“Every generation has to fight the same battles as every other. There’s no final victory and no final defeat. So everybody has to learn from what’s happened in the past and do the best they can…” -Tony Benn

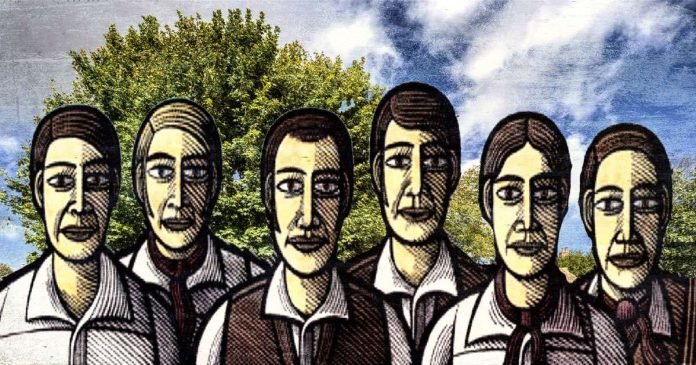

A Working Class Struggle

The stark differences between the 21st century and the early 19th century in the Western world are undeniable, and rightly so. If we fail to make progress over a span of more than 200 years, then any hope of true emancipation becomes a fading illusion. However, what remains a constant truth is that our working class struggles have undergone little transformation.

In both eras, we grapple with the pressing issues of wage cuts and a burgeoning cost of living crisis—a crisis that looms ominously, promising to worsen before any glimmer of improvement emerges.

The struggles endured by the Tolpuddle Martyrs find a chilling resonance in the present-day turmoil of our shared cost of living crisis.

Early 19th-century England was an era marked by a Great Transformation. The failure of the 1832 Reform Act to extend voting rights beyond property owners ignited a stirring amongst the people of Britain.

Influenced by ideas emanating from across the English Channel, where France had successfully cast off the yoke of monarchy and tyranny to establish a Republic, the working class of Britain felt the reverberations.

Many of them had fought in the Napoleonic wars, only to find themselves grappling with their own pressing cost of living crisis—a plight that undoubtedly left them feeling disenfranchised and marginalised.

It was the failure of the 1832 Reform Act that inspired the ideas of ‘The Chartist movement.’

In 1799 and 1800, the Combination Acts in the Kingdom of Great Britain outlawed “combining” or organising to gain better working conditions, passed by Parliament because of a political scare following the French Revolution.

In 1824, the Combination Acts were repealed due to their unpopularity and replaced with the Combinations of Workmen Act 1825, which legalised trade union organisations but severely restricted their activity.

By the start of the 19th century, the county of Dorset had become synonymous with poorly paid agricultural labour. In 1815, after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, 13% of the country’s population was receiving poor relief, and this worsened in the subsequent agricultural recession.

By 1830 conditions were so bad that large numbers of labourers joined the Swing Riots that affected southern England that autumn; more than forty disturbances occurred in the county, involving two thirds of the labouring population in some parishes.

Life as an English farmworker in the 1830s was dismal. Rent and a basic diet of tea, bread and potatoes would cost a typical family 13 shillings a week. But exploitative landowners, given land by the Enclosures, paid their workers as little.

A few landowners temporarily increased wages as a concession, but law enforcement was also increased and many labourers were arrested and imprisoned, and within a short time the gains in wages were reversed.

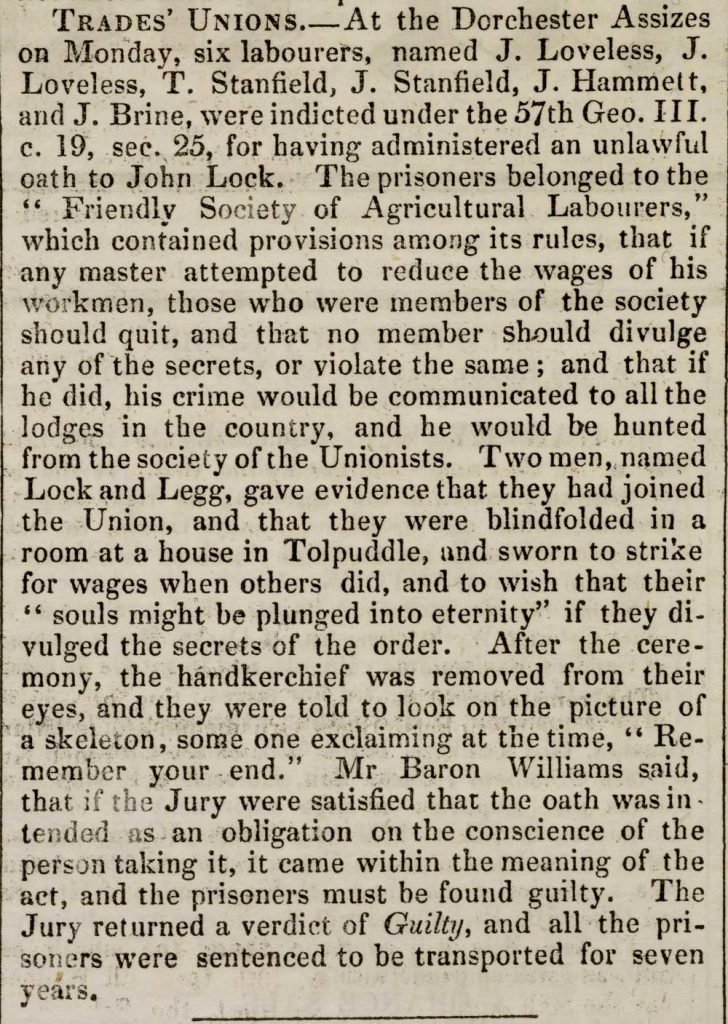

In the years 1833 and 1834, a great wave of trade union activity took place. Although at the time unions were lawful a lodge of the Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers was established. Entry into the union involved payment of a shilling (5p) and swearing before a picture of a skeleton never to tell anyone the union’s secrets.

It was created by George Loveless, a farm labourer, in response to his failed attempt to gain higher wages by negotiating with farmers and magistrates.

Membership of the society was subject to taking an oath of secrecy and using a password, which was changed every three months, in a similar way to that of the Freemasons.

That group of farm labourers from the village of Tolpuddle in Dorset, having seen their already low wages of 9 shillings a week cut to 7s.and then threatened with a further reduction decided to stand up collectively to oppose their exploitation.

These Tolpuddle labourers refused to work for less than 10 shillings a week, although by this time wages had been reduced to seven shillings and were due to be further reduced to six.

They used the basic principle of withdrawing their labour while negotiating a settlement through their collective action, today we would call this legitimate strike action.

In 1834, James Frampton, a magistrate and local landowner in Tolpuddle, wrote to Home Secretary Lord Melbourne to complain about the union, who recommended Frampton invoke the Unlawful Oaths Act 1797, an obscure law promulgated in response to the Spithead and Nore mutinies which prohibited the swearing of secret oaths.

The Whig government, alarmed at the dimensions of working-class discontent, arrested six Tolpuddle labourers—the Loveless brothers, James Brine, Thomas Stanfield and his son John, and James Hammett—ostensibly for administering unlawful oaths but actually for combining to protect their already meagre wages.

They were tried together before judge Sir John Williams in the case R v Lovelass and Others. All six were found guilty of swearing secret oaths and sentenced to transportation to Australia.

The Friendly Society’s rules show it was clearly structured as a friendly society that operated as a trade-specific benefit society, led by George Loveless, a Methodist local preacher, and meeting in the house of Thomas Standfield.

Groups such as the Friendly Society would often use a skeleton painting as part of their initiation process, where the newest member would be blindfolded and made to swear a secret oath of allegiance. The blindfold would then be removed and they would be presented with the skeleton painting to warn them of their own mortality but also to remind them of what happens to those who break their promises. An example of this skeleton painting is on display at the People’s History Museum in Manchester.

Find out more: https://t.co/aqz3Tf9zFl #SecretSociety #secretoath #tradeunion #skeletons #painting #HappyHalloween https://t.co/GxGzAkjjME

— People’s History Museum (PHM) (@PHMMcr) October 31, 2016

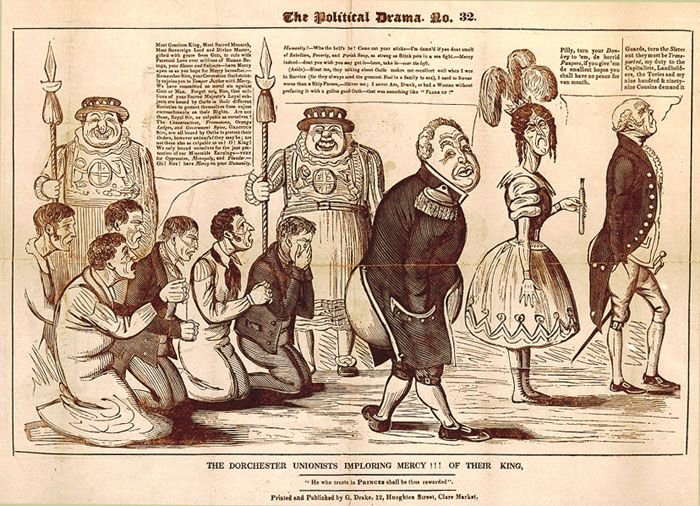

Convicted and sentenced by a hostile judge and jury, the six men became popular heroes.

They were tried together before Judge Sir John Williams in the case R v Lovelass and Others.

All six were found guilty of swearing secret oaths and sentenced to transportation to Australia.

When sentenced to seven years’ penal transportation, George Loveless wrote on a scrap of paper lines from the union hymn

“The Gathering of the Unions”:

God is our guide! from field, from wave,

From plough, from anvil, and from loom;

We come, our country's rights to save,

And speak a tyrant faction's doom:

We raise the watch-word liberty;

We will, we will, we will be free!

Unions organise to free the Tolpuddle Martyrs

Unknown to the six farm workers on the other side of the world, their case was being taken to Parliament and onto the streets of the capital.

As news of the sentence spread, the fledgling trade union movement began to organise a campaign for their release. On 24th March 1834, there was a Grand Meeting of the Working Classes, called by the Grand National Consolidated Trades Union on the instigation of Robert Owen. The meeting was attended by over 10,000 people: it was just the beginning. The agitation spread and grew. The London Central Dorchester Committee was formed to campaign for the men’s pardon.

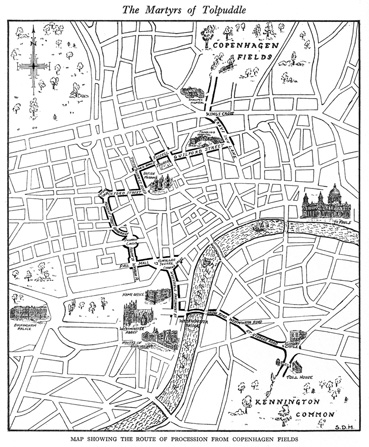

A vast demonstration took place on 21st April 1834. Up to 100,000 people assembled in Copenhagen Fields near King’s Cross. Fearing disorder, the Government took extraordinary precautions. Lifeguards, the Household Cavalry, detachments of Lancers, two troops of Dragoons, eight battalions of infantry and 29 pieces of ordnance or cannon were mustered. More than 5,000 special constables were sworn in. The city looked like an armed camp.

By 7am the protesters began to gather marshalled by trade union stewards on horseback. Robert Owen, the leader of the Grand Consolidated Union and the father of the Co-operative Movement arrived.

The grand procession with banners flying marched to Parliament in strict discipline. Loud cheers came from spectators lining the streets and crowding the rooftops.

At Whitehall, the petition, borne on the shoulders of twelve unionists, was taken to the office of the Home Secretary, Lord Melbourne. He hid behind his curtains and refused to accept the massive petition.

The Government tried to resist the mounting protest but the agitation for the men’s release was maintained. William Cobbett, Joseph Hume, Thomas Wakeley and other MPs kept the question constantly before Parliament. Petitions came from all over the country with over 800,000 signatures.

By June 1835, ten months after the Martyrs’ arrival in penal colonies, conditional pardons had been granted by Lord John Russell, the Home Secretary.

Russell had jumped the gun: legally, a convict could not be conditionally pardoned under four years. The flurry of correspondence between Whitehall and the Sydney and Hobart Government Houses caused confusion and delay.

Thomas Wakley’s campaign continued. He presented 16 petitions to Parliament. There was nationwide agitation. Conditional pardons were not good enough.

The Tolpuddle men refused to accept compromises and after further pressure, the Government agreed on 14th March 1836 that all the men should have a full and free pardon.

Trade unions had won and survived their first big challenge. The six farm workers from Tolpuddle were on their way home as free men.

England would see the birth of the labour movement a constant war against the oligarchy was to ensue.

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands