What is a Universal Basic Income (UBI)?

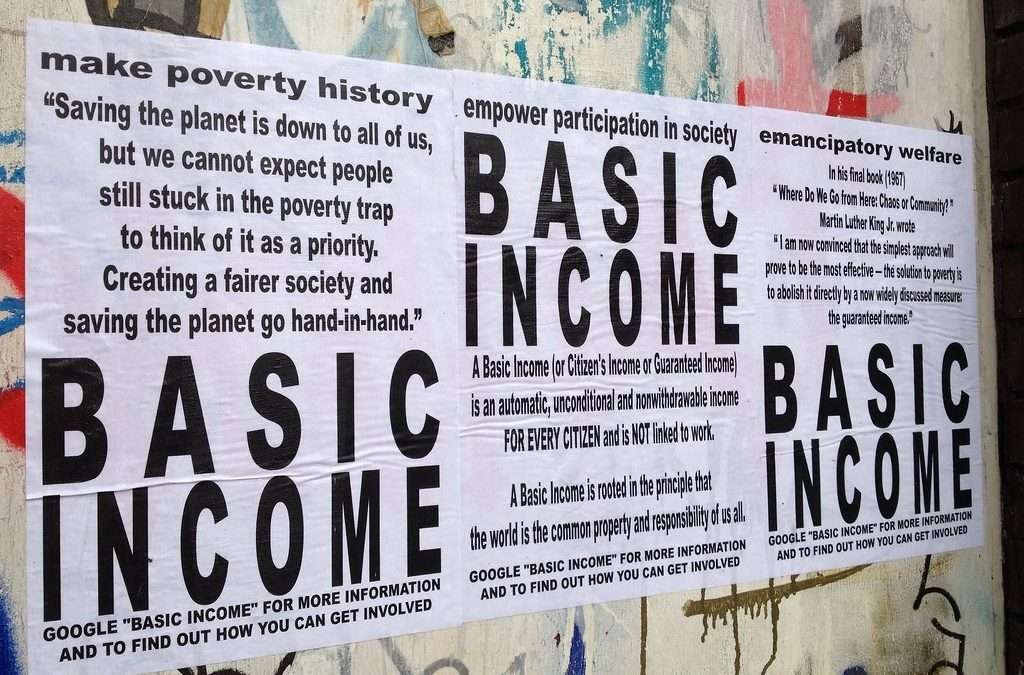

On its face, the definition of a truly universal basic income is pretty straightforward: It’s an amount of cash given to everyone within a geographic area that’s then distributed unconditionally, regularly, and on a long-term basis. (Although, the most recent UBI trials have focused on those with low incomes. There are varying opinions about whether the wealthy should also receive UBI payments, or whether they should be distributed on a sliding scale based on income.)

During the Great Depression, Milton Friedman, an economist with a reputation for being a radical libertarian, started thinking about how to implement what he was calling a guaranteed minimum income, which was primarily focused on providing enough money for nutritional needs. At the time, Friedman was not well-known, and the idea gained little traction.

He later proposed a negative income tax, a system in which individuals earning below a particular threshold receive funds from the government, rather than paying taxes. The concept of negative income tax helped lay some of the groundwork for conceptualising UBI.

While it does not yet exist as a practical reality in the UK, the concept of a universal basic income – or UBI – is similar to the concept of minimum wage. Each individual receives an agreed-upon minimum income (basic income) with the intent that the income allows a person to afford the basic cost of living while maintaining some semblance of financial security or independence.

Finland introduced a “Universal Basic Income” for a small number of its citizens as an experiment. The Finnish government’s idea was that it would study the possibility of using UBI as a way to offset the unemployment caused by automation.

According to the Guardian, the Finnish two-year pilot program was found to have “improved the wellbeing” of 2,000 randomly selected people across the country who were given €560 a month.

The recipients of the money were not required to give up their jobs or any governments benefits they might have been receiving.

No one knows for sure whether UBI would actually lead to economic recovery, or whether it would prove to be a slippery slope down to the kind of economic stagnation that the old “Eastern Bloc” countries, Russia included, suffered for decades.

Prof Helena Blomberg-Kroll, who led the Finnish study, suggested that the results were inconclusive, probably because the sample size was too small.

Blomberg-Kroll said: “Some said the basic income allowed them to go back to the life they had before they became unemployed, while others said it gave them the power to say no to low-paid insecure jobs, and thus increased their sense of autonomy.”

But she added that the idea should not be dismissed. “While basic income can’t solve all our health and societal problems, there is certainly a discussion to be had that it could be part of the solution in times of economic hardship.”

And that is the criticism many people have of the UBI – it’s a regular amount of money, perhaps monthly, paid to everyone, regardless of need, and probably would make people lazy.

The coronavirus pandemic has opened the door to radical economic reform, argues FT columnist Martin Sandbu. A no-strings regular cash transfer to everyone could shake up the welfare system, bring new economic security, and create more opportunities for all. Welcome to Free Lunch on Film where unorthodox economic ideas are put to the test.

Watch the video…

Coronavirus: Spain announces €3-billion universal basic income scheme

The idea is being supported by politicians, to the extent that Spain has announced a €3 billion UBI program, as reported by The Local.

Spain’s socialist Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez said the program would “help four out of five people in severe poverty and benefit close to 850,000 households, half of which include children”.

Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez said the government was committed to reducing poverty.

“It will cost around €3 billion per year, will help four out of five people in severe poverty and benefit close to 850,000 households, half of which include children,”

The reason for the renewed, or in most cases entirely new, interest in UBI is the economic devastation caused by the coronavirus pandemic, or more specifically, the resulting lockdowns and social distancing rules that most countries introduced, which put the brakes on virtually every sector of every country’s economy.

Now, as the world looks like it will live under constant restrictions and local lockdowns if required, UBI is looking like a good idea to stimulate economic activity at the same time as helping people at the lower end of the socio-economic ladder.

Meanwhile, an organisation called the Basic Income Earth Network – unsurprisingly – has been highlighting various countries’ and regions’ support for UBI.

In the US, where almost 27 million new people have signed up for benefits sinch mid-March 2020 amid the coronavirus chaos, the idea of UBI is less widely discussed, as can be expected in a free-market economy where self-reliance is paramount.

The government has introduced aid programs which it may limit itself to, but one group of academics is pointing to the state of Alaska’s practice of paying each resident almost $2,000 a year simply for living in the state, implying that UBI is not really an alien communist plot to take over the world.

In an article the academics had published in The Regulatory Review, they note: “Public support for a national universal basic income has grown significantly in the last decade, and recent studies indicate that Americans are now split with roughly equivalent support for and against UBI.

“Indeed, some scholars argue that the damage caused by Covid-19 has revealed a fragile and inequitable economy and that the recent one-time payment should become a regular feature to give everyone basic financial security going forward.”

A pivotal moment: radical goes mainstream

The coronavirus outbreak and its fallout, which experts agree will be long and painful, has shifted policy proposals that a short time ago were dismissed as radical and fringe, such as UBI and MMT now they are being intruduced into the mainstream.

“I believe the economic crisis that is going to come will cause more death and misery than the coronavirus outbreak itself,” says Standing, who co-founded Basic Income Earth Network in 1986. He predicts “widespread chaos” if prime minister Boris Johnson’s government “throws lots of money wildly into job-retention schemes”, mostly because the cash won’t reach “where it needs to get”.

Together with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) there is a new hope.

Quantitative Easing (or QE as it is more widely known) is a type of monetary policy, used by the Bank of England to purchase financial products, such as gilts and other bonds, on the open market in exchange for bank deposits. Since bank deposits generally pay less interest than gilts the economy receives less interest income overall.

The Bank of Englan is printing money from fresh air to stimulate the ecconomy, in much the same way MMT argues this can while under control continue and be used for the common good. Giving people money to spend is now viewed as a more effective method of simulation and kick starting a flatlined economy.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is an economic theory that suggests that the government could simply create more money without consequence as it’s the issuer of the currency.

It might be noted that a leading advocate of MMT, Professor Stephanie Kelton, is serving as an advisor to President Joe Biden.

The Green New Deal Plus Modern Monetary Theory = Socialism

Chris Williamson has also been discussing MMT again this breaks with traditional thinking and challenges the dogma that running the economy is like running a household budget.

Despite the myths that have been told time and time again, states are NOT households – they run armies and banks and schools and police forces and so on.

They allocate expenditure in expectation of getting an equivalent amount of money back through taxation. There is no direct connection between public expenditure and public income. There is no state piggy bank or housekeeping allowance.

Despite the claim that states ‘printing’ money is automatically inflationary, this is not the case. What matters is the relationship between state income and expenditure and the condition of the wider economy.

The skill is to balance the money created with the money recovered via taxation. In any case, public deficits can be a good thing. They put fresh money into the economy that is then free to circulate.

MMT asks serious questions about austerity and gives real-life answers to public spending.

This again is very dangerous thinking it liberates the confines of capital enslavement for a socialist agenda more so it exposes the reality of the magic money tree.

Prof Andrew Baker of Sheffield University and “anti-poverty campaigner and tax expert” Prof Richard Murphy were awarded the Cambridge University Press Award for Excellence in Social Policy Scholarship for their article “Modern Monetary Theory and the Changing Role of Tax in Society” in the academic Social Policy Association’s 2021 Awards round.

This important paper uses insights from Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) to show that rather than taxing first and then spending the resulting revenues, governments first spend, bringing money into existence in the process, and then effectively recover some of that outlay through taxation. This is a spend and tax cycle, rather than the tax and spend cycle that most people, politicians included assume exists. Narratives of public spending as taxpayers’ money don’t make much sense in this context: all money is actually created by the government when understood in this way.

The article shows how thinking about tax in this way brings its role as an instrument of social policy more sharply into focus. It also highlights its capacity to incentivise some economic activities and disincentivise others. In that way we suggest that tax can itself be used as a tool to shape society, or to achieve objectives governments and electorates agree to prioritize by shaping incentives, prices and redistributive patterns.

In layman’s terms we can achieve the unachievable, if money is no object.

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands