The unprecedented swiftness with which medical science is developing a vaccine for COVID-19 is one of the most inspiring stories in this historic chapter.

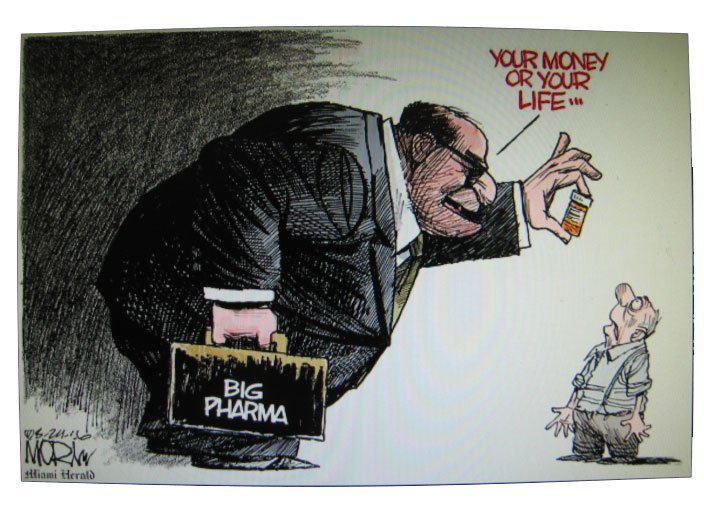

Vaccine candidates emerged only weeks after scientists identified SARS-CoV-2 and sequenced its genetic code. Universities and Big Pharma formed teams to develop a vaccine in short order. And while the chances of an effective vaccine are rising so is concern about who is behind the vaccine.

The more we know about the big pharma in the race for a vaccine the more the public distrust.

That ends up being an untenable situation, the medical and scientific task of developing a COVID-19 vaccine is not the only critical ingredient to a successful vaccination campaign public buy-in is essential, a vaccine is only effective when people agree to be inoculated and when the front runner turns out to be Pfizer questions need to be asked.

First, it should be stated I am not an anti-vaxxer, I am also very aware that vaccines save life’s and that a vaccine is necessary, however in the race to find a vaccine we should not accept just any vaccine, especially one coming from Pfizer. In this race to bring a Covid 19 vaccine to market, it has had many of the checks and balances related to bringing new Medicines to the market removed.

Personally I’ve probably had more vaccines than most being ex-forces, I really don’t fear a vaccine and understand its necessity, however, I have witnessed firsthand the results of ill-prepared bad vaccines and what they can do to fit young men who took them and that outcome was Gulf War syndrome.

The illness known as Gulf war syndrome looks likely to have been caused by an illegal vaccine “booster” given by the Ministry of Defence to protect soldiers against biological weapons, according to the results of a new series of tests.

Scientists in the United States found that symptoms of the illness were the same for service personnel who received the injections whether or not they served in the Gulf.

The common factor for the 275,000 British and US veterans who are ill appears to be a substance called squalene, allegedly used in injections to add to their potency.

Soldiers who were given vaccinations in the US and the UK were given something they should not have been, probably in the anthrax vaccine. [The results] need a thorough examination by the US and UK governments.”

Squalene is classed as an ad juvant – a chemical which is added to a vaccine to make it more combative. It is a naturally occurring substance in the human body but injecting it is illegal, and past scientific research in rats and mice has found that it causes auto-immune disease. Consequently, squalene in the form of a vaccine is unlicensed for human or veterinary use. Read more

If the Government at the time could be so carefree with what they injected into our armed forces, it is incumbent on us the public to make sure they are more vigilant going forward, especially when this is a Tory government and the entire nation are about to be inoculated.

If the government are to trust Pfizer to vaccinate the nation, it’s only fair we inquire into its history of safety and ethics.

Pfizer is a New-York based Big Pharma company. It’s known for its products like Advil, Viagra, Xanax and Zoloft. It was the second-largest pharmaceutical company in revenue in 2020. But the medical industry giant has had its share of legal troubles and scandal. This includes marketing fraud allegations and unapproved clinical trials.

Pfizer made itself one of the largest pharmaceutical company in the world in part by purchasing its competitors. In the last dozen years, it has carried out three mega-acquisitions: Warner-Lambert in 2000, Pharmacia in 2003, and Wyeth in 2009. Then, in 2015, Pfizer announced a $160 billion deal to merge with Allergan and move its headquarters to Ireland to avoid U.S. taxes but subsequently had to abandon the plan.

The acquisition, which would have created the world’s largest ‘drugmaker’ shifting Pfizer’s headquarters to Ireland, would also have been the biggest-ever instance of a U.S. company re-incorporating overseas to lower its taxes. This created a political backlash from all parties united in their condemnation. The U.S. President at the time Barack Obama called such inversion deal unpatriotic.

The Democratic presidential front-runner Hillary Clinton pledged to propose measures to prevent such deals. The merger was also slammed by her rival Senator Bernie Sanders as well as by Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump.

“The fact that Pfizer is leaving our country with a tremendous loss of jobs is disgusting,” Trump said in a statement.

It was not immediately known how many jobs would be lost as a result of the merger.

What this did show was the fact ‘Pfizer’ has no loyalty but to itself.

Many people would reflect in a capitalist world of ‘dog eat dog’ Pfizer is just doing what big pharma does, buying out the competition while looking to maximise their profits. If only that was the case, we could all swallow the bitter pill understanding that big dogs win races and we must take our medicine like good little plebs, however, there is much more to Pfizer’s story and that’s where our trust begins to wane.

Pfizer: Corporate Rap Sheet.

Pfizer Admits Bribery in Eight Countries

Pfizer has also grown through aggressive marketing—a practice it pioneered back in the 1950s by purchasing unprecedented advertising spreads in medical journals. In 2009 the company had to pay a record $2.3 billion to settle federal charges that one of its subsidiaries had illegally marketed a painkiller called Bextra. Along with the questionable marketing, Pfizer has for decades been at the centre of controversies over its pricing, including a price-fixing case that began in 1958.

In the area of product safety, Pfizer’s biggest scandal involved defective heart valves sold by its Shiley subsidiary that led to the deaths of more than 100 people. During the investigation of the matter, information came to light suggesting that the company had deliberately misled regulators about the hazards. Pfizer also inherited safety and other legal controversies through its big acquisitions, including a class action suit over Warner-Lambert’s Rezulin diabetes medication, a big settlement over PCB dumping by Pharmacia, and thousands of lawsuits brought by users of Wyeth’s diet drugs.

Also on Pfizer’s list of scandals are a 2012 bribery settlement; massive tax avoidance; and lawsuits alleging that during a meningitis epidemic in Nigeria in the 1990s the company tested a risky new drug on children without consent from their parents.

For three years, Pfizer Italy employees provided free cell phones, photocopiers, printers and televisions to doctors, arranged for vacations (such as “weekend in Gallipoli,” “weekend with companion” and “weekend in Rome”) and even made direct cash payments (under the guise of lecture fees and honoraria) in return for promises by doctors to recommend or prescribe Pfizer’s products.

Today, the New York headquarters of the pharmaceutical giant has agreed to pay a total of $60.2 million in penalties to settle the documented charges of bribery. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) says that Pfizer Italy employees went out of their way to “falsely” book the expenses under “misleading” labels like “Professional Training,” and “Advertising in Scientific Journals.”

The penalty is roughly half a percent of the company annual profits that exceed $10 billion a year on global sales of $67.4 billion in 2011.

Italy was not the only country where Pfizer has been accused of bribing doctors and local officials. “Pfizer took short cuts to boost its business in several Eurasian countries, bribing government officials in Bulgaria, Croatia, Kazakhstan and Russia to the tune of millions of dollars,” says Mythili Raman, the principal deputy assistant attorney general of the U.S. Department of Justice’s (DoJ) criminal division.

“Pfizer H.C.P. admitted that between 1997 and 2006, it paid more than $2 million of bribes to government officials in Bulgaria, Croatia, Kazakhstan and Russia,” notes a press release issued by the DoJ. “Pfizer H.C.P. also admitted that it made more than $7 million in profits as a result of the bribes.”

Amy Schulman, executive vice-president and general counsel for Pfizer, said: “The actions which led to this resolution were disappointing, but the openness and speed with which Pfizer voluntarily disclosed and addressed them reflects our true culture and the real value we place on integrity and meeting commitments.”

In a criminal complaint issued by the SEC, investigators laid out detailed charges for a total of eight countries: Bulgaria, China, Croatia, Czech Republic, Italy, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Serbia.

For example, for almost six years, Pharmacia Croatia made monthly payments of approximately $1,200 per month into the Austrian personal bank account of a Croatian doctor. In 2003, Pfizer bought Pharmacia Croatia but allowed the payments to continue for three months.

A memo from a senior manager noted that the doctor was “a member of the Registration Committee regarding pharmaceuticals, I do expect that all products which are to be registered, will pass the regular procedure by his assistance. . . . He is a person of great influence in Croatia in the area of pharmaceuticals, and his opinion is respected very much; that’s the reason he is so important to us.”

In Russia, from the mid-1990s through 2005, Pfizer Russia had a special sales initiative called the “Hospital Program” under which employees were allowed to pay hospitals five percent of the value of certain Pfizer products. Some of this money was paid out in cash to individual Russian doctors “to reward past purchases and prescriptions and induce future purchases and prescriptions of Pfizer products.”

Government officials were also cultivated. On November 19, 2003, a Pfizer Russia employee sent in an invoice requesting “payment for the (motivational) trip of [the First Deputy Minister of Health] for the inclusion of [a Pfizer product] into the list . . . of medications refundable by the state.”

In another email June 27, 2005, a Pfizer Russia employee noted that a government doctor “should be assigned the task of stretching the amount of the purchases . . . to US $100 thousand” as an “obligation” in exchange for a trip to a conference in the Netherlands or Germany.

Federal officials have forced Pfizer to pay much higher fines in the past, based on the damage assessed in each case (typically a multiple of the damages). For example in 2009, Pfizer paid out $2.3 billion to settle allegations of criminal and civil liability arising from the illegal promotion of Bextra, an anti-inflammatory drug.

The UK’s competition regulator is pushing to reinstate a £90m fine for Pfizer and Flynn Pharma – quashed last year – over price hikes for an epilepsy drug.

The case dates back to 2015, when the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) accused the two companies of dramatically raising the price of phenytoin sodium, a drug that has been used to treat epilepsy for decades, which at the time was manufactured by Pfizer and sold in the UK by Flynn.

A report in the Financial Times says the CMA is arguing that an appeals tribunal erred in law when it backed the companies’ appeal against the fine, which was levied in 2016 and set damages of £84.2m for Pfizer and £5.2m for Flynn.

Pfizer originally sold the drug as Epanutin and – according to the CMA – the NHS spent around £2.3m a year on the drug before it sold the UK distribution rights to Flynn in 2012. It is estimated that around 50,000 people in the UK rely on phenytoin to control seizures.

Flynn de-branded the product and hiked the price by up to 2,600%, says the CMA, and as a result the amount the NHS was charged for 100mg packs of the drug rocketed from £2.83 to £67.50, before reducing to £54.00 from May 2014.

In 2013, the cost of the drug to the NHS rocketed up to £50m, according to the authority, which maintains that the increases resulted from a monopolistic position that had been abused.

At the time the complaint was first raised, Pfizer argued that the price of the drug had been set at a level that was profitable in order to ensure a stable supply, while Flynn indicated the price it charged was in line with rival drugs.

“When Flynn launched its product, the company set a price that was between 25 and 40% less than the price of the equivalent medicine from another supplier to the NHS which had long been regulated, and appeared to be acceptable to, the Department of Health,” it said.

The FT notes that when the £90m judgment was struck down last year, the tribunal concluded that in general “price control is better left to sectoral regulators, where they exist, and operated prospectively; ex post price regulation through the medium of competition law presents many problems”.

According to court filings, the CMA is arguing that “if pharmaceutical companies are entitled to charge unfairly high prices in circumstances such as those in this case, this has a serious knock-on effect on the resources of clinical commissioning groups and patient care”.

U.S. government regulators hand out billions in fines to multinational corporations, estimates the New York Times. “Critics remain, however, arguing that the practice of settling fraud cases with companies while not charging any employees might be giving executives an incentive to push the limits of the law,” notes the newspaper.

“If you are an executive, you know that the chances of getting caught are infinitely small, and the chances of getting caught and prosecuted are even smaller,” Dennis M. Kelleher, president of Better Markets, told the New York Times.

Words come easy, actions speak for themselves

Drug company executives, including Pfizer, have previously insisted they aren’t cutting corners in fast-tracking development of potential vaccines. They have said the Food and Drug Administration hasn’t eased its requirements for proving their vaccines are safe and effective.

Excuse the interruption!

While you are here please consider giving a small donation.

We would really appreciate your support for Labour Heartlands by making a small donation to keep us running Ad-Free

We really do appreciate any donation, large or small.

CLICK THE IMAGE TO DONATE

While the vaccine may be safe, the executives have said it is “understandable” the public would be concerned, adding they will need to work to gain that trust.

Albert Bourla is the chairman and chief executive officer of Pfizer said that the company “would never” submit any vaccine for authorization before “we feel it is safe and effective.”

“We will not cut corners,” he said. “Our phase three study will be the only one that will allow us to say if we have a safe and effective vaccine. If we don’t have results from a phase three study, we would not submit.”

Pfizer’s long history not baking up their words with actions.

Product Safety

Philip Mattera from Corporate Research gives an extensive rap sheet of Pfizer’s history starting in the mid-1980s, watchdog organisations such as the Public Citizen Health Research Group charged that Pfizer’s widely prescribed arthritis drug Feldene created a high risk of gastrointestinal bleeding among the elderly, but the federal government, despite reports of scores of fatalities, declined to put restrictions on the medication. A June 1986 article in The Progressive about Feldene was headlined DEATH BY PRESCRIPTION.

The Food and Drug Administration expressed greater concern about reports of dozens of fatalities linked to heart valves made by Pfizer’s Shiley division. In 1986, as the death toll reached 125, Pfizer ended production of all models of the valves. Yet by that point, they were implanted in tens of thousands of people, who worried that the devices could fracture and fail at any moment.

In 1991 an FDA task force charged that Shiley had withheld information about safety problems from regulators in order to get initial approval for its valves and that the company continued to keep the FDA in the dark. A November 7, 1991 investigation in the Wall Street Journal asserted that Shiley had been deliberately falsifying manufacturing records relating to valve fractures.

Faced with this growing scandal, Pfizer announced that it would spend up to $205 million to settle the tens of thousands of valve lawsuits that had been filed against it. Even so, Pfizer resisted complying with an FDA order that it notifies patients of new findings that there was a greater risk of fatal fractures in those who had the valve installed before the age of 50. In 1994 the company agreed to pay $10.75 million to settle Justice Department charges that it lied to regulators in seeking approval for the valves; it also agreed to pay $9 million to monitor valve patients at Veterans Administration hospitals or pay for removal of the device.

In 2004 Pfizer announced that it had reached a $60 million settlement of a class-action suit brought by users of Rezulin, a diabetes medication developed by Warner-Lambert, which had withdrawn it from the market shortly before the company was acquired by Pfizer in 2000. The withdrawal came after scores of patients died from acute liver failure said to be caused by the drug.

In 2004, in the wake of revelations about dangerous side effects of Merck’s painkiller Vioxx, Pfizer agreed to suspend television advertising for a related medication called Celebrex. The following year, Pfizer admitted that a 1999 clinical trial found that elderly patients taking Celebrex had a greatly elevated risk of heart problems.

In 2005 Pfizer withdrew another painkiller, Bextra, from the market after the FDA mandated a “black box” warning about the cardiovascular and gastrointestinal risks of the medication. In 2008 Pfizer announced that it was setting aside $894 million to settle the lawsuits that had been filed in connection with Bextra and Celebrex.

With the acquisition of Wyeth (formerly American Home Products) in October 2009, Pfizer took on a new set of legal problems. The summary of legal proceedings in Wyeth’s last annual financial report before the deal was announced went on for 14 pages. Most of the lawsuits discussed were product liability cases involving hormone therapy, childhood vaccines, the anti-depressant Effexor, the contraceptive Norplant and, most importantly, the combination diet drug known as fen-phen, which had been withdrawn from the market after reports that its use was linked to possibly fatal heart valve damage. Those findings unleashed a wave of tens of thousands of lawsuits against the company.

Pricing

Pfizer has been at the centre of controversies over its pricing for more than 50 years. In 1958 it was one of six drug companies accused by the Federal Trade Commission of fixing prices on antibiotics. The company was also charged with making false statements to the U.S. Patent Office to obtain a patent on tetracycline.

In 1961 the Justice Department filed criminal antitrust charges against Pfizer, American Cyanamid, Bristol-Myers and top executives of the three companies. Two years later, the FTC ruled that the six companies named in its 1958 complaint had indeed conspired to fix prices on tetracycline. The commission also found that “unclean hands and bad faith played a major role” in the issuance of the tetracycline patent to Pfizer.

In 1964 the FTC ordered the six companies to reset their prices and told Pfizer to grant a production license for tetracycline to any company that applied for it. In 1967 a federal jury found Pfizer, American Cyanamid and Bristol-Myers guilty of conspiring to control the production and distribution of restraint of trade, conspiracy to monopolize and actual monopoly. The companies were each fined the maximum of $150,000, but payment was delayed while they pursued an appeal.

That effort was fruitful for the companies. In 1970 a federal appeals court ordered the case sent back to the district court for what it said were errors in the jury instructions by the judge. Three years later, another federal judge, sitting without a jury, dismissed the charges. In the interim, Pfizer and other companies had agreed to pay some $136 million to settle a class-action case and other civil suits that had been brought on behalf of consumers and state and local governments. Later settlements brought the amount to more than $150 million.

Pfizer, along with the other large pharmaceutical companies, were later targeted in a series of lawsuits brought by state attorneys general and other parties challenging the industry’s pricing practices. In 1996 Pfizer was one of 15 large drug companies that agreed to pay more than $408 million to settle a class action lawsuit charging that they conspired to fix prices charged to independent pharmacies.

In 1999 Pfizer pleaded guilty to criminal antitrust charges that its former Food Science Group unit took part in two international price-fixing conspiracies—one involving the food preservative sodium erythorbate and the other the flavour enhancer maltol. Pfizer agreed to pay fines totalling $20 million.

In 2000, amid widespread criticism of the high price of AIDS medications, Pfizer offered to donate a two-year supply of its drug Diflucan worth $50 million to the South African government. Yet in 2003, after acquiring Pharmacia Corp., Pfizer backed away from the company’s plan to license its AIDS drug Rescriptor for low-cost distribution in poor countries.

In 2002 Pfizer resisted cooperating with a General Accounting Office investigation of industry pricing practices but relented after chairman and CEO Henry McKinnell was served with a subpoena. Later that year, Pfizer agreed to pay $49 million to settle charges that one of its subsidiaries defrauded the federal Medicaid program by overcharging for its cholesterol-lowering drug Lipitor.

In 2003, as Congress was discussing legislation to legalize the importation of cheap prescription drugs from Canada, Pfizer sought to undermine the practice by telling major Canadian pharmacies that they would have to begin ordering directly from Pfizer rather than going through wholesalers. This put Pfizer in the position of cutting off supply if it suspected the pharmacies were selling to the U.S. market. The following year, Pfizer announced that it would begin requiring wholesalers to report on orders from individual drugstores.

In 2016 the Justice Department announced that Pfizer would pay $784 million to settle allegations that Wyeth underpaid rebates to Medicaid on two of its drugs.

Later in 2016 the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority fined Pfizer the equivalent of $107 million for charging excessive and unfair prices for an epilepsy drug.

Advertising and Marketing Controversies

After the Second World War, Pfizer caused a scandal when it circumvented the traditional drug distribution networks and began marketing its products (especially the antibiotic Terramycin) directly to hospitals and physicians, making unprecedented use of splashy advertisements in the Journal of the American Medical Association. A prominent article in the Saturday Review in 1957 denounced the company for tactics such as running ads for its antibiotics that displayed the names of doctors who were supposedly endorsing the product but who turned out to be fictitious.

In 1991 Pfizer paid a total of $70,000 to 10 states to settle charges relating to misleading advertising for its Plax mouth rinse.

1996 the Food and Drug Administration ordered Pfizer to stop making unauthorized and misleading medical claims for its antidepressant Zoloft.

In 2000 the FDA warned Pfizer and Pharmacia, co-marketers of the arthritis drug Celebrex, that the consumer ads they were running for the medication were false and misleading. Two years later, the FDA ordered Pfizer to stop running a series of magazine ads that the agency said misleadingly suggested that its cholesterol-lowering drug Lipitor was safer than competing products.

In 2003 Pfizer paid $6 million to settle with 19 states that had accused the company of using misleading ads to promote its Zithromax medication for children’s ear infections.

In 2004 Pfizer’s Warner-Lambert subsidiary agreed to pay $430 million to resolve criminal and civil charges that it paid physicians to prescribe its epilepsy drug Neurontin to patients with ailments for which the medication was not approved. Documents later came to light suggesting that Pfizer arranged for delays in the publication of scientific studies that undermined its claim for the other uses of Neurontin. In 2010 a federal jury found that Pfizer committed racketeering fraud in its marketing of Neurontin; the judge in the case subsequently ordered the company to pay $142 million in damages.

In 2007 Pfizer subsidy Pharmacia & Upjohn agreed to pay $34.7 million to settle federal charges relating to the illegal marketing of its Genotropin human growth hormone.

In 2009 Pfizer agreed to pay $2.3 billion to resolve criminal and civil charges relating to the improper marketing of Bextra and three other medications. The amount was a record for a healthcare fraud settlement. John Kopchinski, a former Pfizer sales representative whose complaint helped bring about the federal investigation, told the New York Times: “The whole culture of Pfizer is driven by sales, and if you didn’t sell drugs illegally, you were not seen as a team player.” As part of the settlement, Pfizer had to enter into a Corporate Integrity Agreement with the Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services.

In 2010 Pfizer disclosed that during a six-month period the previous year it had paid $20 million to some 4,500 doctors and other medical professionals for consulting and speaking on the company’s behalf. This was the first time the company had made public its spending of this kind.

In 2011 Pfizer agreed to pay $14.5 million to resolve federal charges that it illegally marketed its bladder drug Detrol.

In 2011 the FDA told Pfizer that its “Online Resources” webpage on Lipitor contained misleading statements.

In July 2012 Pfizer agreed to remove claims related to breast and colon health from its advertising for Centrum multivitamins as part of an agreement to settle a lawsuit brought by the Center for Science in the Public Interest charging that the claims were unsubstantiated.

In November 2012 Pfizer disclosed that it had taken a charge against earnings of $491 million in connection with an “agreement in principle” with the U.S. Department of Justice to settle charges relating to the improper marketing of the kidney transplant drug Rapamune by Wyeth. That agreement was finalized in July 2013. Pfizer later reached a $35 million settlement of Rapamune charges brought by more than 40 state attorneys general.

Bribery and Improper Payments

In 1976 Pfizer was one of the many companies that disclosed that it had made questionable payments to foreign government officials. The company said that about $265,000 had been paid to officials in three countries but did not identify them.

In August 2012 the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission announced that it had reached a $45 million settlement with Pfizer to resolve charges that its subsidiaries, especially Wyeth, had bribed overseas doctors and other healthcare professionals to increase foreign sales.

Environment

In 1971 the Environmental Protection Agency asked Pfizer to end its long-time practice of dumping industrial wastes from its plant in Groton, Connecticut in the Long Island Sound. The company was reported to be disposing of about 1 million gallons of waste each year by that method.

In 1991 Pfizer agreed to pay $3.1 million to settle EPA charges that the company seriously damaged the Delaware River by failing to install pollution-control equipment at one of its plants in Pennsylvania.

In 1994 Pfizer agreed to pay $1.5 million as part of a consent decree with the EPA in connection with its dumping at a toxic waste site in Rhode Island.

In 1998 Pfizer agreed to pay a civil penalty of $625,000 for environmental violations discovered at its research facilities in Groton, Connecticut.

In 2002 New Jersey fined Pfizer fined $538,000 for failing to properly monitor wastewater discharged from its plant in Parsippany.

In 2003, shortly after Pfizer acquired Pharmacia, the company (along with Solutia and Monsanto) agreed to pay some $700 million to settle a lawsuit over the dumping of PCBs in Anniston, Alabama.

In 2005 Pfizer agreed to pay $22,500 to settle EPA claims that the company failed to properly notify state and federal officials of a 2002 chemical release from its plant in Groton that seriously injured several employees and necessitated a major emergency response.

Also in 2005, Pfizer agreed to pay $46,250 to settle charges that its Pharmacia & Upjohn operation had violated federal air pollution rules at its plant in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

In 2008 Pfizer agreed to pay a $975,000 civil penalty to resolve federal charges that it violated the Clean Air Act at its former manufacturing plant in Groton, Connecticut in the period from 2002 to 2005.

Environmental groups in New Jersey have criticized as inadequate a clean-up plan devised by Pfizer and the EPA for the American Cyanamid Superfund site in Bridgewater, which is considered one of the worst toxic waste sites in the country. Pfizer inherited responsibility for the clean-up through its 2009 purchase of Wyeth.

Human Rights

Pfizer apparently engaged in questionable practices abroad as well. In 2000 the Washington Post published a major exposé accusing Pfizer of testing a dangerous new antibiotic called Trovan on children in Nigeria without receiving proper consent from their parents. The experiment occurred during a 1996 meningitis epidemic in the country. In 2001 Pfizer was sued in U.S. federal court by thirty Nigerian families, who accused the company of using their children as human guinea pigs.

In 2006 a panel of Nigerian medical experts concluded that Pfizer had violated international law. In 2009 the company agreed to pay $75 million to settle some of the lawsuits that had been brought in Nigerian courts. The U.S. case was settled in 2011 for an undisclosed amount.

Classified U.S. State Department cables made public in 2010 by Wikileaks indicated that Pfizer had hired investigators to dig up dirt on Nigeria’s former attorney general as a way to get leverage in one of the remaining cases. Pfizer had to apologize over the revelation in the cables that it had falsely claimed that the group Doctors Without Borders was also dispensing Trovan during the Nigerian meningitis epidemic.

Labor

In January 2012 a group of Pfizer employees in Puerto Rico filed suit against the company in federal court, charging that it failed to properly manage their pension plan and caused losses totaling hundreds of millions of dollars over the past decade.

Worker Safety

In 2010 a federal jury awarded $1.37 million to a former Pfizer scientist who claimed she was sickened by a genetically engineered virus at a company lab and was then fired for raising safety concerns.

Taxes and Subsidies

Pfizer is one of the numerous pharmaceutical companies that for many years took advantage of a provision in the Internal Revenue Code (Section 936) that gave special tax credits for their operations in Puerto Rico and was widely criticized as a form of corporate welfare. A 1992 report by the U.S. General Accounting Office found that Pfizer was enjoying $156,400 in tax savings for each of its 500 employees on the island. The amount was said to be 636 percent of the company’s compensation costs.

During the Clinton Administration, there was a move to eliminate Section 936, but Pfizer and other drug companies managed to get the termination phased out over a decade. During that period, drug companies began registering their Puerto Rican operations as foreign entities, which allowed them to escape taxes entirely as long as they did not send the profits back to the mainland United States.

Then the companies pressed Congress to enact a repatriation tax holiday that would allow them to bring all their foreign profits back home and pay an artificially low tax rate on them, supposedly to spur domestic job creation. When such a holiday was put into effect for 2005, Pfizer repatriated more foreign profits than any other company—$37 billion—and enjoyed an $11 billion tax break while cutting rather than increasing its U.S. workforce.

In 2014 Pfizer launched an effort to take over AstraZeneca that was designed not only to swallow a competitor but also to cut its tax bill by locating the headquarters of the combined operation in Britain. When AstraZeneca resisted the controversial move, Pfizer abandoned the bid. Then in November 2015 Pfizer announced a similar deal, worth $160 billion, to merge with Allergan and move the headquarters of the combined company to Ireland. The plan was dropped when the Obama Administration introduced new tax rules.

State and Local Subsidies

Connecticut. In 2001 Pfizer opened a new $270 million research facility in New London with the help of a $60 million subsidy package from state and local officials. The city also used its power of eminent domain to assemble the site used by the company, angering local residents and leading to a court challenge that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In that case, Kelo v. New London, the Justices upheld the city’s right to take private property for economic development projects. In 2009, however, Pfizer announced that it would close its New London operation and relocate 1,400 jobs to its campus in nearby Groton, Connecticut.

Michigan. In 2001, the company committed to an $800-million expansion of its Ann Arbor research laboratories after receiving a state and local tax subsidy package worth more than $70 million. Five years later, however, the company announced that it was abandoning the facility and eliminating more than 2,000 jobs. The company also said it would eliminate 250 jobs in Kalamazoo, where in 2003 it received a 20-year subsidy package worth up to $635 million.

New York. In 2003 New York City and State officials offered Pfizer up to $47 million in the hope that the company would create 2,000 new jobs at its Manhattan headquarters and other New York City locations while retaining more than 5,000 positions. By 2010 Pfizer had, instead, eliminated large numbers of jobs in the city, in part from the closing of its longtime manufacturing plant in Brooklyn. In December of that year, Pfizer agreed to pay the city a penalty of $24.7 million—twice the tax subsidies it had received.

Coronavirus: First ‘milestone’ vaccine offers 90% protection

The drugmaker Pfizer announced on Monday that an early analysis of its coronavirus vaccine trial suggested the vaccine was robustly effective in preventing Covid-19, a promising development as the world has waited anxiously for any positive news about a pandemic that has killed more than 1.2 million people.

Pfizer, which developed the vaccine with the German drugmaker BioNTech, released only sparse details from its clinical trial, based on the first formal review of the data by an outside panel of experts.

The company said that the analysis found that the vaccine was more than 90 percent effective in preventing the disease among trial volunteers who had no evidence of prior coronavirus infection. If the results hold up, that level of protection would put it on par with highly effective childhood vaccines for diseases such as measles. No serious safety concerns have been observed, the company said.

A vaccine – alongside better treatments – is seen as the best way of getting out of the restrictions that have been imposed on all our lives.

Pfizer’s announcement of a near successful vaccine witnessed U.S. stock futures skyrocketed as investors cheered the news. Futures on the Dow Jones Industrial Average surged 1,646 points, implying an opening gain of more than 1,630 points. By late morning, the Dow was up more than 1,000 points, a rise of 3.7%.

Airline and cruise company stocks jumped in premarket trading — with some stocks rising by 20% and 30%. Both industries have been significantly affected by the global health crisis as travel restrictions and a resurgence in outbreaks continue to hurt demand.

Pfizer’s results were based on the first interim efficacy analysis conducted by an external and independent Data Monitoring Committee from the phase three clinical study. The independent group of experts oversees U.S. clinical trials to ensure the safety of participants.

The analysis evaluated 94 confirmed Covid-19 infections among the trial’s 43,538 participants. Pfizer and the U.S. pharmaceutical giant’s German biotech partner said the case split between vaccinated individuals and those who received a placebo indicated a vaccine efficacy rate of above 90% at seven days after the second dose.

It means that protection from Covid-19 is achieved 28 days after the initial vaccination, which consists of a two-dose schedule. The final vaccine efficacy percentage may vary, however, as safety and additional data continue to be collected.

All we can do is hope the company’s bad reputation is behind them and their greed a forgotten sin, however, if that fails let’s be more realistic and just hope the vaccine works.

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands