Two former paratroopers accused of the murder of an Official IRA leader have been formally acquitted after prosecutors offered no further evidence at their trial.

The veterans’ trial at Belfast Crown Court collapsed after the Public Prosecution Service confirmed it would not appeal against a decision by Mr Justice O’Hara to exclude statements given by the ex-soldiers about the shooting of Joe McCann in 1972.

It was the first trial in several years that involved charges against former military personnel who served in the Northern Ireland conflict.

Four other cases involving the prosecution of veterans are at the pre-trial stage in the region’s courts.

Joe McCann, 24, was shot dead by paratroopers as he attempted to evade arrest by a plain-clothed police officer in the Markets Area of Belfast in April 1972.

The court heard he was evading arrest when soldiers opened fire, killing him.

Soldiers A and C, both in their 70s, had pleaded not guilty. The men admitted firing shots but said they had acted lawfully when doing so.

Both soldiers were interviewed by a police legacy unit, the Historical Enquiries Team (HET), in 2010 and it was this evidence that formed a substantial part of the prosecution’s case.

The judge ruled this evidence as inadmissible and the Public Prosecution Service (PPS) on Tuesday confirmed it would not appeal against that decision, meaning the case could not proceed.

Not guilty of the charge of murder

After the prosecution confirmed it would be presenting no further evidence in the case, the judge told both former soldiers: “In the circumstances, Mr A and C, I formally find you not guilty of the charge of murder.”

Mr Justice O’ Hara said during a discrete hearing on the admissibility issue: ‘One of the remarkable features of the case is after the HET interviews they weren’t interviewed by the PSNI, they weren’t arrested, but they are in court on trial for murder.’

Philip Barden, the senior partner at Devonshires solicitors who represented soldiers A and C, said the firm made legal submissions back in 2016 making clear that the evidence from their clients would not be admissible.

“The stress of these proceedings on the soldiers and their families cannot be underestimated,” he said.

“This is a prosecution that should never have got off the ground. Before initiating the prosecution, the PPS had all the relevant information to conclude that the evidence was clearly inadmissible. Despite this, the prosecution proceeded.”

He added: “I call for an inquiry by a senior judge to investigate the decision-making process and to ensure that the decision to prosecute these veterans was not political.”

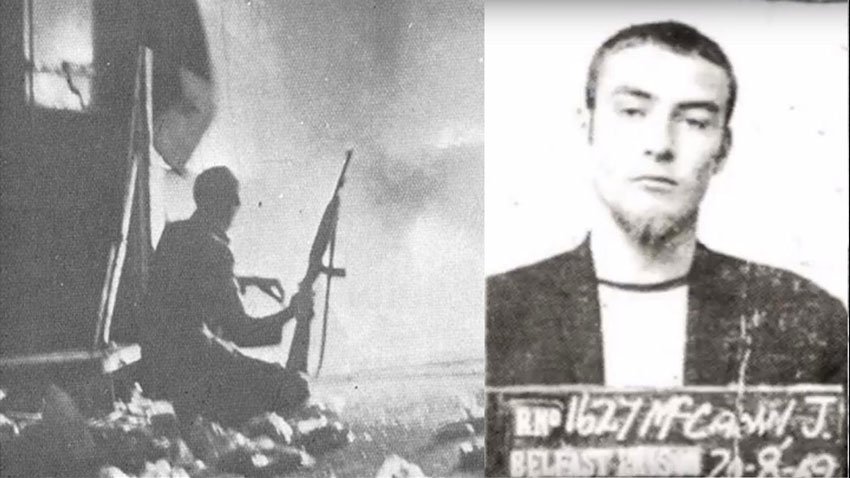

Joe McCann became recruitment poster of the IRA

The Official IRA leader was a republican legend even before his killing for organising the “Battle of Inglis’ Bakery” in the Market district of Belfast on 9 August 1971. Nine months later, McCann was shot dead by troops in the same area.

Pictured wielding a gun on a Belfast street, McCann is the subject of one of the most iconic images of the Northern Ireland troubles. T photograph showing him crouched with a gun in the burning building made him a nationalist pin-up. Some have suggested the cover for U2’s 1983 album Under A Blood Red Sky was inspired by the picture.

McCann’s death, nine weeks after Bloody Sunday, sparked five days of rioting. And in a series of brutal acts of revenge, the IRA shot five British soldiers, killing three.

A report into the death by the Historic Allegations Team concluded McCann was regarded by security forces as a “dangerous terrorist and someone who would not hesitate to use his weapon to resist arrest”.

A few days after the shooting McCann’s body was returned to the family home in Turf Lodge, where it was left to lie in state.

The funeral was one of the biggest in Belfast with a procession of more than 2,000 following the tricolour-draped coffin, led by a lone piper and McCann’s Irish Wolfhound. Around 20,000 lined the route. A memorial to him at the site of his death lauds him as an IRA captain. McCann was born in the Lower Falls area and joined the Republican movement while a teenager.

By 20 he had been jailed for possessing weapons. In August 1969 he helped to organise riots in Divis Street, which raged for two days with petrol bombs thrown and gunfire exchanged, resulting in several deaths.

IRA commander ‘had killed 15 British soldiers by the time he was shot dead’, court told

Belfast Crown Court heard the prominent member of the old Official IRA had been responsible for the deaths of 15 British soldiers in Northern Ireland.

His widow Anne and their family had waited nearly 49 years for their day in court, only to see the trial collapse in a week.

His family have said they will apply to the Attorney General to open an inquest into his killing.

Speaking outside the court, the McCann family’s lawyer Niall Murphy said: “This ruling does not acquit the state of murder. This ruling does not mean that Joe McCann was not murdered by the British Army.

“This trial has heard very clear evidence that Joe McCann was murdered by the British Army. He was shot in the back whilst unarmed from a distance of 40m posing no threat. It was easier to arrest him than to murder him.

“He was murdered because the British Army operated with impunity for their crimes.”

He said that there was “no doubt” that the soldiers did shoot McCann and said it was not the end of the family’s demand for justice.

“They will now apply to the current Attorney General to open the inquest at which Soldiers A and C will be compelled to appear and give evidence and be cross-examined,” he said.

1972 evidence ‘dressed up with 2010 cover’

The trial opened last Monday and heard a day of evidence before moving to the issue of whether statements and interviews given by the ex-soldiers would be admissible.

The court was told that evidence implicating the soldiers came from two sources – statements given to the Royal Military Police in 1972 and interview answers given to the HET in 2010.

The PPS accepted that the 1972 statements would be inadmissible in isolation, due to deficiencies in how they were taken including that the soldiers were ordered to make them and they were not conducted under caution.

However, prosecutors argued that the information in the 1972 statements became admissible because they were adopted and accepted by the defendants during their engagement with the HET in March 2010.

However, the judge said it was not legitimate to put the 1972 evidence before the court “dressed up and freshened up with a new 2010 cover”.

He questioned why the HET’s re-examination did not prompt a fresh investigation by the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), with the veterans interviewed under caution.

The judge suggested that course of action might have made a prosecution more sustainable.

“Under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement, veterans are being left open to prosecution while terrorists have been cleansed of their past crimes.

‘Live the rest of their lives in peace’

Former Veterans Minister Johnny Mercer, who left the government in April over legal protections for troops who served during the Troubles in Northern Ireland, attended the trial.

Speaking after it collapsed, he said he was “delighted” for the former soldiers, adding he hoped they could “go and live the rest of their lives in peace”.

“The government has made very clear promises, and the prime minister has made very clear promises, on legislation to end the relentless pursuit of those who served their country in Northern Ireland,” he said.

“It is time to deliver on that.”

Four other cases in relation to Army veterans are currently before the courts.

Operation Banner in Northern Ireland was the longest continuous deployment of Armed Forces personnel in British military history and involved over 250,000 military personnel.

Between August 1969 and July 2007 1,441 military personnel died as a result of operations in Northern Ireland. 722 of those personnel were killed in paramilitary attacks.

During the same period the British military were responsible for the deaths of 301 individuals, over half of whom were civilians.

In total, around 3,520 individuals lost their lives during the Troubles.

Military law and the rules of engagement

Military personnel are, at all times, subject to both Service law and civilian law, wherever they are serving in the world. As such, Armed Forces personnel are not immune from prosecution for offences committed whilst serving.

For every military operation personnel are issued with a specific set of Rules of Engagement which establish the circumstances and limitations under which personnel can use armed force. They are operation, not Service, specific and are intended to help commanders and soldiers to operate within the law or any political restraints under which they may be operating. They do not, however, have any legal force.

The Rules of Engagement for personnel serving in Northern Ireland were contained in what was commonly referred to as ‘The Yellow Card’. The original version of the Card, which extended to 21 distinct rules, was considered too detailed and complex, and was subsequently amended in 1980 to contain just 6 rules. Among them was the directive that only the minimum force necessary was to be used and that firearms should only be used as a last resort. The Card was amended again in 1994, following a court judgement in the case of Private Lee Clegg the previous year.

Prosecutions of Armed Forces personnel during the Troubles

Any fatalities involving the Armed Forces were investigated by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) at the time and, in some cases, prosecutions were brought against military personnel.

In most cases those fatalities were a direct result of operations and “centred around the key issue of whether the soldier had the right to open fire in the particular circumstances pertaining at the time”. This resulted in a number of convictions, although in the majority of cases the Director of Public Prosecutions for Northern Ireland directed that there was no case to answer, or the defendants were acquitted at trial.

Good Friday Agreement and “On the Runs”

The 1998 Good Friday Agreement made no provision for the investigation or prosecution of former members of the Armed Forces, focusing instead upon the early release of prisoners affiliated to paramilitary organisations. There was no amnesty for crimes which had not yet been prosecuted.

From 2000 to 2014, the UK Government operated an administrative scheme by which individuals suspected of terrorism crimes in Northern Ireland could find out whether they were at risk of arrest or prosecution if they returned to the UK. The collapse of a trial in 2014 led to a judge-led review. The report of that review criticised the scheme for systematic failings, but emphasised that it did not constitute an amnesty or immunity from prosecution.

Investigation of deaths related to the Troubles

In 2006 the Historical Enquiries Team (HET) was set up by the Government as part of the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) in response to judgements at the European Court of Human Rights related to the investigation of deaths in which State involvement was alleged. Those judgements found various shortcomings which amounted to breaches of Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights relating to the protection, by law, of the right to life.

The role of the HET was to examine all deaths attributable to the security situation that occurred in Northern Ireland between 1968 and the Belfast Agreement in 1998.

The HET looked into cases on a chronological basis, with some exceptions: previously opened investigations, those with humanitarian considerations, investigations involving issues of serious public interest and linked series of murders.

In 2012 the Minister of Justice for Northern Ireland commissioned Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) to inspect the role and function of the Historical Enquiries Team. The inspection focused on whether the HET’s approach to reviewing cases involving the security forces conformed to current policing standards and policy; if it adopted a consistent approach to all cases and if the HET’s review process met the requirements that would ensure its compliance with Article 2 of the ECHR. The subsequent report of the HMIC was highly critical of the HET and in 2013 the PSNI announced that it would review all military cases relating to the period 1968 up until the Good Friday Agreement was signed, in order “to ensure the quality of the review reached the required standard”.

The Legacy Investigations Branch

As a result of budget cuts to the Police Service of Northern Ireland, the HET was disbanded in September 2014. In its place the PSNI stated that a much smaller Legacy Investigations Branch (LIB) would be formed.

The LIB continues to review all murder cases linked to the Troubles. That review does not examine cases chronologically but uses a case sequencing model, which looks at forensic opportunities, available witnesses and other investigative material when deciding which cases to tackle first. The PSNI has stated that it does not prioritise military cases, which account for approximately 30% of its workload.

Any decision by the LIB to prosecute is referred to the Director of Public Prosecutions for Northern Ireland. The MOD, and the British Government, is entirely independent of this process.

There has been significant criticism, on all sides, of the process by which legacy investigations have been, and continue to be, undertaken. Concerns have been expressed over the credibility and reliability of evidence and witness statements that may be over 40 years old and the re-opening of investigations that had already concluded. Most notable has been the widespread perception that investigations have disproportionately focused on the actions of the armed forces and former police officers, which account for 30% of the LIB’s workload but only form 10% of the overall deaths during the Troubles.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission

The big question for many people has been why a South African-style truth and reconciliation commission for Northern Ireland was not commissioned whereby witnesses would get immunity from prosecution in an attempt to deal with the legacy of the Troubles, including combatants from all sides.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was a court-like restorative justice body assembled in South Africa after the end of apartheid. Witnesses who were identified as victims of gross human rights violations were invited to give statements about their experiences, and some were selected for public hearings. Perpetrators of violence could also give testimony and request amnesty from both civil and criminal prosecution.

The TRC, the first of the 1003 held internationally to stage public hearings, was seen by many as a crucial component of the transition to full and free democracy in South Africa. Despite some flaws, it is generally (although not universally) thought to have been successful.

The Institute for Justice and Reconciliation was established in 2000 as the successor organisation of the TRC.

The giving of statements and amnesty from prosecution would have gone a long way to help bereaved families from all sides of the troubles.

Help Us Sustain Ad-Free Journalism

Sorry, I Need To Put Out the Begging Bowl

Independent Journalism Needs You

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands