There is an estimated 210,000 children in England that do not have a safe home, a report from Bleak houses suggested.

Growing up in a stable, healthy and secure home is so important for any child. Yet we know there are thousands of children in England who are living in homeless families, stuck in poor quality temporary accommodation, often with low prospects of finding something permanent. There are many others who are at risk of ending up homeless.

There are around 4 million children in the UK growing up in poverty. And those poverty rates have risen for every type of working family – lone-parent or couple families, families with full and part-time employment and families with different numbers of adults in work.

This is the first time in two decades this has happened, and incredibly it is happening at a time of rising employment.

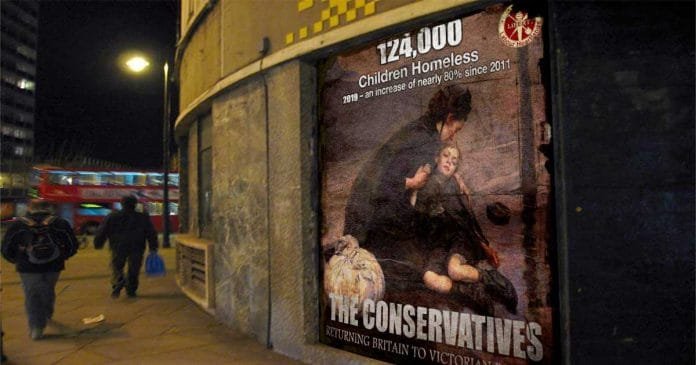

The government statistics show that there were 62,000 homeless families living in temporary accommodation in England at the end of 2018. Among these families were 124,000 children. This means that there are 80% more children living in temporary accommodation than in 2010.

This does not take in consideration the hidden homeless who are ‘sofa-surfing’, said Anne Longfield, Children’s Commissioner for England, who published the report.

Analysis for the commissioner estimates that in 2016/17 there were 92,000 children living in sofa-surfing families, taking the total of homeless children to an estimated 210,000.

The Housing Act 1996 requires that temporary accommodation be “suitable”, with the suitability depending on “the relevant needs, requirements and circumstances of the homeless person and their household”, according to local authority guidance.

Findings suggest that despite this guidance, many families are forced to stay in accommodation that is “wholly inappropriate to their needs”, the report explains.

“Due to the level of demand and shortage of permanent council accommodation, families frequently spend long stretches living in this ‘temporary’ housing, suffering desperately poor conditions for months if not years.”

Flats or houses with their own kitchen and bathroom are costly and in short supply, the commissioner said, and therefore families are placed in accommodation that is of poor quality and too small.

Longfield highlighted the types of accommodation that are of particular concern:

- Office block conversions and warehouses

This is a recent and “deeply worrying” development. The report cites the 2013 introduction of permitted development rights, which has seen office blocks and warehouses converted to residential as a reason why. It says that some areas are hotspots for permitted development, such as Harlow, where, according to Local Government Association (LGA) research, more than half of all new homes have been created through office conversions.

The commissioner says there is high demand for temporary accommodation in these blocks from central London councils seeking alternatives to higher cost rents within their own boroughs, leading to accusations that areas like Harlow are being used to “socially cleanse” the capital.

- Shipping containers

Several areas, including Brighton, Ealing and Bristol*, are using shipping containers as temporary accommodation. The land on which they are sited is usually earmarked for future development, but is not currently in use. The research found that shipping containers continue to be an attractive option to councils, as they don’t cost as much as B&Bs.

Antisocial behaviour is a problem with both office blocks and shipping containers.

- B&Bs

Other residents in B&Bs could be families, but they might also be vulnerable people with mental health issues or drug addictions, making the environment unsafe.

Some areas no longer use B&Bs, but it continues in others, despite the introduction of a legal limit in 2003 that means families can only be housed in a B&B in emergencies, when no other accommodation is available, and for no longer than six weeks. In December 2018 there were 2,420 households with children living in B&Bs, according to government statistics. Of these, a third had been there for more than six weeks. The National Audit Office (NAO) has heard of families being housed illegally in this way for as long as 30 months.

The commissioner warns that official figures don’t consider the small but vulnerable group of homeless children who have been placed in temporary accommodation by children’s services rather than by the council’s housing department, for which there isn’t publicly available data. This includes families who have been deemed to have made themselves “intentionally homeless”.

Risks associated with poor temporary accommodation leave children without anywhere to play safely, while parks and leisure centres might not be nearby or cost too much to use.

Longfield said: “Something has gone very wrong with our housing system when children are growing up in B&Bs, shipping containers and old office blocks. Children have told us of the disruptive and at times frightening impact this can have on their lives. It is a scandal that a country as prosperous as ours is leaving tens of thousands of families in temporary accommodation for long periods of time, or to sofa surf.

“It is essential that the government invests properly in a major house-building programme and that it sets itself a formal target to reduce the number of children in temporary accommodation.”

Simone Vibert, report author and senior policy analyst at the Children’s Commissioner’s office, added: “Frontline professionals working with children and families need greater training to spot the early signs of homelessness, and councils urgently need to know what money will be available for them when current funds run out next year.”

Reaction:

Polly Neate, chief executive of Shelter, said the report is a “damning indictment” of the government’s “catastrophic failure” to address the housing emergency.

“No child should be spending months if not years living in a converted shipping container, a dodgy old office block or an emergency B&B. But a cocktail of punitive welfare policies, a woeful lack of social homes and wildly expensive private rents means this is frighteningly commonplace. We constantly hear from struggling families forced to accept unsuitable and sometimes downright dangerous accommodation because they have nowhere else to go. The devastating impact this has on a child’s development and wellbeing cannot be overstated.

“The message to this government should be clear: to stop more children from suffering we must urgently increase housing benefit so families can at least afford the basic cost of rent, alongside a long-term commitment to build three million more social homes. This is the only way to guarantee the next generation can have the stability of a safe roof over their head.”

The LGA’s housing spokesman Martin Tett, said the “severe lack” of social rented homes available in which to house families means councils have no choice but to place households into temporary accommodation.

“With homelessness services facing a £159 million funding gap next year (2020/21), the government needs to use the upcoming Spending Round to ensure councils have long-term sustainable funding to prevent homelessness, and give councils the tools they need to resume their historic role of building homes with the right infrastructure that the country needs. This includes allowing councils to keep 100 per cent of receipts of council homes sold under Right to Buy, so that they can be reinvested in new replacement homes, and the ability to set Right to Buy discounts locally.”

He added that permitted development rights should be scrapped.

Bleak Houses: Tackling the crisis of family homelessness in England can be found on the Children’s Commissioner for England website (pdf).

* The report notes that Bristol City Council has clarified it does not direct families to shipping container sites but provides land for them, which are operated solely by a charity.

Related links.

Children in absolute poverty across UK hits 3.7 million after increases of 200,000 in a year

A rigged system, 26 individuals own the same as poorest 50% of humanity

Malnutrition cases treated by the NHS have almost trebled under Tory government

Government broken promises on rough sleeping cutting fund by up to £80m

Foodbanks are not just a photo opportunity for Tory MPs’ says Jeremy Corbyn

Help Us Sustain Ad-Free Journalism

Sorry, I Need To Put Out the Begging Bowl

Independent Journalism Needs You

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands