Soldiers on both sides discovered each other’s reasons for fighting – by Matt Florence.

Operation Banner was the operational name for the British Armed Forces’ operation in Northern Ireland from 1969 to 2007, as part of the Troubles. It was the longest continuous deployment in British military history.

The British Army was initially deployed, at the request of the unionist government of Northern Ireland, in response to the August 1969 riots. Its role was to support the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and to assert the authority of the British government in Northern Ireland. This involved counter-insurgency and supporting the police in carrying out internal security duties such as guarding key points, mounting checkpoints and patrols, carrying out raids and searches, riot control and bomb disposal.

More than 300,000 soldiers served in Operation Banner. At the peak of the operation in the 1970s, about 21,000 British troops were deployed, most of them from Great Britain. As part of the operation, a new locally-recruited regiment was also formed: the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR).

The Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) waged a guerrilla campaign against the British military from 1970 to 1997.

Catholics welcomed the troops when they first arrived, because they saw the RUC as sectarian, but Catholic hostility to the British military’s deployment grew after incidents such as the Falls Curfew (1970), Operation Demetrius (1971) and Bloody Sunday (1972). In their efforts to defeat the IRA, there were incidents of collusion between British soldiers and Ulster loyalist paramilitaries.

From the late 1970s the British government adopted a policy of “Ulsterisation”, which meant giving a greater role to local forces: the UDR and RUC. After the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, the operation was gradually scaled down and the vast majority of British troops were withdrawn.

According to the Ministry of Defence, 1,441 serving British military personnel died in Operation Banner; 722 of whom were killed in paramilitary attacks, and 719 of whom died as a result of other causes. It suffered its greatest loss of life in the Warrenpoint ambush of 1979.

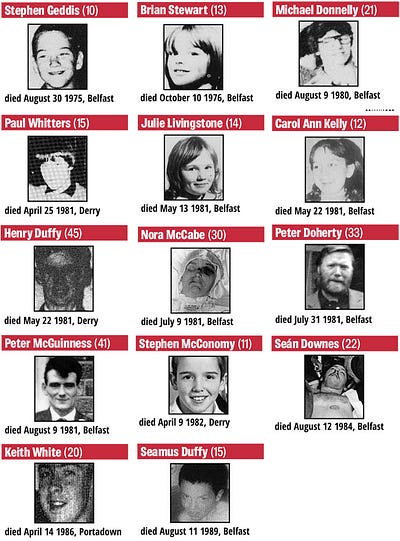

The British military killed 360 people during the operation, about 51% of whom were civilians and 42% of whom were members of republican paramilitaries, there are hundreds more estimated to have been killed due to British state collusion with loyalist paramilitaries.

The operation was gradually scaled down from 1998, after the Good Friday Agreement, when patrols were suspended and several military barracks closed or dismantled, even before the beginning of IRA’s decommissioning.

The process of demilitarisation started in 1994, after the first IRA ceasefire. From the second IRA ceasefire in 1997 until the first act of decommission of weapons in 2001, almost 50% of the army bases had been vacated or demolished along with surveillance sites and holding centers, while more than 100 cross-border roads were reopened.

Eventually in August 2005, it was announced that in response to the Provisional IRA declaration that its campaign was over, and in accordance with the Good Friday Agreement provisions, Operation Banner would end by 1 August 2007.

This involved troops based in Northern Ireland reduced to 5,000, and only for training purposes. Security was entirely transferred to the police.

The Northern Ireland resident battalions of the Royal Irish Regiment – which grew out of the Ulster Defence Regiment – were stood down on 1 September 2006. The operation officially ended at midnight on 31 July 2007, making it the longest continuous deployment in the British Army’s history, lasting over 37 years.

In October 2014, a small group of members of the British Veterans organization called ‘Veterans For Peace UK’ (VFP-UK) went on a 4 day journey across Northern Ireland to meet the people and communities where the British army had previously been deployed under operation banner.

These people included Republican prisoners of internment, ex-members of the provisional IRA, and victims of family members killed by the British Army in the infamous Bloody Sunday massacre of the 30th January 1972.

The 4 day journey was captured on camera and is available in the form of two 20 minute long videos on the ReelNews YouTube channel.

Former soldiers of the British Army reflect on meeting former members of the IRA in Derry, Northern Ireland, in a start to a process of reconciliation among men who had once been staunch enemies. The eight men who met agreed they should meet again, to continue telling their stories in an attempt to build a more trusting relationship

The VFP-UK Derry tour. This tour includes the VFP-UK visit to the Bloody Sunday museum, meeting relatives of people killed on the Bloody Sunday massacre of 1972, the site of the Battle of the Bogside, add interviews with civilians whose houses were raided by the British Army.

The veterans on the tour included former Royal Engineer Kieran Devlin, former Royal Marine Les Gibbons, former SAS soldier Ben Griffin. former Scots Guard Mike “Spike” Pike, a former soldier in the King’s Own Royal Border Regiment Kenny Williams, and former paratrooper Gus Hales. All had a variety of different reasons for joining the tour and being prepared to meet the other side but the most common reasons included finding closure while trying to find an understanding of the war they fought in and to find a lasting solution for peace in Ireland. “The idea is not to dwell too much in the past, for me it’s about moving forward” said former paratrooper Gus Hales.

The Derry and Belfast tours

The tour was split into two main cities, Derry and Belfast. The Derry tour included a tour of the Bloody Sunday museum, a meeting with relatives of civilians killed by the British Army on the Bloody Sunday massacre of 1972, the site of the Battle of the Bogside, and interviews with civilians whose houses were raided by the British Army.

The Belfast tour included a visit to see the “Peace Line” a wall seperating Catholic and Protestant neighbourhoods from each other. Interviews were filmed with Sinn Fein members and IRA veterans, the group also and a visit the hunger strikers museum.

One of the most striking things seen in the videos of the tours and the interviews between IRA and British Army veterans were the reasons for fighting.

The primary reason that the British Army veterans had for joining and fighting in the troubles was for adventure and the independence to see the world and escape from a life of boring work.

The primary reason given by IRA veterans however was that they were dragged into the war unwillingly when they themselves or their family were harassed or attacked by the British Army or by loyalists. During the VFP-UK tour of Belfast one IRA veteran called Pat Sheehan (now a Sinn Fein member of the Legislative Assembly) told the British Army veterans that he joined the youth wing of the IRA after Unionists fired bullets at his house in an attempt to scare his family into leaving the area.

Another IRA veteran told that he became involved in republicanism after British soldiers broke into his home and punched his mother in the face when he was a teenager.

A tribute to those unarmed citizens who died on 30 January 1972 at the hand of heavily armed Paras while protesting Internment. 36 years ago. ( This article was originally written and published by Matt Florence on Medium.com – Some pictures and text has been removed or rearranged to fit the format)

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands