Oligarchy or Democracy

Forward: This is an extremely long article, it has been shortened many times but as is the nature of such posts it continued to grow. It’s difficult to put into an article all the history behind our common struggle, the emancipation of the working class is not a short story and is still being fought.

I think democracy is the most revolutionary thing in the world, because if you have power you use it to meet the needs of you and your community.

–TONY BENN

Understanding the history of democracy and the fight the working class have had in gaining some degree of that powerful form of government, is essential to understanding how close to losing this battle we are.

“You have to know the past to understand the present.” ― Carl Sagan, astronomer, planetary scientist, cosmologist, astrophysicist.

Knowing the past is as important in politics as it is in astrophysics, it helps us understand how we got to this point, who we are and more importantly, what we are actually fighting for.

Sometimes it can all get a little confusing, and to be fair in the main, that’s the intention, the establishment doesn’t want a too well educated, socially aware, united working class. They don’t want us to understand what’s really going on, or to be able to identify the common enemy, we might even stop fighting amongst ourselves if we did.

This enemy is the “oligarchy,” commonly known as the few; These are the elite who see democracy as the enemy, they believe that people should be managed not represented. This is an age-long conflict with many battles. There have been ebbs and flows but right now it’s entering another transitional point, a storm is brewing and the oligarchy are winning.

So what is an Oligarch?

Popular belief and the mainstream media would have us think that the word Oligarch was Russian, indeed there is always much talk of Russian oligarchs mainly concerning their great power and influence exerted throughout all spheres of business, media and the political world.

The mere mention of the word Russian oligarchs throws a subconscious image of a Bond-like villain with a shady accent and henchmen to boot. The terminology Russian oligarchs also makes for a good scapegoat and a great news story when international relations get a little strained.

Of course, the mainstream media would have us believe a lot of things that have no context to the truth or reality. The word oligarchy is much older and far more sinister than the media use of the word would lead you to believe.

Where it may be very true the Russian oligarchs are rich and powerful people that wield great influence, however in our case, when we talk of Oligarchs we are talking about a much more powerful organisation of Oligarchs. These particular Oligarchs are the old breed, they are vastly more powerful and in the main a little less ostentatious.

A short history of the concept of the oligarchy.

Over 2,300 years ago, Aristotle coined the term oligarchy as he contemplated the forms of state governance.

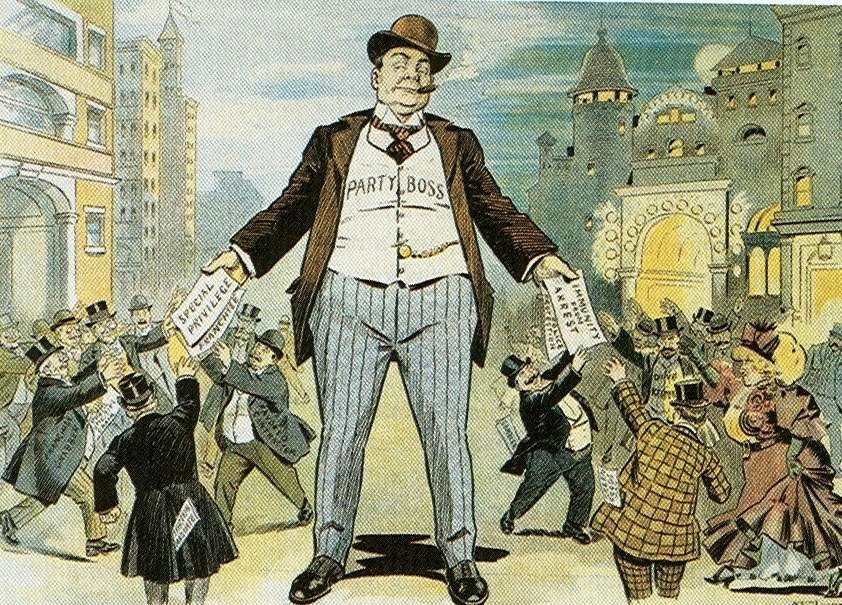

Like aristocracy, oligarchy means rule by the few, as contrasted with democracy, which is rule by the people. From Aristotle’s time until the early 20th century, the concept of an oligarchy – and oligarchs – was well known, examples were the feudal Barons of the UK or the modern Robber Barrons of 19th century North America, those that ruled for the few, by the few.

The oligarchy is that “few” in the mantra, “for the many, not the few.” Until the mid 20th century it was common practice to use the word oligarchy to describe the one percent, the few. Like many such words, they drop out of favour and are replaced by something different or new but not necessarily better or more precise.

It was while examining the question of the nature of democracy and its foundations I came across Plato’s Republic and his interpretations of the five regimes.

The philosopher discusses five types of regimes. They are Aristocracy, Timocracy, Oligarchy, Democracy, and Tyranny. Plato also assigns a man to each of these regimes to illustrate what they stand for. The tyrannical man would represent Tyranny, for example. According to Plato these five regimes progressively degenerate starting with ‘Aristocracy’ at the top and ‘Tyranny’ at the bottom.

Where the ‘Five Regimes’ are all extremely relevant the two regimes we are interested in are those of Oligarchy and Democracy. More so the history and continued fight between the two.

Oligarchy wrote Plato is government by “greedy men” who love money so much that “they are reluctant to pay taxes” for the common good (Republic VIII, 551e). Although the Greek word “oligarchy“ literally means government by the few, Plato spins the word to mean the wealthy few. He thus distinguishes Oligarchy from Timocracy (from the Greek “timos“ or honour), which was also a form of government by the few. For Plato, Timocracy is government by a few virtuous men who love honour, whereas Oligarchy is government by a few rich men who love power and wealth.

Oligarchs believe that the wealth of a society should be redistributed to themselves and their rich cronies, while the rest of the society is reduced to poverty. In fact, observes Plato, nearly all the citizens of an oligarchy are impoverished, except for those in the ruling class who subvert the laws to protect their own interests, leaving the majority of the populace burdened by debt and disenfranchised.

Sounds very familiar.

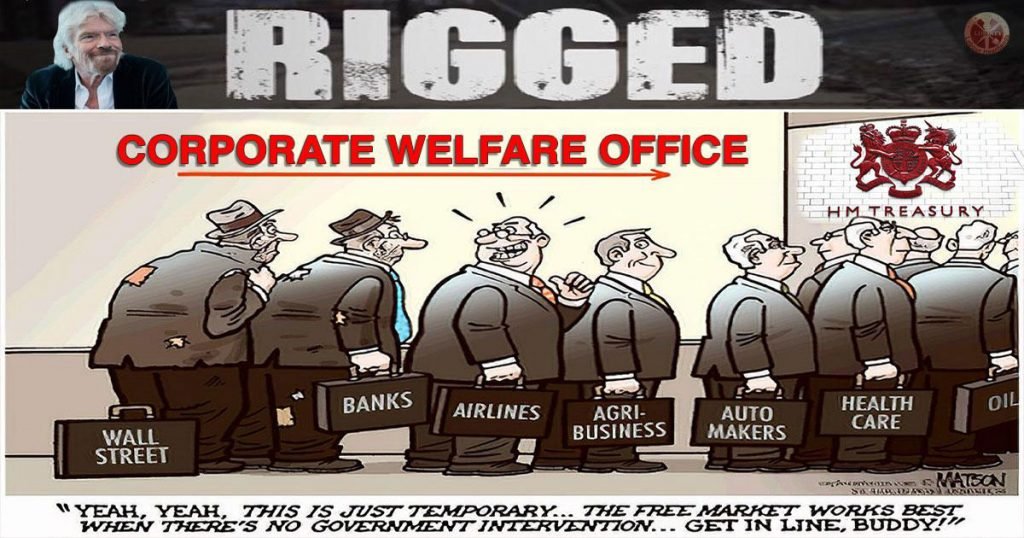

There can be no doubt that throughout the Coronavirus pandemic cronyism and corruption has been rife. Covid has provided cover for the Oligarchs of the world to advance their wealth tenfold.

They have cynically used the pandemic to carry out the largest transference of public wealth into private hands since the Sack of Rome in 410 AD.

Labour’s shadow education secretary may have cynically suggested the Covid-19 pandemic could be a “good crisis” for her party, on a political level and it seemed an extremely crass statement to make while the rest of the population suffered to one degree or another, some losing family and loved ones.

However, her words did ring true for the Oligarchy who used the crisis to its advantage and positively thrived.

A report by Swiss bank UBS found that billionaires increased their wealth by more than a quarter (27.5%) at the height of the crisis from April to July, just as millions of people around the world lost their jobs or were struggling to get by on government schemes.

The stats show us the world’s billionaires “did extremely well” during the coronavirus pandemic growing their already huge fortunes to a record high of £7.8tn.

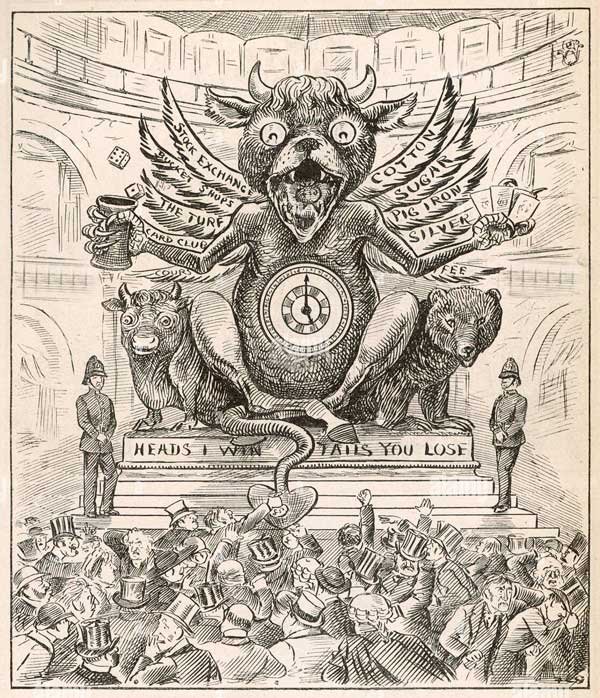

The oligarchy uses every crisis to its advantage, they hold all the cards.

It’s us against them!

The common struggle of the many, against the few!

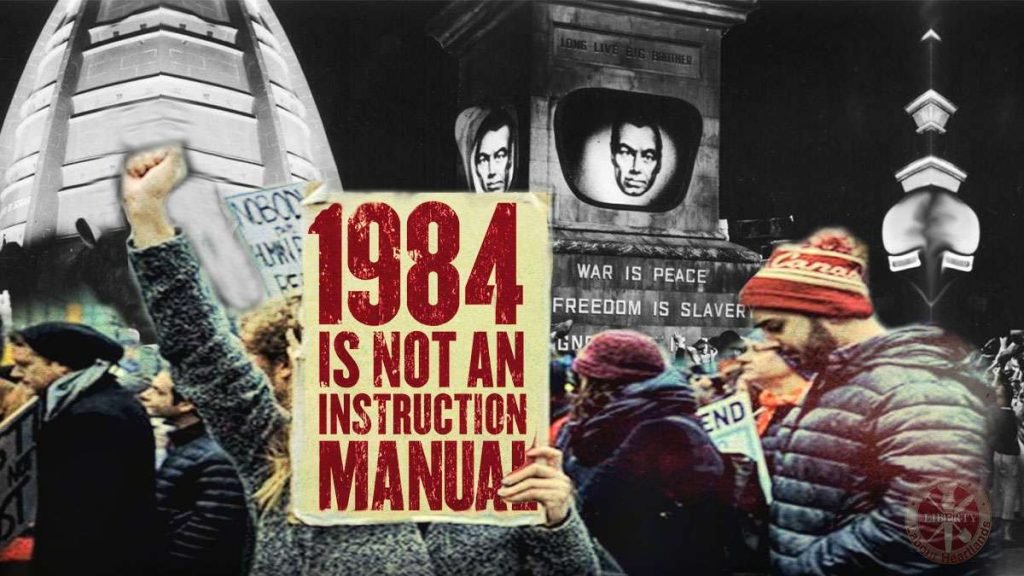

There is a constant battle between the Oligarchy and Democracy being waged.

Understanding the oligarchy helps to know a little about how ancient philosophers described the governance of men and the shortfalls of each regime.

Plato suggests Oligarchy, degenerates into a Democracy where freedom is the supreme good but warns freedom is also slavery.

According to Plato in a democracy, the lower class grows bigger and bigger. The poor become the majority allowing them to vote into law populist policies that suit the many but not necessarily what is right.

More often than not, populist parties are considered to be a threat to stability, Plato asserts, equality brings power-seeking individuals who are motivated by personal gain. Populist leaders and parties can have a negative impact on the separation of power, the rule of law, and minority rights. They can be highly corruptible, and this can eventually lead to tyranny.

Plato does not believe that democracy is the best form of government. According to him, equality brings power-seeking individuals who are motivated by personal gain. They can be highly corruptible, and this can eventually lead to tyranny. This form of government is unstable, and it lacks leaders with proper skills and morals. Without able and virtuous leaders, who come and go, it is not a good form of government. He sees democracy as dangerous as it motivates the poor against the wealthy rulers. It prioritizes wealth and property accumulation.

A democracy would simply vote away the accumulated power of the Oligarchy and proclaim a redistribution of wealth through the democratic process of the ballot.

With that view in mind, it’s understandable why the Oligarchy will cling to power through whatever means possible.

Aristotle however argued that oligarchies and democracies are the most common forms of government, with much in common except their allocation of power; and thus he spends a lot of time discussing them.

The real difference between democracy and oligarchy is poverty and wealth. Wherever men rule by reason of their wealth, whether they be few or many, that is an oligarchy, and where the poor rule, that is a democracy.

It is important to note that Aristotle did not consider oligarchies and democracies as inherently bad. Even though they govern in the interest of those who hold the power, they are capable of producing livable societies, unlike tyranny, that form of government all the philosophers agreed on is the lowest form of government.

In many cases, even governments that have democracies or monarchies actually have oligarchies controlling them. In this case, a government may be structured as having democratic or monarchical systems but is actually influenced by rich, powerful, or persuasive people, families, or corporations that can levy a good amount of authority.

We can look around at government today realising we live under one of those regimes; the only thing we are certain of is our system is not a true democracy.

The Age of Enlightenment.

Looking back can help give a clearer perspective.

Over the last three hundred years, people have made great strides to overthrow the tyranny of oppressive feudal systems.

The Age of Enlightenment was a philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe in the 18th century. Centred on the idea that reason is the primary source of authority and legitimacy, this movement advocated such ideals as liberty, progress, tolerance, fraternity, constitutional government, and separation of church and state.

In the mid-18th century, Europe witnessed an explosion of philosophic and scientific activity that challenged traditional doctrines and dogmas.

The philosophic movement was led by Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who argued for a society based upon reason rather than faith and Catholic doctrine, for a new civil order based on natural law, and for science-based on experiments and observation.

The political philosopher Montesquieu introduced the idea of a separation of powers in a government, a concept which was enthusiastically adopted by the authors of the United States Constitution.

There were two distinct lines of Enlightenment thought. The radical enlightenment, inspired by the philosophy of Spinoza, advocated democracy, individual liberty, freedom of expression, and eradication of religious authority.

A second, more moderate variety, supported by René Descartes, John Locke, Christian Wolff, Isaac Newton and others, sought accommodation between reform and the traditional systems of power and faith.

The impetus for the transition to the Age of Enlightenment in all countries is the rejection of the feudal way of life, the transition to a more democratic system.

Enlightenment brought to life the notion of Equality. That notion became the key to further cultural development.

The fact that all people are initially equal to each other and have the same rights to further development as individuals, and served as the basis for creating the ideals of the Enlightenment. Was the idea of this era, which is often called the “century of Reason.” According to many thinkers, the Enlightenment is the main engine of social progress.

The evolution of British democracy.

The evolution of British democracy begins as a study of our own experience, each country can best begin by examining its own history and the struggles of its people for social, economic and political progress.

These have been built on from the Peasants Revolt of 1381, where the Reverend John Ball, with his liberation theology, allied himself to a popular uprising alongside Wat Tyler, the peasant leader, that resistance still holds within the British psyche, it still battles against the yoke of tyranny it felt the establishment hold.

The English civil war broke the chains of feudalism in many ways casting off the yoke and opening new ideas.

The Levellers were born directly from that civil war they had called for universal manhood suffrage, equality between the sexes, biennial Parliaments, the sovereignty of the people, recall of representatives and even an attack on property.’

The Diggers were a small group who preached and attempted to practise a ‘primitive communism’, based on the claim that the land belonged to the whole people of England. They had extended the call for suffrage to be truly universal including women in their rights to vote.

This claim on land was supported by the interesting historical argument that William the Conqueror had “turned the English out of their birthrights, and compelled them for necessity to be servants to him and to his Norman soldiers”.

The English civil war was thus regarded as the reconquest of England by the English people. In the theological language of the time, Winstanley urged that this political reconquest needed a social revolution to complete it and that otherwise, the essential quality of monarchy remained. (Source ) Peter Ackroyd, The Civil War (2014)

It is at these points in history the argument can be made that Democracy has flourished across the world since medieval times. Democracy, in short, is a system of political beliefs which emphasises the rights of the individual, giving them the power and freedom to choose how they are ruled.

It has various sub-definitions, extending across the range of different ‘types’ of democracies, but fundamentally it shows the same basic concern for social and political equality.

It has become one of the cornerstone characteristics of the ‘free world’, often synonymously associated with the concept of a civilised nation. In this way, it opposes the political systems which existed during the middle ages, namely monarchical government and the feudal system.

Without democracy, the demographic of Britain today would be entirely different. Some might argue that even without documents such as the Magna Carta, or events like the English Civil War, democracy would have inevitably emerged as the dominant political form.

This owes to movements such as the Enlightenment which represented a drastic shift in philosophical thought. It was at the time of the Enlightenment, for example, that the French Revolution took place. The monarchy was deposed and many in Britain felt its influences would spread.

One of the greatest influences of this age of enlightenment could be seen in the works of Thomas Paine, both Common Sense (1776) and The American Crisis (1776–1783), were two of the most influential pamphlets at the start of the American Revolution and helped inspire the Revolutionist in 1776 to declare independence from Great Britain. His ideas reflected Enlightenment-era ideals of transnational human rights.

Thomas Paine brought within his books many dangerous ideas to the oligarchy, for example, Rights of Man posits that popular political revolution is permissible when a government does not safeguard the natural rights of its people.

These ideas that the people should dare to uphold their rights even against the government have been part and parcel of our unspoken civil liberties since Magna Carta. It beggars’ belief that even today, parliament is still legislating to take away our rights to protest. You should ask on whose behalf they are acting, certainly not the people’s.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen was a written expression of the natural rights of citizens in revolutionary France. Inspired by British and American covenants, France’s declaration was the most ambitious attempt to protect individual rights in any European nation to that point. It would remain a cornerstone document of the revolution, motivating revolutionaries of all stripes and colours from then on.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen 1789, together with the 1215 Magna Carta, the 1689 English Bill of Rights, the 1776 United States Declaration of Independence, and the 1789 United States Bill of Rights, inspired in large part the 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The Representation of the People Act 1832 known as ‘The Great Reform Act’ was a “defining moment in the political history of Britain”. Despite excluding women, the Act increased the number of propertied men who could vote.

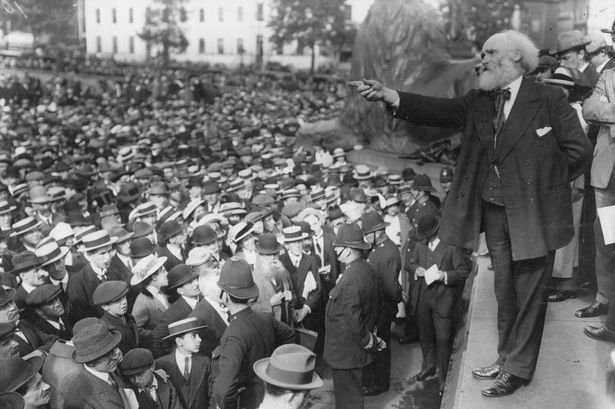

When the Act was introduced, there were huge demonstrations in support of reform with reports of a hundred thousand marching both in London and Birmingham. When the Lords blocked the Act there were serious riots in London, Bristol and Nottingham.

Fearing that British workers might follow the example of the French Revolution of July 1830, Parliament passed the Act in 1832. From its first stirrings, the struggle for democracy was intimately bound up with revolution, both real and feared.

By 1838 the campaign for democracy developed into the Chartist campaign for universal suffrage: “Chartism was the first instance of a political movement initiated and sustained by working people, relying on their own resources alone”.

When ‘The Great Reform Act’ passed confirming that women were officially excluded from voting. This became a defining moment in world history, the rights of man were for all mankind suffrage was to be universal.

Thousands of women were active in the Chartist movement. They organised over one hundred separate female Chartist associations between 1838 and 1849, some of which had thousands of members. Women signed the “monster petitions” presented to parliament, they were active at every level of the movement from writing articles to being key speakers at public meetings. Women were tenacious in their fight for democracy and their rights to vote in it. taking part in strikes and riots too. This was truly working-class unity fighting for emancipation and democracy.

Between 1881 and 1911 the employment of women workers grew by 24 percent, many in the “sweated” industries characterised by low pay, terrible conditions and excessive hours. There were very few women in trade unions outside of the cotton industry but women did play a leading role in militant struggles, for example, the West Yorkshire Woollen Weavers’ strike of 1875 and the all-important ‘Match Women’s Strike’ of 1888 in East London, These Eastend women showed that the most downtrodden of workforces could strike and win.

Organising women workers meant challenging prejudices. As socialist and suffrage campaigner Isabella Ford wrote: “All the orthodox religious world, broadly speaking, is against Trade Unionism for women because Trade Unionism means rebellion, and the orthodox teaching for women is submission in this world in order to gain happiness in the next”.

The Match Women’s Strike was a vital catalyst for ‘new unionism’. It was openly acknowledged by the dock strike leaders a year later in 1889 when the call went out from John Burns to a meeting of tens of thousands of strikers to:

“Stand shoulder-to-shoulder. with cries of “Remember the match women”, who won their fight and formed a union.”

The Match Women demonstrated to working people that it is possible for marginalised, unskilled workers to bind together in solidarity in trade unions and succeed in their demands for reasonable pay and conditions.

After the strike, it became when, rather than if the dockers would strike and ignite the modern Labour Movement, forming the roots of the Labour party. The suffragettes eventually, after the hardest of battles, women did get the vote though it took years of suffering before they won the right to vote.

This movement for working class emancipation now needed a manifesto of ideas.

Marxism.

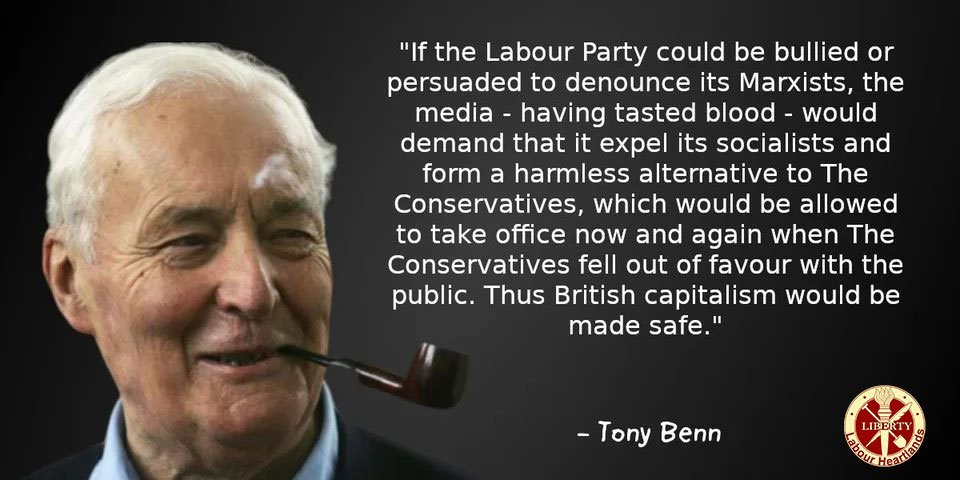

The best way of understanding the threat Marxism and its doctorings holds over the Oligarchy is to reproduce a part of Tony Benn’s address ‘Democracy and Marxism.’

“The term Marxist is used by the establishment to prevent it being understood. Even serious writers and broadcasters in the British media use the word Marxist as if it were synonymous with terrorism, violence, espionage, thought control, Russian imperialism and every act of bureaucracy attributable to the state machine in any country, including Britain, which has adopted even the mildest left of centre political or social reforms.

The effect of this is to isolate Britain from having an understanding of, or a real influence in, the rest of the world, where Marxism is seriously discussed and not drowned by propaganda, as it is in our so-called free press. This ideological insularity harms us all.

This continuing barrage of abuse is maintained at such a high level of intensity that it has obliterated — as is intended — any serious public debate in the mainstream media on what Marxism is about.

This negative propaganda is comparable to the treatment accorded to Christianity in non-Christian societies. Any sustained challenge to the existing order that cannot be answered on its merits is dismissed as coming from a Marxist, Communist, Trotskyite, or extremist.

All those suspected of Marxist views run the risk of being listed in police files, having their phones tapped and their career prospects stunted by blacklisting, just as those who advocate liberal ideas will be harassed in the USSR.

Those who openly declare their adherence to Marxism are pilloried as self-confessed Marxists, as if they had pleaded guilty to a serious crime and were held in custody awaiting trial.

Even the Labour Party, in which Marxist ideas have had a minority influence, is now described as a Marxist party, as if such a statement of itself put the party beyond the pale of civilised conduct, its arguments required no further answer, and its policies are entitled to no proper presentation to the public on the media.

One aspect of this propaganda assault which merits notice is that it is mainly waged by those who have never studied Marx, and do not understand what he was saying, or why, yet still regard themselves as highly educated because they have passed all the stages necessary to acquire a university degree.

For virtually the whole British establishment has been, at least until recently, educated without any real knowledge of Marxism, and is determined to see that these ideas do not reach the public. This constitutes a major weakness for the British people as a whole.

Six Reasons why Marxism is feared.

Why then is Marxism so widely abused? In seeking the answer to that question, we shall find the nature of the Marxist challenge in the capitalist democracies. The danger of Marxism is seen by the establishment to lie in the following characteristics.

First, Marxism is feared because it contains an analysis of an inherent, ineradicable conflict between capital and labour — the theory of the class struggle. Until this theory was first propounded the idea of social class was widely understood and openly discussed by the upper and middle classes, as in England until Victorian times and later.

But when Marx launched the idea of working-class solidarity, as a key to the mobilisation of the forces of social change and the inevitability of victory that that would secure, the term ‘class’ was conveniently dropped in favour of the idea of national unity around which there existed a supposed common interest in economic and social advance within our system of society, whether that common interest is real or not.

Anyone today who speaks of class in the context of politics runs the risk of ex-communication and outlawry. In short, they themselves become casualties in the class war which those who have fired on them claim does not exist.

Second, Marxism is feared because Marx’s analysis of capitalism led him to a study of the role of state power as offering a supportive structure of administration, justice and law enforcement which, far from being objective and impartial in its dealings with the people, was, he argued, in fact, an expression of the interests of the established order and the means by which it sustains itself.

One recent example of this was Lord Denning’s 1980 Dimbleby Lecture. It unintentionally confirmed that interpretation in respect of the judiciary and is interesting mainly because few 20th-century judges have been foolish enough to let that cat out of the bag, where it has been quietly hiding for so many years.

Third, Marxism is feared because it provides the trade union and labour movement with an analysis of society that inevitably arouses political consciousness, taking it beyond wage militancy within capitalism.

The impotence of much American trade unionism and the weakness of past non-political trade unionism in Britain have borne witness to the strength of the argument for a labour movement with a conscious political perspective that campaigns for the reshaping of society, and does not just compete with its own people for a larger part of a fixed share of money allocated as wages by those who own capital, and who continue to decide what that share will be.

Fourth, Marxism is feared because it is international in outlook, appeals widely to working people everywhere, and contains within its internationalism a potential that is strong enough to defeat imperialism, neo-colonialism and multinational business and finance, which have always organised internationally. But international capital has fended off the power of international labour by resorting to cynical appeals to nationalism by stirring up suspicion and hatred against outside enemies.

This fear of Marxism has been intensified since 1917 by the claim that all international Marxism stems from the Kremlin, whose interests all Marxists are alleged to serve slavishly, thus making them, according to capitalist establishment propaganda, the witting or unwitting agents of the national interest of the USSR.

Fifth, Marxism is feared because it is seen as a threat to the older organised religions, as expressed through their hierarchies and temporal power structures, and their close alliance with other manifestations of state and economic power.

The political establishments of the West, which for centuries have openly worshipped money and profit and ignored the fundamental teachings of Jesus do, in fact, sense in Marxism a moral challenge to their shallow and corrupted values and it makes them very uncomfortable.

Ritualised and mystical religious teachings, which offer advice to the rich to be good, and the poor to be patient, each seeking personal salvation in this world and eternal life in the next, are also liable to be unsuccessful in the face of such a strong moral challenge as socialism makes.

There have, over the centuries, always been some Christians who, remembering the teachings of Jesus, have espoused these ideas and today there are many radical Christians who have joined hands with working people in their struggles. The liberation theology of Latin America proves this and thus deepens the anxieties of church and state in the West.

Sixth, Marxism is feared in Britain precisely because it is believed by many in the establishment to be capable of winning consent for radical change through its influence in the trade union movement, and then in the election of socialist candidates through the ballot box.

It is indeed therefore because the establishment believes in the real possibility of an advance of Marxist ideas by fully democratic means that they have had to devote so much time and effort to the misrepresentation of Marxism as a philosophy of violence and destruction, to scare people away from listening to what Marxists have to say.

These six fears, which are both expressed and fanned by those who defend a particular social order, actually pinpoint the wide appeal of Marxism, its durability and its strength more accurately than many advocates of Marxism may appreciate.

Marxism and the Labour Party.

The Communist Manifesto, and many other works of Marxist philosophy, have always profoundly influenced the British labour movement and the British Labour Party, and have strengthened our understanding and enriched our thinking.

It would be as unthinkable to try to construct the Labour Party without Marx as it would be to establish university faculties of astronomy, anthropology or psychology without permitting the study of Copernicus, Darwin or Freud, and still expect such faculties to be taken seriously.

There is also a practical reason for emphasising this point now. The attacks upon the so-called hard Left of the Labour Party by its opponents in the Conservative, Liberal and Social Democratic Parties and by the establishment, are not motivated by fear of the influence of Marxists alone.

These attacks are really directed at all socialists and derive from the knowledge that democratic socialism in all its aspects does reflect the true interest of a majority of people in this country, and that what democratic socialists are saying is getting through to more and more people, despite the round-the-clock efforts of the media to fill the newspapers and the airwaves with a cacophony of distortion.

If the Labour Party could be bullied or persuaded to denounce its Marxists, the media having tasted blood would demand next that it expelled all its socialists and reunited the remaining Labour Party with the SDP to form a harmless alternative to the Conservatives, which could then be allowed to take office now and again when the Conservatives fell out of favour with the public.

Thus, British capitalism, it is argued, would be made safe forever, and socialism would be squeezed off the national agenda. But if such a strategy were to succeed — which it will not — it would in fact profoundly endanger British society. For it would open up the danger of a swing to the far right, as we have seen in Europe over the last 50 years.

This was an age that brought about many new ideas that threatened the Oligarchy, New men of this age of reason brought hope for the masses. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published many articles and books together that attempted to expose the uneven distribution of wealth gained during the Industrial Revolution.

Their writings see capitalism as an exploitative system that benefits the Oligarchy, the landowners through capital, and means of production more than the workforce. Simply put, they exposed the Oligarchy.

During the second half of the 20th century, social and political unrest changed the face of the western world, From the shock victory of Labour at the 1945 general election. The outcome of the 1945 election was more than a sensation. It was a political earthquake.

The voters wanted an end to wartime austerity and no return to prewar economic depression. They wanted change. Three years earlier, in the darkest days of the war, they had been offered a tantalising glimpse of how things could be in the bright dawn of victory.

The economist William Beveridge had synthesised the bravest visions of all important government departments into a single breathtaking view of the future.

The 1942 Beveridge Report spelt out a system of social insurance, covering every citizen regardless of income. It offered nothing less than a cradle-to-grave welfare state. People began to feel part of the system, politics was no longer something that happened to them, politics promised them they could be real stakeholders in society, their voice was beginning to be heard.

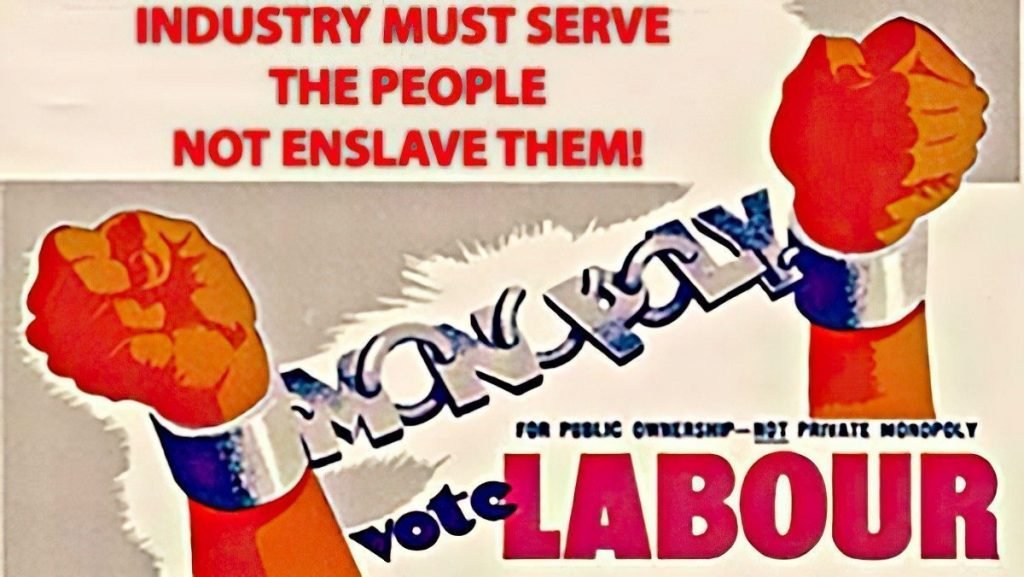

Socialism is a political and economic theory of social organisation that advocates that the means of production, distribution, and exchange should be owned or regulated by the community, the many. That’s a big chunk out of the pockets of the oligarchy, those few, that 1% who own everything.

It was the Industrial Revolution, and the emergence of modern trade unionism in the 19th century which provided a solid foundation of common interest upon which these Utopian dreams could be based, that gave the campaigns for political democracy and social advancement their first real chance of success.”

Did anyone really think the few would ever let go without a fight?

Socialism is terrifying to the oligarchy.

Benn also stated:” Karl Marx has to be seen as a great teacher who explained the world in a way that makes it possible to understand it. But the changes he believed necessary can only be brought about by democracy, which is the most revolutionary idea in the world. In Mein Kampf Hitler said, “democracy inevitably leads to Marxism.” Which is why he was against democracy.”

What’s obvious is that the very idea of socialism or any political ideology based on equality, democracy and liberty are to be demonised and attacked. Unfortunately, for the oligarchy, socialism was built into the very foundations of the Labour movement and the Labour movement had found through democracy and through the British democratic system democracy had a voice.

This stark sentence is buried in the party’s 1945 election manifesto, which promised that Labour would take control of the economy and in particular of the manufacturing industry stated defiantly:

“The Labour Party is a Socialist Party, and proud of it.”

The 1945 manifesto pledged the nationalisation of the Bank of England, the fuel and power industries, inland transport, and iron and steel. And with a majority of more than 150, the party could not be denied.

Labour’s promise to take over the commanding heights of the economy via nationalisation were dystopian to committed Tories, but after nearly six years of wartime state direction of the economy, it did not seem nearly so radical as it had before the war, in fact, the war had shown people that nationalisation had and could work.

And if industry was nationalised it was only a step away from common ownership, the Oligarchy would become very worried. But more so Great Britain and its last vestiges of imperialism still held court over much of the developing world, not to mention its more advanced economic commonwealth countries like Australia and Canada.

The wrong government could lose the Oligarchy’s vast fortunes, influence and dominance on the world stage.

The oligarchy is ever watchful, they guard their power and wealth jealousy. Their own statements declare socialism a cause for great concern. A more equal society would benefit the many but not the few.

A changing America.

The Civil Rights movement in America characterised and defined the age, another seismic swing to the people. Leaders emerged like Mexican American labour civil rights activist Cesar Chavez, who used the power of the electret system to make changes to workers’ rights, Chavez encouraged Mexican Americans to register and vote through his work with the Community Services Organisation, a Latino civil rights group.

In 1965, Mexican American civil rights activist César Chávez and the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) led California grape-pickers in a strike to demand higher wages. In 1966, Chávez and supporters marched from Delano to the state capital at Sacramento and called for Americans to boycott grapes in support of farmworkers.

The strike, which lasted five years, garnered national attention about the plight of the mostly Mexican migrant workers and their exploitation. The effort resulted in the first major labour victory for U.S. migrant workers.

In similar movements in South Texas in 1966, United Farm Workers—formerly NFWA—marched to Austin, Texas, in support of melon workers and UFW workers’ rights. In 1969, Chávez and UFW members protested growers’ use of illegal immigrants as strike-breakers by marching through the Imperial and Coachella Valley to the Mexican border.

The UFW organised strikes and boycotts in the early 1970s to get higher wages from grape and lettuce growers. Chávez led a boycott in the 1980s to protest toxic pesticide use on grapes. Chávez’ strike and boycott efforts resulted in signed bargaining agreements protecting farmworkers.

In the cities, militant civil rights leaders like Malcolm X, Huey Newton, Fred Hampton and their respective organisations motivated hundreds of thousands to demand equality. The Rainbow coalition actively worked to educate the poor working classes, the Rainbow coalition through the Black Panther movement had no race agenda,

it was an initiative to educate and feed the poor working classes. This was an education in understanding the struggle against capitalism and for socialism.

Martin Luther King jr. became an icon of the age making one of the most famous speeches in history. The iconic “I Have a Dream” speech was delivered during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963, in which he called for civil and economic rights and an end to racism in the United States.

On that same wave of populism, was John F. Kennedy, civil rights were the most contentious domestic issue of Kennedy’s presidency. Constrained by Southern Democrats in Congress who remained stridently opposed to civil rights for Black citizens, Kennedy offered only tepid support for civil rights reforms early in his term.

Near the end of 1963, in the wake of the March on Washington and while the speech “I have a dream” still echoed across America, Kennedy finally sent a civil rights bill to Congress. One of the last acts of his presidency and his life, Kennedy’s bill eventually passed as the landmark Civil Rights Act in 1964.

After years of activist lobbying in favour of comprehensive civil rights legislation, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was enacted in June 1964.

Though President John F. Kennedy had sent the civil rights bill to Congress in 1963, before the March on Washington, the bill had stalled in the Judiciary Committee due to the dilatory tactics of Southern segregationist senators such as James Eastland, a Democrat from Mississippi.

After the assassination of President Kennedy in November 1963, his successor, Lyndon Baines Johnson, gave top priority to the passage of the bill.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 contained provisions barring discrimination and segregation in education, public facilities, jobs, and housing. It created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to ensure fair hiring practices and established a federal Community Relations Service to assist local communities with civil rights issues.

The bill also authorised the US Office of Education to distribute financial aid to communities struggling to desegregate public schools.

After a coalition of religious groups, labour unions, and civil rights organisations mounted an intense grassroots effort to lobby support for the bill, the Senate finally passed it on June 11, by a vote of 73 to 27.

Though the Civil Rights Act of 1964 included provisions to strengthen the voting rights of African Americans in the South, these measures were relatively weak and did not prevent states and election officials from practices that effectively continued to deny southern blacks the vote.

Moreover, in their attempts to expand black voter registration, civil rights activists met with the fierce opposition and hostility of Southern white segregationists, many of whom were entrenched in positions of authority.

Civil rights activists marching from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, in March 1965. The vicious beatings and murders of civil rights workers after the passage of the Civil Rights Act radicalised some black activists, who became sceptical of nonviolent, integrationist tactics and began to adopt a more radical approach.

On March 7, 1965, six hundred activists set out on a march from Selma, Alabama to Montgomery to peacefully protest the continued violations of African Americans’ civil rights. When they reached the Edmund Pettus Bridge over the Alabama River, hundreds of deputies and state troopers attacked them with tear gas, nightsticks, and electric cattle prods.

The event, which the press dubbed “Bloody Sunday,” was broadcast over television and splashed across the front pages of newspapers and magazines, stunning and horrifying the American public.

Bloody Sunday galvanised civil rights activists, who converged on Selma to demand federal intervention and express solidarity with the marchers. President Johnson quickly became convinced that additional civil rights legislation was necessary.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965.

A week after Bloody Sunday, on March 15, 1965, President Johnson delivered a nationwide address in which he declared that “all Americans must have the privileges of citizenship regardless of race.”

Johnson informed the nation that he was sending a new voting rights bill to Congress, and he urged Congress to vote the bill into law. Congress complied, and President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 on August 6, 1965.

The bill outlawed poll taxes, literacy tests, and other practices that had effectively prevented southern blacks from voting.

It authorised the US attorney general to send federal officials to the South to register black voters in the event that local registrars did not comply with the law, and it also authorised the federal government to supervise elections in districts that had disfranchised African Americans.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 transformed patterns of political power in the South. By the middle of 1966, over half a million Southern blacks had registered to vote, and by 1968, almost four hundred black people had been elected to office.

Monarchies and empires were dissolving, while democracies were spreading around western Europe. For the Oligarchy to survive and maintain its status quo it would need to up its game and fight back.

The emancipation of the working class was gaining traction. There was a crisis of democracy, it was actually starting to work…

The modern Oligarchy and its agents.

The oligarchy has had many forms, sometimes it has maintained a high level of complexity and control, while at other times it has failed to control at all. Chartist, suffrage, and the growing emancipation of the working classes have managed to wrestle some amount of power from the elites, it’s not always been a one-sided battle as our modern struggle has shown.

The people have gained some small liberties and rights, giving power to democracy. However, in this age of instant information and technology, the Oligarchy has employed new tactics.

The age-old divide and conquer is the weapon of choice, under no account will the elites allow unity of the masses in a common struggle.

The Class war is sidelined, the people are caught up in IDPOL and culture wars where you are cancelled if you don’t use the right pronouns or give your 8 minutes of hate on demand.

Politicians taking sides on issues they have no experience with or know little about, like a celebrity endorsement they ride on waves of populism like surfers until they come crashing into the shore and nothing is resolved.

Constant cries of “24 hours to save the NHS” in a vein hope to stay relevant within a social media world of likes. The ‘shoulder to shoulder’ camaraderie is broken in a world of Atomisation.

The working classes, although more organised and stronger in many ways, are constantly under attack. The agencies used to represent the people are undermined from all sides.

Relentless media attacks have been used to undermine political parties, unions and movements. A constant tug of war is being waged, however, the one sure method of winning for the oligarchy is infiltration, ‘the enemy within,’ sent to undermine the democratic struggle and run interference throughout.

The iron law of oligarchy.

The iron law of oligarchy is a political theory first developed by the German-born Italian sociologist Robert Michels in his 1911 book, Political Parties. It asserts that rule by an elite, or oligarchy, is inevitable as an “iron law” within any democratic organisation as part of the “tactical and technical necessities” of the organisation.

Michels’s theory states that all complex organisations, regardless of how democratic they are when started, eventually develop into oligarchies. Michels observed that since no sufficiently large and complex organisation can function purely as a direct democracy, power within an organisation will always get delegated to individuals within that group, elected or otherwise.

Using anecdotes from political parties and trade unions struggling to operate democratically to build his argument in 1911, Michels addressed the application of this law to representative democracy, and stated:

“Who says organisation, says oligarchy.” He went on to state that “Historical evolution mocks all the prophylactic measures that have been adopted for the prevention of oligarchy.”

According to Michels, all organisations eventually come to be run by a “leadership class”, who often function as paid administrators, executives, spokespersons or political strategists for the organisation.

Far from being “servants of the masses”, Michels argues this “leadership class,” rather than the organisation’s membership, will inevitably grow to dominate the organisation’s power structures.

By controlling who has access to information, those in power can centralise their power successfully, often with little accountability, due to the apathy, indifference and non-participation most rank-and-file members have in relation to their organisation’s decision-making processes.

Michels argues that democratic attempts to hold leadership positions accountable are prone to fail, since with power comes the ability to reward loyalty, the ability to control information about the organisation, and the ability to control what procedures the organisation follows when making decisions.

All of these mechanisms can be used to strongly influence the outcome of any decisions made ‘democratically’ by members.

Michels stated that the official goal of representative democracy of eliminating elite rule was impossible, that representative democracy is a façade legitimising the rule of a particular elite, and that elite rule, which he refers to as oligarchy, is inevitable.

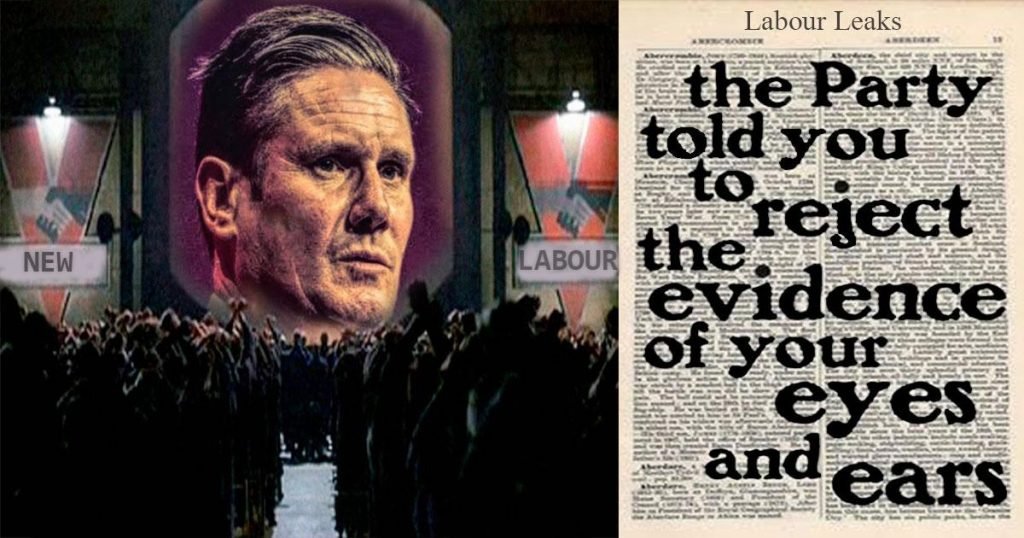

Nowhere can we see the Iron Law of Oligarchy in practice better than within the British Labour Party.

The Labour Party has allowed itself not only to be infiltrated but has allowed that cancerous growth to create its own network within the entire political organisation.

This infiltration has disenfranchised hundreds of thousands of members and even more voters.

The party machinery has been taken over creating a disconnect between members and the executive. The organisation soon became disjointed and weakened, membership has declined, apathy has taken over, with a “what’s the point” attitude that has crashed its grassroots support.

It’s ironic, political parties have always recognised the act of entryism, the Labour Party have always guarded against Trotskyites entering from the Left, however, it was the right of the party that let the drawbridge down.

The consequence of this happens when the very top of a party has been compromised.

If anyone doubts this Iron Law of oligarchy just look at how deeply compromised the Labour Party has become, you only have to read the suppressed Labour Leaks.

That damning report openly states the Labour Staffers involved had a strong crossover from Lord Peter Mandelson’s group, “Britain Stronger IN For Europe,” an EU referendum Remain organisation and forerunner to Mandelson’s ‘Peoples vote’ campaign.

It may also just be a coincidence that both the Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer and his right-hand man Lord Peter Mandelson can both add to their titles, ‘Trilateralist’. Both belong to the Trilateral commission an organisation that believes democracy is for the elite, while people are to be managed nothing more.

We can also speculate on the involvement of these two ‘Trilateralist’ and the extent of their involvement in the Labour Leaks, one with deep connections to the Labour staffers involved in what appears to be a concerted effort to bring down Jeremy Corbyn and the Labour Party. The other in suppressing the Forde inquiry from becoming public.

The consequence of which is what happens when the very top of a party has been compromised.

Both its leader Sir Keir Starmer and frontbench right-hand man Lord Peter Mandelson can both add to their titles ‘Trilateralist’. Both are members of an organisation that believes democracy is for the elite, while people are to be managed nothing more.

The Oligarchy will not relinquish control, our rights were never given, we had to win them.

For over 300 years the working class have exerted their rights, we had fought and won, we no longer doffed our caps or bowed our heads, suffrage had given the working classes legitimacy.

The Oligarchy had recognised the threat to its power, it understood the crisis, that crisis was democracy itself and to combat that threat it would need to organise.

David Rockefeller, an oligarch to his bones, looked around at the changing face of the world, he witnessed the growing civil rights movements and the growing demands around the world for equality and justice.

The take-up of socialism by the masses was a threat to the status quo.

The scales of power had shifted to the people, this demand for equality, voting rights and democracy brought a very real existential threat to all the Oligarchy hold dear, their power, wealth and influence.

it was under that threat of real democracy and the growing civil rights movement that the Oligarchy reacted, they created the Trilateral Commission.

The coming of the Trilateral Commission.

The Trilateral Commission was founded at the initiative of David Rockefeller in 1973. Its members are drawn from the three components of the world of capitalist democracy: the United States, Western Europe, and Japan.

Among them are the heads of major corporations and banks, partners in corporate law firms, Senators, Professors of international affairs — the familiar mix in extra-governmental groupings. Along with the 1940s project of the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), directed by a committed “Trilateralist” and with numerous links to the Commission, the project constituted the first major effort at global planning since the War Peace Studies program of the CFR during World War II.

According to David Rockefeller, the “impact of growing economic competitiveness and the accelerating pace of technological and social change on policymaking in major industrialised states” had made it imperative that governments transcended the “issues of the moment” and devoted themselves to the strategic problems of the future.

“Now,” he declared, “is a propitious time for persons from the private sector to make a valuable contribution to public policy.”

Who are the Trilateral Commission?

On paper, the Trilateral Commission is an organisation of private citizens founded to confront challenges posed by the growing interdependence of the United States and its principal allies (Canada, Japan, and the countries of western Europe) and to encourage greater cooperation between them.

The Trilateral Commission is headed by three regional chairs (for Europe, North America, and the Asia-Pacific region), who are assisted by several deputies, and an executive committee. The entire membership meets annually (the location rotating among the three regions) to consider reports and debate strategy. Regional and national meetings are held throughout the year. Regional headquarters are in Paris, Washington, D.C., and Tokyo.

The Trilateral Commission’s principles of representation are economic weight and political influence and are reflected in the varying membership quotas assigned to each country. The Trilateral Commission reflects powerful commercial and political interests committed to private enterprise and stronger collective management of global problems.

Its members (more than 400 in the early 21st century) are influential politicians; banking and business executives; media, civic, and intellectual leaders; and a few trade union chiefs. Membership is by invitation only.

The Commission claims it drew together ‘the highest-level unofficial group possible’ so as ‘to foster closer cooperation among these core democratic industrialised areas of the world with shared leadership responsibilities in the wider international system’. Originally members were from Japan, Europe and North America but it has since widened its membership to include Chinese, Indian, Mexican and Asian members.

The Trilateral Commission has been funded by David Rockefeller, the Charles F. Kettering Foundation, and the Ford Foundation. Although members hold high-level positions in business and academia or have held such positions in government, they attend meetings as private individuals and therefore are free from the constraints of having to represent their organisations.

Membership is by invite only. That membership has included Presidents, Prime ministers, EU commissioners and Bankers. The Trilateral Commission has also had some extremely controversial members such as the convicted sex offender Jeffery Epstein, however, we will look closer at the membership after we understand more about this self-proclaimed guardian of neoliberalism.

Criticism of the Trilateral Commission.

The commission has garnered much controversy over its existence. Detractors cite the levels of influence some commission members wield in politics and their associations with government entities as reasons to question the commission’s activities. Critics say this influence helps the commission prop up the world’s financial and political elite rather than the best interests of the general public.

Holly Sklar in her book on Trilateralism, says the purpose of Trilateralism is to protect the power of the international ruling class “whose locus of power is the global corporation”; to co-opt the Third World, and to reintegrate communist countries.

The Commission’s purpose is to engineer an enduring partnership among the ruling classes of North America, Western Europe, and Japan—hence the term “trilateral”—in order to safeguard the interests of Western capitalism in an explosive world.

Noam Chomsky says the Trilateral commission’s aim is to bring about a ‘moderation in democracy’ to allow only the elite to vote. No matter where your politics sit, this is a backwards step in democracy and the working class movement for emancipation.

This is the elites advocating a shareholder society, where those with the biggest share in society are in their eyes the ones with the most to lose in terms of wealth, land and power and that is why they should be the only ones to have a say in our society. This is a return to a feudal system worldwide controlled by the Trilateral Commission.

The Crisis of Democracy: On the Governability of Democracies.

The social critic and academic Chomsky criticised the commission declaring its aims ‘undemocratic’, pointing to its publication ‘The Crisis of Democracy, which describes strong popular interest in politics during the 1970s as an “excess of democracy”.

In layman’s terms the civil rights movement, the unions in the UK and the up and coming democratic movements around the world were dangerous to globalisation, corporations and the oligarchy.

The Trilateral Commission has issued one major book-length report, namely, The Crisis of Democracy: On the Governability of Democracies (Michel Crozier, Samuel Huntington, and Joji Watanuki, 1975). The Commission’s report is concerned with the “governability of the democracies.”

This report sits on the website of the Trilateral Commission as its only manifesto, a report that in a nutshell says the problem with the world is too much democracy.

The report argues that what is needed in the industrial democracies “is a greater degree of moderation in democracy” to overcome the “excess of democracy” of the past decade. “The effective operation of a democratic political system usually requires some measure of apathy and non-involvement on the part of some individuals and groups.”

Chomsky described it as one of the most interesting and insightful books showing the modern democratic system not to really be a democracy at all, but controlled by elites, the oligarchy.

The report observed the political state of the United States, Europe and Japan, and says that in the United States the problems of governance “stem from an excess of democracy” and thus advocates “to restore the prestige and authority of central government institutions.” The report serves as an important point of reference for studies focusing on the contemporary crisis of democracies.

It is widely and correctly observed that the international system established after World War II had been significantly damaged by the mid-1970s.

The Trilateral Commission Report on the “Crisis of Democracy” defines this international system simply and accurately. “For a quarter-century, the United States was the hegemonic power in a system of world order,” the system that arose from the ashes of World War II, which of course left the United States in a position of overwhelming power, sufficient to materially influence historical developments though not to control them completely in its interests.

Excerpted from Radical Priorities, 1981 by Noam Chomsky.

In this collective management, the United States will continue to play ‘the decisive role. As Kissinger has explained, other powers have only “regional interests” while the United States must be “concerned more with the overall framework of order than with the management of every regional enterprise.” If a popular movement in the Arabian Peninsula is to be crushed, better to dispatch US-supplied Iranian forces, as in Dhofar.

If passage for American nuclear submarines must be guaranteed in Southeast Asian waters, then the task of crushing the independence movement in the former Portuguese colony of East Timor should be entrusted to the Indonesian army rather than an American expeditionary force. The massacre of over 60,000 people in a single year will arouse no irrational passions at home and American resources will not be drained, as in Vietnam.

If a Katangese secessionist movement is to be suppressed in Zaire (a movement that may have Angolan support in response to the American-backed intervention in Angola from Zaire, as the former CIA station chief in Angola has recently revealed in his letter of resignation), then the task should be assigned to Moroccan satellites forces and to the French, with the US discreetly in the background.

If there is a danger of socialism in southern Europe, the German proconsulate can exercise its “regional interests.” But the Board of Directors will sit in Washington….

A system run by the Oligarchy through the Trilateral Commission will create a new world order.

Modern feudalism, debt slaves owned by the company, their subscribed viewers.

Let’s not be mistaken. This was a group of the most powerful wealthy and influential middle-aged men of their generation coming together to bring in a new world order based on their ideals of economics, globalisation, distribution, society structure and democracy. They are not doing this to extend democracy and our civil liberties. This group of people advocate through their own doctoring’s that democracy should be managed, for the few and not the many. They are the agents of the oligarchy.

As Huntington observes, “Truman had been able to govern the country with the cooperation of a relatively small number of Wall Street lawyers and bankers,” a rare acknowledgement of the realities of political power in the United States.

But by the mid-1960s this was no longer possible since “the sources of power in society had diversified tremendously,” the “most notable new source of power” being the media. In reality, the national media have been properly subservient to the state propaganda system, a fact on which I have already commented.

Huntington’s paranoia about the media is, however, widely shared among ideologists who fear a deterioration of American global hegemony and an end to the submissiveness of the domestic population.

A second threat to the governability of democracy is posed by the “previously passive or unorganised groups in the population,” such as “blacks, Indians, Chicanos, white ethnic groups, students and women — all of whom became organised and mobilised in new ways to achieve what they considered to be their appropriate share of the action and of the rewards.”

The threat derives from the principle, already noted, that “some measure of apathy and non-involvement on the part of some individuals and groups” is a prerequisite for democracy.

Anyone with the slightest understanding of American society can supply a hidden premise: the “Wall Street lawyers and bankers” (and their cohorts) do not intend to exercise “more self-restraint.” We may conclude that the “greater degree of moderation in democracy” will have to be practised by the “newly mobilised strata.”

Huntington’s perception of the “concerted efforts” of these strata “establish their claims” and the “control over… institutions” that resulted is no less exaggerated than his fantasies about the media. In fact, the Wall Street lawyers, bankers, etc., are no less in control of the government than in the Truman period, as a look at the new Administration or its predecessors reveals.

But one must understand the curious notion of “democratic participation” that animates the Trilateral Commission study.

Its vision of “democracy” is reminiscent of the feudal system. On the one hand, we have the King and Princes (the government). On the other, the commoners. The commoners may petition, and the nobility must respond to maintain order.

There must however be a proper “balance between power and liberty, authority and democracy, government and society.” “Excess swings may produce either too much government or too little authority.”

In the 1960s, Huntington maintains, the balance shifted too far to society and against government. “Democracy will have a longer life if it has a more balanced existence,” that is, if the peasants cease their clamour.

Real participation of “society” in government is nowhere discussed, nor can there be any question of democratic control of the basic economic institutions that determine the character of social life while dominating the state as well, by virtue of their overwhelming power. Once again, human rights do not exist in this domain.

The report does briefly discuss “proposals for industrial democracy modelled on patterns of political democracy,” but only to dismiss them.

These ideas are seen as “running against the industrial culture and the constraints of business organisation.” Such a device as German co-determination would “raise impossible problems in many Western democracies, either because leftist trade unionists would oppose it and utilise it without becoming any more moderate, or because employers would manage to defeat its purposes.”

In fact, steps towards worker participation in management going well beyond the German system are being discussed and in part implemented in Western Europe, though they fall far short of true industrial democracy and self-management in the sense advocated by the libertarian left.

They have evoked much concern in business circles in Europe and particularly in the United States, which has so far been isolated from these currents, since American multinational enterprises will be affected. But these developments are anathema to the Trilateralist study.

Still another threat to democracy in the eyes of the Commission study is posed by:

“The intellectuals and related groups who assert their disgust with the corruption, materialism, and inefficiency of democracy and with the subservience of democratic government to ‘monopoly capitalism’”

(The latter phrase is in quotes since it is regarded as improper to use an accurate descriptive term to refer to the existing social and economic system; this avoidance of the taboo term is in conformity with the dictates of the state religion, which scorns and fears any such sacrilege).

Intellectuals come in two varieties, according to the trilateral analysis. The “technocratic and policy-oriented intellectuals” are to be admired for their unquestioning obedience to power and their services in social management, while the “value-oriented intellectuals” must be despised and feared for the serious challenge they pose to democratic government, by “unmasking and delegitimization of established institutions.”

The authors do not claim that what the value-oriented intellectuals write and say is false. Such categories as “truth” and “honesty” do not fall within the province of the apparatchiks.

The point is that their work of “unmasking and delegitimization” is a threat to democracy when popular participation in politics is causing “a breakdown of traditional means of social control.” They “challenge the existing structures of authority” and even the effectiveness of “those institutions which have played the major role in the indoctrination of the young.” Along with “privatistic youth” who challenge the work ethic in its traditional form, they endanger democracy, whether or not their critique is well-founded. No student of modern history will fail to recognise this voice.

What must be done to counter the media and the intellectuals, who, by exposing some ugly facts, contribute to the dangerous “shift in the institutional balance between government and opposition”?

How do we control the “more politically active citizenry” who convert democratic politics into “more an arena for the assertion of conflicting interests than a process for the building of common purposes”? How do we return to the good old days when “Truman, Acheson, Forrestal, Marshall, Harriman, and Lovett” could unite on a policy of global intervention and domestic militarism as our “common purpose,” with no interference from the undisciplined rabble?

The crucial task is “to restore the prestige and authority of central government institutions, and to grapple with the immediate economic challenges.”

The demands on government must be reduced and we must “restore a more equitable relationship between government authority and popular control.”

The press must be reined in. If the media do not enforce “standards of professionalism,” then “the alternative could well be regulation by the government” — a distinction without a difference, since the policy-oriented and technocratic intellectuals, the commissars themselves, are the ones who will fix these standards and determine how well they are respected.

Higher education should be related “to economic and political goals,” and if it is offered to the masses, “a program is then necessary to lower the job expectations of those who receive a college education.” No challenge to capitalist institutions can be considered, but measures should be taken to improve working conditions and work organisation so that workers will not resort to “irresponsible blackmailing tactics.” In general, the prerogatives of the nobility must be restored, and the peasants controlled and apathy that becomes them.

This is the ideology of the liberal wing of the state-capitalist ruling elite, and, it is reasonable to assume, its members who now staff high ranking positions all over the world. Able to call meetings with Bankers prime ministers and presidents.

The political system can usefully be characterised as oligarchic. We can argue that oligarchy is not inconsistent with democracy; that oligarchs need not occupy formal office or conspire together or even engage extensively in politics in order to prevail; that great wealth can provide both the resources and the motivation to exert potent political influence.

These men are the oligarchy of today; they work to maintain their power, influence and wealth against all comers, including governments and the people they are supposed to represent within their given democracies.

The commission was clear in its intentions, from their perspective the world needed order. The three regions of the Trilateral had to work together for the good of all, or a better phrase would be for their own good, especially their own personal vastly expanding commercial concerns.

The age of Corporate Globalisation had been interrupted twice in the 20th century through the major conflicts of both World wars, their aim is a new world order, one that does not disrupt their power or wealth. To do that they must manage the governments and the people and in doing so create the illusion of democracy.

This recommendation recalls the analysis of Third World problems put forth by other political thinkers of the same persuasion, for example, Ithiel Pool (then chairman of the Department of Political Science at MIT), who explained some years ago that in Vietnam, the Congo, and the Dominican Republic, “order depends on somehow compelling newly mobilised strata to return to a measure of passivity and defeatism…

At least temporarily the maintenance of order requires a lowering of newly acquired aspirations and levels of political activity.” The Trilateral recommendations for the capitalist democracies are an application at home of the theories of “order” developed for subject societies of the Third World.

The problems affect all of the trilateral countries, but most significantly, the United States. As Huntington points out, “for a quarter-century the United States was the hegemonic power in a system of world order” — the Grand Area of the CFR [Council on Foreign Relations]. “A decline in the governability of democracy at home means a decline in the influence of democracy abroad.” He does not elaborate on what this “influence” has been in practice, but ample testimony can be provided by survivors in Asia and Latin America.

Third world tactics can always be transferred to first world problems.

The report states what is needed in the industrial democracies “is a greater degree of moderation in democracy” to overcome the “excess of democracy” of the past decade. “The effective operation of a democratic political system usually requires some measure of apathy and non-involvement on the part of some individuals and groups.”

What we do understand is that the oligarchy and in particular their agents are prepared to smash any attempt at real democracy.

In present circumstances, the tactic of apathy being employed amongst socialists within the UK. It seems Jeremy Corbyn’s promise of extending democracy to the people has created an acute case of too much hope and that illusion needs shattering.

Sir Keir Starmer Trilateralist and Leader of the Labour Party.

Out of chaos, the Oligarchy will bring order.

The current leader of the opposition Labour Party in the UK, Sir Keir Starmer, is an active member of the Trilateral commission according to the June 2020 membership roster. This is a fact that is not mentioned on Starmer’s own website, his official parliamentary web page or in the national media.

When he was campaigning to be Labour leader in February 2020, Starmer’s connection to the Commission was kept suppressed, only small media outlets and blogs touched on his membership. During the leadership contest in mid-February Sir Keir Starmer’s campaign team was forced to deny that they had illegally accessed Labour party membership data.

The matter was raised on a live BBC leadership debate show hosted by Victoria Derbyshire, where one member of the studio audience suggested that the reason Starmer was not facing an official investigation was because of his membership of the Trilateral Commission. Starmer very quickly brushed off the claim, and Derbyshire just as quickly moved on to another member of the audience.

This was an ideal opportunity to question Starmer on his involvement in the Commission – to ask what it is and how it may or may not influence his political beliefs and motivations. Instead, the BBC chose to ignore the issue.

They say you cannot serve two masters, the fact that the Trilateral Commission is an organisation dedicated to the pursuit of neoliberalism should be questioned.

Lively discussion this morning @ Trilateral Commission. Different points of view is an understatement: different visions for Britain! https://t.co/4kVl9HIDbv

— Keir Starmer (@Keir_Starmer) November 4, 2017

What is this fantastic vision Starmer speaks about?

The Trilateral Commission is a totalitarian entity that would like Britain to become a one-party Tory state. Starmer is paving the way for Boris Johnson to do his worst? Every day he and fellow Trilateral Commission member Lord Peter Mandelson make decisions for Labour, the party is not just dying, Starmer is killing it.

Sir Keir Starmer may be in opposition, but his membership is relevant because the Commission is informing debate and is seeking to influence national administrations to adopt globally devised initiatives. Starmer is part of that process.

And it should be stressed again – out of 650 members of parliament, Starmer is the only one who was invited into the Commission (membership is by invitation only). Perhaps this is because of his legal prowess, as from 2008 to 2013 he was the Director of Public Prosecutions, the third most senior prosecutor for England and Wales.

Like most elite organisations that work within a shadow world, from the Bilderbergs to the Masons, we could speculate on the many conspiracies surrounding the Trilateral commission and there are plenty to go at.

The fact that there are conspiracies surrounding them and are often quite outlandish also gives the Trilateral commission cover to carry out their agendas to control and manage society, if you brief against them by default you become a conspiracist, it’s a very clever catch-all.

These self-proclaimed masters of our social-economic world have only one ambition, to manage society in their quest for globalisation and retention of their personal power and wealth.

At this point, a fair question to ask is what authority does the Trilateral Commission possess that allows them to believe that they could bypass national governments in pursuit of global objectives? After all, this is a commission that is not elected but has within its ranks men and women who are elected at the national level.

It is a commission that is dominated by corporate interests and is privately funded. Trilateral Commission members act as agents of the Oligarchy and in their interest alone.

The quest for globalisation and the freedom of movement of goods and services in an undisturbed flow of their wealth and power gives them great influence. The Trilatrilist have a virtual open door into the EU commission, they meet as often, if not more than heads of EU countries. A list of meetings can be seen on their website.

It’s not just the former EU commissioner and Blairite Lord Mandelson either.

The connections run deep and some of their members stand out more than others. It is quite telling from the list of members how far their influence runs. Lord Kerr of Kinlochard for instance, the man that wrote the heavily bias article 50 that works to keep member states tied to the EU is a Trilatriist.

After a high-flying career in the Foreign Office that included assignments as Britain’s ambassador to Washington and to the EU, Kerr drew up the text as secretary-general of the European Convention, which was charged with writing the constitutional treaty in 2002 and 2003.

Kerr used Article 50 to tie member states to the EU in his own words he claimed:

“It seemed to me very likely that a dictatorial regime would then, in high dudgeon, want to storm out” — Lord Kerr

However, what we found was that even after a democratic vote and the British parliament invoking Article 50 it was near-on-impossible to leave the EU, in doing so it brought parliament to its knees, however a landslide victory based on three words ‘get Brexit done’ gave the UK little choice but to uphold the democratic choice of the people, despite the best efforts from the Trilatriist.

Other members of the Trilateral commission are packed into that other undemocratic institute The House of Lords. The list of former and present members gives some indication of their political stance.

An example of the connection to globalization and free markets includes Christopher Francis Patten, Baron Patten of Barnes, the 28th and last Governor of Hong Kong from 1992 to 1997 and Chairman of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1992.

He was made a life peer in 2005 and has been Chancellor of the University of Oxford since 2003. He was European Commissioner for External Relations from 1999 to 2004 and Chairman of the BBC Trust from 2011 to 2014.

Sir Arthur Nicholas Winston Soames, British Conservative Party politician who served as the Member of Parliament and grandson of former prime minister Sir Winston Churchill.

Stephen Gilbert, Baron Gilbert of Panteg, he served as Deputy Chairman of the Conservative Party until 2015. He decided to step down in November 2016, when he took up a part-time position at Populus, the official polling company for the main campaign to keep Britain in the EU.

Lady Barbara Judge, Chairman, Astana Financial Services Authority; Chairman, Cifas, the UK fraud prevention agency, former Chairman, UK Pension Protection Fund, London; former Chairman, UKAEA (United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority); former US Securities Exchange Commissioner.

The recently deceased Leon Brittan, Baron Brittan of Spennithorne, another British Conservative politician and barrister who served as a European Commissioner.

David Miliband, President and Chief Executive Officer, International Rescue Committee, New York; former Member of the British Parliament; former Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, London