The number of legal cases against members of the Catholic Church is on the rise, as the German government takes a harder stance against asylum seekers taking refuge in churches.

Juliana Seelmann, a nun from the Franciscan nunnery at the Oberzell monastery in southern Germany, was found guilty this week of aiding the unauthorized residence in Germany of two Nigerian women. She was fined several hundred euros.

She had aided two women from Nigeria who said they were trying to escape forced prostitution in Italy, where they had first fled to. After German officials sent them back to Italy, where forced prostitution again awaited them, they were able to find their way into the church’s protection, under a practice often referred to in Germany as “church asylum.”

Juliana Seelmann was found guilty of aiding the unauthorized residence in Germany of Nigerian refugees

Church asylum means the temporary admission of refugees by a parish in order to avert deportation. The aim is the resumption or reexamination of the asylum or immigration procedure for the individual refugee. The practice has a long history in Germany.

After the influx of refugees to Germany in 2015 and 2016, several asylum-seekers saw their applications rejected.

Churches prevented 498 deportations in the first quarter of 2018, but in 2019 authorities rejected almost all church asylum cases. The nuns and priests point to article 4 of the German constitution, which guarantees the freedom of faith and conscience.

That is also what nun Seelmann cited in her defence. “People in such a terrible situation need help,” she told DW news.

Thürmer argues that in the end, no German court would find someone guilty for trying to help — it is a Christian’s “highest duty.” A guilty verdict would be simply “inhumane,” she said.

“Every person’s dignity is equal,” she added, paraphrasing the German constitution. “It says, ‘every person.’ Not ‘every German.'”

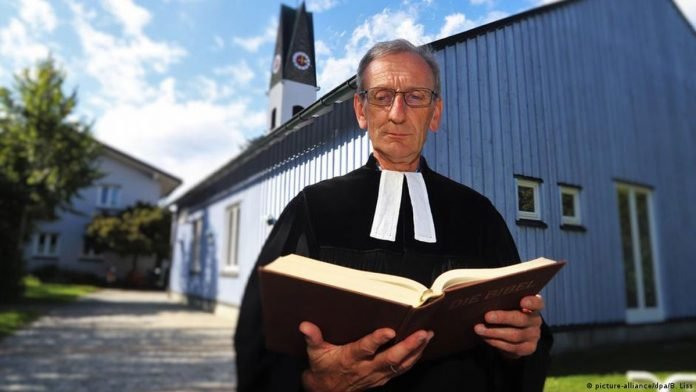

In 2019, Protestant pastor Ulrich Gampert was sentenced by a court in southern Germany to pay a fine of €3,000 for taking in an Afghan refugee who had been scheduled for deportation.

Making church asylum ‘more difficult’

The latest round of cases does not come as a surprise to Dieter Müller, a Jesuit and deputy chairman of the nonprofit Asylum in the Church. Müller told DW that there has been a “steep rise” in investigations into church asylum in Bavaria since 2017. The southern state’s public prosecutor confirmed this. Many of the hundreds of cases against church officials and other members have been dismissed.

“I’ve had four cases against me, all dismissed,” Müller said, though criminal charges are now afoot.

“We’re witnessing an escalation,” he said. “The case won’t be dismissed. Instead, it’ll be fully prosecuted in court because three people have so far refused to pay fines.”

The state’s legal action is an “effort to make church asylum more difficult,” Müller said.

Protestant Pastor Ulrich Gampert was sentenced to a fine of €3,000 for taking in an Afghan refugee

Germany introduced a hardship commission in 2005, which re-examines individual cases of rejected asylum seekers. This offers an alternative to church asylum and offers individuals a legal possibility for having their cases revisited.

German politicians rarely comment on the issue of church asylum. But in what is termed a “major election year,” activists took the opportunity of an Ecumenical Church Congress in Frankfurt in May to write to the three leading politicians who were present.

Recently, a group of church officials and laypeople put the question of church asylum to top politicians in a letter-writing campaign. Armin Laschet of the Christian Democrats, Olaf Scholz of the Social Democrats, and Annalena Baerbock of the Green party are running to replace Angela Merkel as chancellor in September’s general election.

All three were asked whether church asylum can be legally justified. So far only Baerbock replied, writing: “It must not be that this act of Christian charity is made impossible by the threat of punishment from the state.”

The Green party politician, who has been riding high in the polls, went on to say that church asylum is often the last “lifeline” for those affected. A constitutional state that wants to prevent this “shows weakness, not strength,” she said.

This text has been translated from German.

Help Us Sustain Ad-Free Journalism

Sorry, I Need To Put Out the Begging Bowl

Independent Journalism Needs You

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands