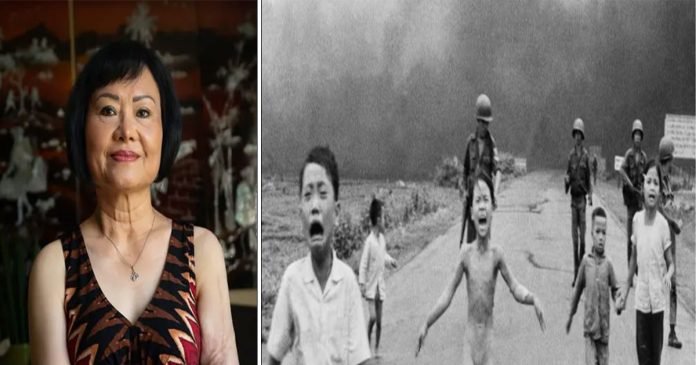

Vietnam ‘Napalm Girl’ receives final skin treatment in Florida 50 years after iconic image

Fifty years ago, Kim Phuc Phan Thi became internationally recognised after she was pictured running from a napalm bomb in 1972 in Vietnam.

Kim Phuc appeared in a Pulitzer Prize-winning photo she was nine-years-old at the time, running naked after a napalm attack in Vietnam on June 8, 1972. The photo was titled “The Terror of War” but it had become better known as “Napalm Girl.” It became a symbol of not just the Vietnam War, but the horrors of all wars.

Kim Phuc became known worldwide when she was pictured aged nine running down a road crying and naked, with burns across her body, after a napalm bomb was dropped on her village.

Phan Thi wrote for The New York Times, “I have only flashes of memories of that horrific day. I was playing with my cousins in the temple courtyard. The next moment, there was a plane swooping down close and a deafening noise. Then explosions and smoke and excruciating pain. I was 9 years old. Napalm sticks to you, no matter how fast you run, causing horrific burns and pain that last a lifetime.”

During a recent interview Phuc recounted the incident saying:“‘Well June 8th, 1972, I never forget’” She added, “I saw the aeroplane, and I saw four bombs landing like that and I heard the noise, and then suddenly, there was fire everywhere around me.”

“You’ve probably seen the photograph of me taken that day, running away from the explosions with the others — a naked child with outstretched arms, screaming in pain. Nick changed my life forever with that remarkable photograph. But he also saved my life. After he took the photo, he put his camera down, wrapped me in a blanket, and whisked me off to get medical attention. I am forever thankful,” she continued.

That little nine year old girl suffered severe injuries, with 65 percent of her body burned by Napalm, dropped indiscriminately on a Vietnamese village.

Napalm is an incendiary weapon—one that uses chemicals to produce heat and fire—that sticks to whatever it touches and causes severe, agonizing burns. When Harvard chemists invented it in 1942, they believed it would be used as a tool to burn down structures. In 1980, the United Nations banned the use of weapons like napalm against civilians, but these regulations don’t apply on the battlefield.

In the devastating photo, she is seen screaming and running out of the fire. The napalm had burned her clothes off. afterwards in an interview recalling the horror she stated: “We just kept running and running and running for a while,” she explained. “And I cried out ‘Too hot! Too hot!’ The soldiers tried to help me. They tried to pour the water over me, and at that moment, I lost consciousness.”

It was over a year later when Kim Phuc first saw the picture when she stated: “The first time I saw my picture, after 14 months being in hospital, oh my goodness. The first time I saw it, I said, ‘What!’ and ‘Why did he take my picture like that?’ I felt so ugly and ashamed because I was naked… I hated that picture … and I feel like, ‘Does anyone understand my pain?”

At the time, the photographer Nick Ut captured the image before he noticed how bad Thi’s burns were. “He put down the camera and took me to the nearest hospital, and I thought he saved my life,” Thi said. “I owe him. He’s my hero. Not only did he do his job as a photographer but also, he did extra as a human being. He helped. Now, I feel like he’s a part of my family. That’s why I call him Uncle Ut.”

Ut even went as far as to threaten the doctors, who claimed there was no space in the hospital for the injured children. When they told him to drive them to Saigon, he showed his press badge and said a picture of these kids will be in the newspapers the next day and “if one of them dies, you’ll be in trouble.”

I hated the photo when I first saw it because I was a little girl and I was naked and ugly, and I was so embarrassed. Ten years later, my story became hot news. The [communist] Vietnamese government rediscovered me. And all the journalists from other countries came to visit me, and I became a voice for propaganda … I [didn’t] belong to me anymore.

They thought I should be a war symbol for the state. At the beginning, I was happy because I was getting attention … but gradually, it interfered with my school schedule. The government took me out of school and asked me to work with them. They did not want to listen to me. At that time, I hated that picture. I did not want to be that little girl in the famous picture. I just thought the more that picture got famous, the more it would cost my private life.

In that time, there was so much hatred in me, bitterness. Sometimes, I thought of suicide because I thought, ‘After I die, I will not have to suffer.’ And remember, I still had a lot of physical pain.

The 59-year-old lives in Canada and has established the Kim Foundation, a non-profit organization that provides help to child victims of war around the world. She was named a United Nations goodwill ambassador in 1997 and wrote a book about her experiences. “Fire Road is a story of both unrelenting horror and unexpected hope, a harrowing tale of a life changed in an instant. Struggling to find answers in a world that only seemed to bring anguish, Kim ultimately discovers strength in someone who had suffered himself, transforming her tragedy into an unshakable faith,” as per the description.

The Kim Foundation International, an organization that provides medical assistance and psychological support to children affected by war. Today, she stands behind that famous photo and what it represents. “I am not a victim of war any more, I am a survivor. I feel like 50 years ago, I was a victim of war but 50 years later, I was a friend, a helper, a mother, a grandmother and a survivor calling out for peace.”

The photo won the Pulitzer Prize in 1973, a year after it was taken, four decades later, Ms Phuc, won the Dresden Prize in recognition of her work with UNESCO and children wounded in war.

In explaining why she was given the prize, the organisation said that for a long time Ms Phuc had wanted to escape her association with the picture, which reminded her constantly of the day everything changed for her.

The statement adds: “That is until Kim could bring herself to accept as her personal fate, that she cannot escape the photo. Until she understood that it represents rather a mandate directed to her; until she was able to see it as a gift.

“She became a goodwill ambassador for UNESCO, founded an organisation for children wounded and maimed in war, and speaks each year to thousands of people.

After receiving 12 laser treatments, Phuc’s scars are free of pain. she now says: “I am not longer a victim of war, I am not Napalm girl.” She now identifies as a friend, a helper, a mother, a grandmother and a survivor calling out for peace.

When asked about the war in Ukraine, she replied, “My heart is broken. My heart is broken for all people who lost their lives, especially children… My mom and I, we cry out every moment thinking what happened to me and my family 50 years ago.” During Thi’s own childhood, war destroyed their home and left her family destitute. “I had to deal with all the scars and the ugliness and the pain. Not just the deformity but the pain. Also, nightmares, traumatized, fearful.”

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands