When did it become illegal to say where you’re from?

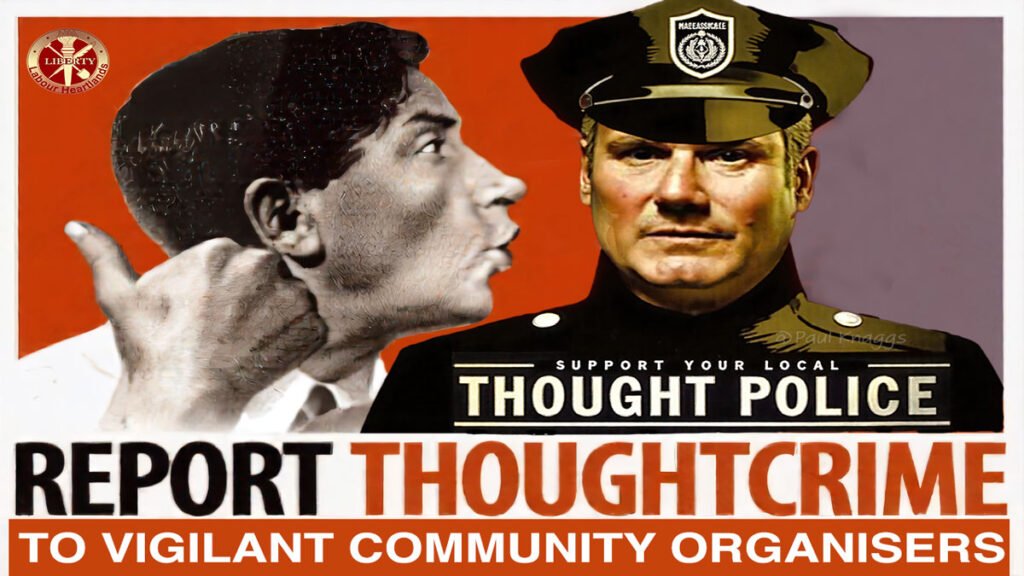

Welcome to the age of the Thought Police, where identity politics has swallowed common sense and even geography can get you cancelled.

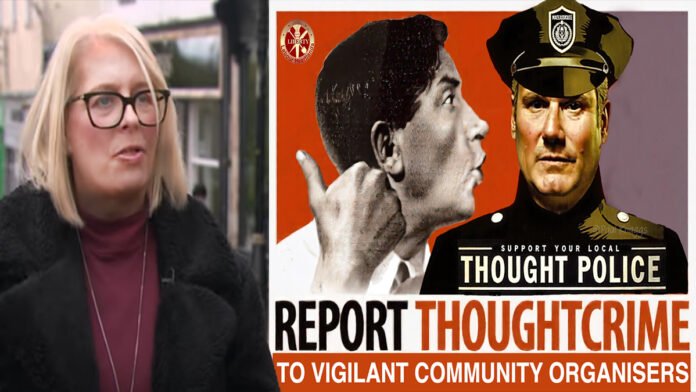

A councillor in Scotland is under police investigation for hate speech. Her crime? She said she was “born and bred here” during a television interview. That’s it. Three words. “Born and bred here.” For this supposedly inflammatory declaration of geographical origin, Claire Mackie-Brown, a Reform UK councillor, now faces a 22-page complaint to Police Scotland and the Ethical Standards Commissioner, plus calls for her suspension.

Let me be clear from the start. I’m not a member of Reform UK. I don’t share their politics on almost everything that matters; we’re on opposite sides. But as Voltaire’s principle reminds us, I will defend to my last breath her right to say she was ‘born and bred’ in her own town without facing criminal investigation. Because if we don’t defend free speech for those we disagree with, we don’t believe in free speech at all. We just believe in permission to speak, granted by those in power to those who say the right things.

The phrase “born and bred” has been part of the language of working people across these islands for generations. It means something real. It speaks of place, of community, of roots.

When a Yorkshireman says he’s “Yorkshire born and bred, strong in the arm and thick in the head,” he’s not inciting hatred against people from Lancashire, though he might be having a laugh at his own expense. When a Glaswegian says she’s born and bred in the Gorbals, she’s not declaring war on Edinburgh. When a Geordie says he’s born and bred in Newcastle, he’s not committing a hate crime against Sunderland (though they might argue the toss on that one).

Wait until they decide “woolly back” is a hate crime. Let’s see how the Scousers react when told they can no longer call their neighbours from the Wirral what they’ve been calling them for generations.

This is the madness of policing ordinary language. It’s not about kindness or inclusion. It’s about control. Once you criminalise the language of belonging, you erode identity itself. And when you strip people of the words that connect them to place, you’re not protecting anyone, you’re dismantling the very foundations of civil liberty.

And perhaps that’s exactly where we’ve arrived. In the new moral order, being from somewhere is suspect. Having roots is problematic. Attachment to place suggests you might value your community over abstract ideals of borderless humanity. The very notion that you might feel a particular connection to the town where you were born, where your parents and grandparents lived, where you know every street and remember every corner shop that closed down, is treated as inherently exclusionary. As if loving where you’re from means hating everyone who isn’t from there.

“As Orwell warned in Nineteen Eighty-Four, control of the past is control of the future. Deny people their history and you rob them of their future.” That’s precisely what’s happening here. When you criminalise the language of belonging, when you make it dangerous to say you’re from somewhere, you’re not protecting minorities or fighting hatred. You’re destroying the foundations of working-class identity. You’re obliterating people’s understanding of who they are and where they come from. You’re doing the work of those who have always wanted working people to forget their history, their solidarity, their power.

This is not progressive politics. This is the destruction of working-class identity dressed up in the language of social justice. Because working people, more than any other group, define themselves by place. Middle-class professionals are mobile, their identity tied to career and education and networks that span continents. But working people are rooted. They’re from somewhere specific. They’re born and bred. And when you criminalise that language, you criminalise them.

The irony is that the left, which once understood this intimately, has allowed itself to be dragged into policing the speech of ordinary people whilst the powerful continue to say whatever they like. When was the last time a billionaire faced investigation for inciting hatred? When did a property developer get reported to police for the violence of gentrification? When did a CEO face criminal charges for the hatred implicit in poverty wages? They don’t. Because this isn’t about protecting vulnerable people. It’s about controlling acceptable discourse. About ensuring that certain questions aren’t asked and certain grievances aren’t voiced.

Mackie-Brown apologised mid-interview, sensing that she’d crossed some invisible line. She shouldn’t have had to. There was nothing to apologise for. But that’s how the new censorship works. You don’t need formal laws against speech when you have an atmosphere of fear, where people self-censor because they’ve seen what happens to those who don’t. Where saying the wrong thing, or even the right thing in the wrong context, can bring the police to your door and 22-page complaints demanding your removal from office.

The complaint against Mackie-Brown is anonymous, which tells you everything you need to know about the courage of her accusers. They won’t even put their names to their outrage. They hide behind process, behind bureaucracy, behind the machinery of the state which they’ve weaponised to punish speech they dislike. This is not how free people resolve disagreements. This is how authoritarian societies crush dissent.

Now, some will say I’m defending the far right, that Reform UK doesn’t deserve the protections of free speech because they don’t respect it themselves. But this argument is poison. Either we have principles or we don’t. Either free speech applies to everyone or it applies to no one. The moment we decide that only the right sort of people deserve free speech, we’ve handed the weapon to whoever gets to define “the right sort of people.” And history teaches us that definition changes fast, and never in favour of the powerless.

The left has a proud tradition of defending free speech, even for fascists. In the 1930s, when Oswald Mosley’s Blackshirts marched through the East End, the left organised to stop them. Not through police complaints or demands for censorship, but through physical resistance and community solidarity. The Battle of Cable Street wasn’t won by filing ethics complaints. It was won by dockers and Jewish workers and Irish labourers standing together against hatred. They understood that you defeat bad ideas by confronting them, not by trying to make them illegal.

That tradition has been abandoned. Now, instead of argument we have bureaucracy. Instead of solidarity we have anonymous complaints. Instead of trusting working people to hear different views and make their own judgments, we treat them like children who must be protected from dangerous words. It’s insulting and it’s corrosive. It assumes that ordinary people can’t distinguish between someone saying they’re from a place and someone calling for violence. It treats democracy as a performance conducted under supervision, where only approved sentiments may be expressed.

The phrase “born and bred” belongs to working people. It’s ours. It speaks to lives lived in one place, to families who couldn’t afford to move, to communities built over generations. When middle-class professionals declare themselves “citizens of the world,” nobody investigates them for cosmopolitan elitism. But when working people say they’re from somewhere specific, suddenly it’s hate speech. This double standard is not accidental. It reflects who has power and who doesn’t, whose identity is acceptable and whose must be suppressed.

I don’t know what Mackie-Brown’s politics are beyond her party affiliation. I don’t know if she’s spent her life fighting for her community or if she’s just another politician on the make. It doesn’t matter. The principle is bigger than her. If saying you’re born and bred somewhere is now a criminal matter, then we’ve lost something fundamental. We’ve lost the right to belong. We’ve lost the right to have a home, not just in the physical sense but in the deeper sense of being from somewhere and being proud of it.

This is not about immigration. This is not about race. This is about whether working people are allowed to have an identity rooted in place without being criminalised for it. Whether you can love where you’re from without being accused of hating where others are from. Whether the basic vocabulary of community, the simple language of belonging, is still permitted in modern Britain.

Police Scotland should drop this investigation immediately. Not because Mackie-Brown is right about everything (she isn’t), but because she’s right about being born and bred where she’s from. That’s not a crime. That’s not hate speech. That’s just life. And if the authorities can’t tell the difference between someone stating a fact about their origins and someone inciting violence, then the authorities are the problem, not the speaker.

The left needs to remember what it once knew: that free speech is not a privilege granted to the deserving, but a right belonging to everyone. That you don’t defeat bad ideas by banning them, but by having better ones. That working people don’t need middle-class moral guardians deciding which words they’re allowed to use. That democracy means trusting the people to hear all views, even offensive ones, and make their own choices.

If we abandon these principles, if we let the state investigate people for saying they’re born and bred somewhere, we betray everything the labour movement fought for. Those who came before us didn’t win the right to organise, to strike, to speak, just so their grandchildren could hand those rights back to the state in exchange for protection from words that make them uncomfortable.

When saying where you’re from becomes a crime, the only criminals are those doing the investigating.

As Voltaire, or at least his biographer, famously put it: “I wholly disapprove of what you say, but will defend to the death your right to say it.”

The left and right can argue all day long, but on free speech we either stand together or fall separately. Once the state begins policing language, it will not stop at Reform councillors. It will come for journalists, activists, trade unionists, and yes, even you, for saying something as subversive as “born and bred.”

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands