, and the middle classes are scared of falling into that system and then won’t be able to decide what they want to do.” Removing sanctions, and thus removing fear, can only help the economy, he added.

The immediate effect was to leave those living on benefits worse off (as of 2013, the standard rate for a single person is €382 a month, plus the cost of “adequate housing” and healthcare). But the new element that brought the most profound change was the contract, drawn up between the “jobseeker” and the “Jobcenter”, which defined what each party promised to do to get the jobseeker back on somebody’s payroll.

This was coupled with “sanctions” – in other words, benefit cuts – if the jobseeker failed to keep up his or her side of the bargain. With those two measures, Germany came to accept the modern interpretation of the word “incentive” in the job market:

THE DOCTRINE THAT POOR PEOPLE WILL ONLY WORK IF THEY ARE THEY ARE NOT GIVEN MONEY.

What is hard to overlook is that the Hartz reforms have had two social effects. First, they have helped to accelerate inequality in Germany. According to an April 2012 OECD report, “Germany is the only [EU] country that has seen an increase in labour earnings inequality from the mid-1990s to the end 2000s driven by increasing inequality in the bottom half of the distribution.” The report goes on to point to “a set of reforms in 2003 meant to increase the flexibility of the labour market” which help to explain the “wage moderation”.

“Work on-call – The Hartz Commission wants to push the unemployed into temporary employment. The industry is already looking forward ”

Translated agency workers on zero hour contracts.

Peter Harz, known from the named after him resin IV was of the opinion that temporary work for many is a bridge, a probationary period, a settling into the working life. The way to a steady job. For corporations, it meant that expensive collective agreements applicable to the core workforce could be circumvented, as well as dismissal protection. Downtime of the temporary workers is charged to the rental company (Agency Workers).

In Germany, 7.6 million people live from minimum income.

Hartz IV, basic benefits in old age, asylum seeker benefits: every eleventh person in Germany lived in 2017 from state aid

- Hartz IV – officially unemployment benefit II and social benefits: Around 5.9 million people received money from this benefit. That is a decline of 0.7 percent compared to 2016.

Rage on the left

It has become a standard trope of the German left that Hartz IV is an inhumane, pro-capitalist, ‘neoliberal’ social and economic instrument tailored for the interests of corporations, and unnecessarily harsh and stingy towards unemployed workers.

On the left, the coercive provisions of Hartz IV are seen as a way of humiliating the unemployed and squeezing the poor. Amongst leftists, the chimeric political-economic vision of an ‘unconditional basic income’ (UBI) has been gaining ground in recent years.

Again we ask after 15 years since its introduction knowing how this German model is such a failure, why the British Government have adopted it?

Please read the UN special rapporteur on the UK Link: HereSupport Labour Heartlands

Help Us Sustain Ad-Free Journalism

Sorry, I Need To Put Out the Begging Bowl

Independent Journalism Needs You

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands