Is Zarah Sultana working class? The question itself reveals how thoroughly modern politics has been emptied of material content…

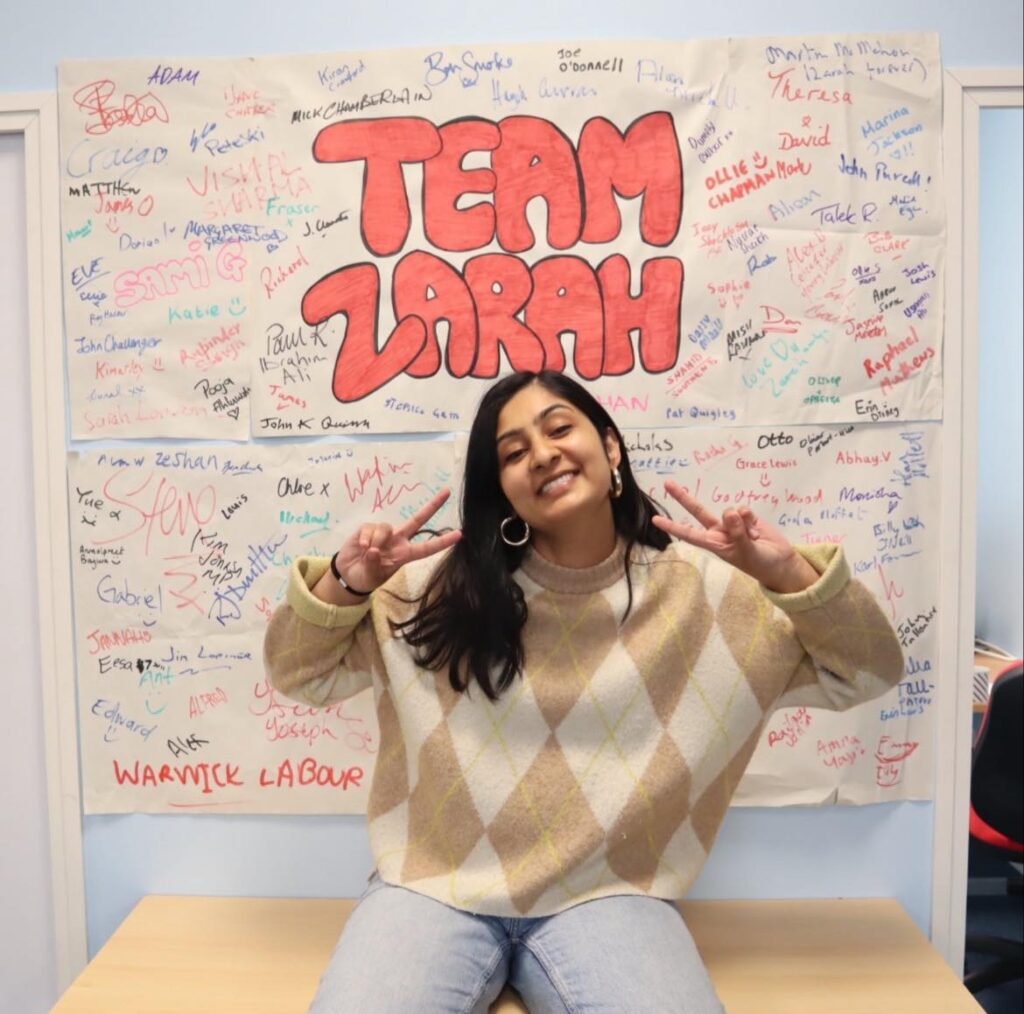

I was recently asked this question and realised I had never examined it closely. Like most who follow politics, I had grown accustomed to politicians from comfortable backgrounds speaking for working people. It is the norm, not the exception. But when you look at Sultana’s trajectory from Birmingham to the House of Commons, what emerges is not simply a question of class identity. It is a question about how the political class now manufactures itself.

The Facts of the Matter

Sultana was born in 1993 in Lozells, Birmingham. This much is indisputable, and it matters. Lozells sits within one of the most deprived constituencies in England. Perry Barr, which encompasses the area, ranks in the top 10% most deprived nationally. Birmingham itself is the seventh most deprived local authority in the country, with Lozells among its poorest wards. Nearly half of children in the ward live in low-income households.

Her grandfather migrated from Azad Kashmir in the 1960s to work in the West Midlands motor industry, part of that generation of South Asian workers who built post-war Britain while being told they didn’t belong in it. This is authentic working-class heritage, the kind that runs in the blood. The question is what happened to it in the next generation.

Sultana’s father worked as an accountant at the University of Central England, now Birmingham City University. Her mother kept the home. Both were Labour Party members. By any honest reckoning, this is middle-class life. An accountant at a university is a professional, requiring qualifications, providing stability, pension contributions, and a degree of social standing that separates it entirely from the shop floor or the warehouse. These are not trivial distinctions. They are the material differences that shape how children grow up and what futures they can imagine.

She attended Holte Visual and Performing Arts College, a non-selective comprehensive, before moving to King Edward VI Handsworth Grammar School for sixth form. This transition deserves attention. The King Edward VI grammar schools in Birmingham are selective, highly competitive institutions requiring entrance examinations. Gaining entry for sixth form demands academic distinction. She then went to the University of Birmingham, a Russell Group institution, graduating with first-class honours in International Relations and Economics.

During her studies, Sultana worked retail jobs at Primark and H&M. She has cited this experience repeatedly as evidence of working-class credentials. It is true as far as it goes, but part-time retail work during university is not the same as retail work as a career or a necessity. Millions of students work similar jobs. It does not make them working class any more than a banker’s son washing dishes during his gap year becomes proletarian. The work is real; the class position it confers is not.

The Pipeline

Here is where the story becomes interesting. Sultana’s path to Parliament follows a now-familiar trajectory that has little to do with class and everything to do with the professionalisation of politics.

The Career Ladder Nobody Admits Exists…

What follows is where the story becomes instructive. Sultana’s path to Parliament follows a trajectory that has become so familiar it might as well be printed on a flowchart and handed out at fresher’s week.

By 2014, while still at university, she was elected to the National Executive Council of the National Union of Students and to the National Committee of Young Labour. These are not casual extracurricular activities. They are the staging posts of the political class, the places where ambitious students learn the language and habits of power. Wes Streeting, now Health Secretary, followed precisely this route: Cambridge Students’ Union President, then NUS President, then Progress, then council, then Parliament. The conveyor belt runs smoothly.

After graduation, Sultana moved to the voluntary sector, working as a Marketing and Engagement Officer for Muslim Engagement and Development (MEND), an anti-Islamophobia campaign group. By June 2018, she had advanced to Parliamentary Officer, a role involving lobbying, drafting briefings, and engaging with legislators. This is quintessential political class employment, bridging activism and the legislature, requiring high cultural capital and providing access to networks of power that most working people will never glimpse.

She then became a Community Organiser for Labour’s Community Organising Unit in the West Midlands. Corbyn established this unit in 2018 to build grassroots support. The title sounds appealingly grassroots, but the reality was a paid political staffer role within the party apparatus, increasingly seen as a stepping stone for Corbyn-aligned candidates to secure parliamentary selections.

In 2019, Sultana was placed fifth on Labour’s European Parliament list for the West Midlands. She was not elected, as Labour won only one seat. Later that year, when Jim Cunningham announced he would not contest Coventry South, she was selected as the Labour candidate with backing from Unite, Momentum, the Fire Brigades Union, and the Communication Workers Union. She won by 401 votes.

Sultana was appointed Parliamentary Private Secretary to Dan Carden, then Shadow Secretary of State for International Development, in January 2020. Both sat in the Socialist Campaign Group. Both were Corbyn loyalists. Yet their paths would diverge in ways that expose the fundamental fault line now fracturing the British left. By 2025, Carden had become leader of the Blue Labour parliamentary caucus, embracing what he calls a shift ‘from left to left’ that prioritises socially conservative positions on immigration and cultural values to reconnect with working-class voters who feel abandoned by progressive liberalism.

Sultana chose the opposite path. When Adnan Hussain, a fellow Independent Alliance MP, stated that trans women are ‘not biologically women’ and advocated for segregated ‘safe third spaces’, her response was categorical: ‘Trans rights are human rights. Your Party will defend them, no ifs, no buts. Anyone who feels like they can’t subscribe to these principles, then Your Party might not be for them. Bigotry has no place in it.’

This is not socialism. It is liberalism in a red dress, and it exposes the manufactured politician’s fatal flaw. Sultana and Carden emerged from identical circumstances: the same left tradition, the same political structures, the same pathway through student politics to Parliament. Both claim to speak for working people. Yet when confronted with the actual beliefs of millions of working-class voters, culturally conservative, economically left-wing, deeply sceptical of liberal social orthodoxies, they chose opposite responses. Carden moved toward those voters. Sultana moved to exclude them.

A genuine socialist movement would welcome all who oppose austerity and monopoly capitalism, whether they are culturally liberal or socially conservative, so long as they stand against exploitation. Its task is to build bridges across difference, not burn them in the name of purity. Sultana’s version offers the opposite: an exclusive club where membership requires not solidarity in the fight against capital, but loyalty to progressive social positions that millions of working-class people do not share and never will.

The irony is exquisite. Two politicians manufactured by the same system, shaped by the same structures, fluent in the same language of class struggle, arrive at fundamentally incompatible conclusions about what working-class politics requires. The road to Westminster did not determine their destinations. But it ensured that neither would understand the terrain well enough to find a path that actually leads somewhere working people want to go.

The Toolmaker’s Son Revisited

We have been here before. Labour Heartlands has examined Keir Starmer’s invocation of his toolmaker father, a claim made so frequently that audiences now laugh when he repeats it. The deeper issue is not frequency but accuracy. Starmer’s father owned the Oxted Tool Co., operating from a rented workshop on an industrial estate. He was a skilled self-employed tradesman, not a factory worker under the thumb of managers. As Rodney Starmer himself wrote in a 2014 newsletter, his son spent six months before university working ‘in my factory operating a production machine’.

This is not dishonesty in the crude sense. It is something more insidious: the careful curation of biographical details to construct an image of working-class authenticity that does not quite match the material reality. Starmer attended Reigate Grammar School (which became fee-paying during his time there), Oxford, and became a barrister and Director of Public Prosecutions. His background was petit bourgeois, not working class.

Sultana’s case follows the same pattern. Growing up in a deprived neighbourhood is not the same as growing up deprived. A university accountant’s household in Lozells is materially different from a warehouse worker’s household in the same postcode. The geography is working class. The family circumstances were not.

The Infrastructure of Manufacture

The pipeline to Parliament does not run on accident. It runs on money, organisation, and a ruthless understanding of how power reproduces itself.

In the 1990s, Progress served this function for New Labour. Founded by Derek Draper, Peter Mandelson’s aide, it was structured as a company limited by guarantee. Its purpose was to train parliamentary candidates, promote its own ideological mould, and ensure that Blair’s project had the right kind of people in the right kind of seats. Between 1996 and 2013, it raised 122 times more funding than any other Labour members’ association. When Len McCluskey accused it of manipulating selection procedures, Progress responded with the bland assurance that it merely helped “train and mentor candidates”, to whom it did not give money directly. The details, it insisted, were “plainly explained”. Anyone who has watched how power operates in Britain will recognise that particular formulation.

Labour Together represents the evolution of this machinery, refined for a new era. Founded in 2017, ostensibly to bring the party together after the Brexit referendum, it operated as what one careful observer calls “a ruthless, factional grouping which aimed to use any means necessary to delegitimise and destroy Jeremy Corbyn”. Between 2017 and 2020, the organisation received an estimated £849,000, principally from hedge fund manager Martin Taylor and businessman Trevor Chinn.

These donations were not declared as required by law until after Starmer won the leadership. The Electoral Commission subsequently fined Labour Together £14,250 for over twenty breaches of electoral law. Morgan McSweeney, the organisation’s director, claimed an “admin error”. The effect, whatever the cause, was to conceal the organisation’s funding and political alignment throughout the crucial period when it was working to shape Labour’s future. One might call this convenient. One would be understating the case.

McSweeney subsequently devised the candidate selection process that locked the left out of Parliament. Under his system, party headquarters retained control of the crucial longlisting stage, the point at which inconvenient candidates could be quietly filtered out before members ever saw them. The result has been well documented, though it bears repeating. Respected left-wing MPs like Beth Winter were deselected from safe seats. Candidates like Faiza Shaheen were removed at the last moment, sometimes for infractions as serious as liking tweets by Nicola Sturgeon. Councillors who had served their communities for years were blocked for similar thought crimes.

Meanwhile, Labour Together associates were parachuted into constituencies with the efficiency of a military operation. Josh Simons, who replaced McSweeney as director, now sits as MP for Makerfield. Luke Akehurst, the NEC factional enforcer whose primary qualification appears to be unwavering loyalty to the machine, was handed Durham. McSweeney’s own wife, Imogen Walker, was found a seat in Hamilton and Clyde Valley, winning the selection against a local candidate by seven votes. The decisive margin came from online voting rather than the hustings, where members might have asked awkward questions about her qualifications beyond marriage to the right person.

More than £300,000 in staffing costs and secondments flowed from Labour Together to shadow cabinet members including Rachel Reeves, David Lammy, and Yvette Cooper. This is how you build a political class: not through open competition or democratic selection, but through careful placement of loyalists in positions where they can elevate more loyalists.

The pattern is unmistakable. Progress trained candidates for Blair’s project. Labour Together manufactured them for Starmer’s. Both operated with substantial private funding from wealthy donors, minimal transparency, and systematic exclusion of those who did not fit the approved mould. The difference is one of scale and sophistication. Progress merely influenced selections. Labour Together captured the selection machinery itself, ensuring that only approved products emerge from the process, tested for ideological purity and personal loyalty before members ever see their names on a ballot.

The question of whether politicians are shaped by the road they take or take the road to reach their destination becomes academic when the road itself is privately owned and operated by a single faction. What we are witnessing is not the democratisation of politics but its opposite: the creation of a professional political class that reproduces itself through institutional control, wealthy patronage, and the systematic exclusion of anyone who might genuinely challenge the economic settlement that has governed Britain since Thatcher.

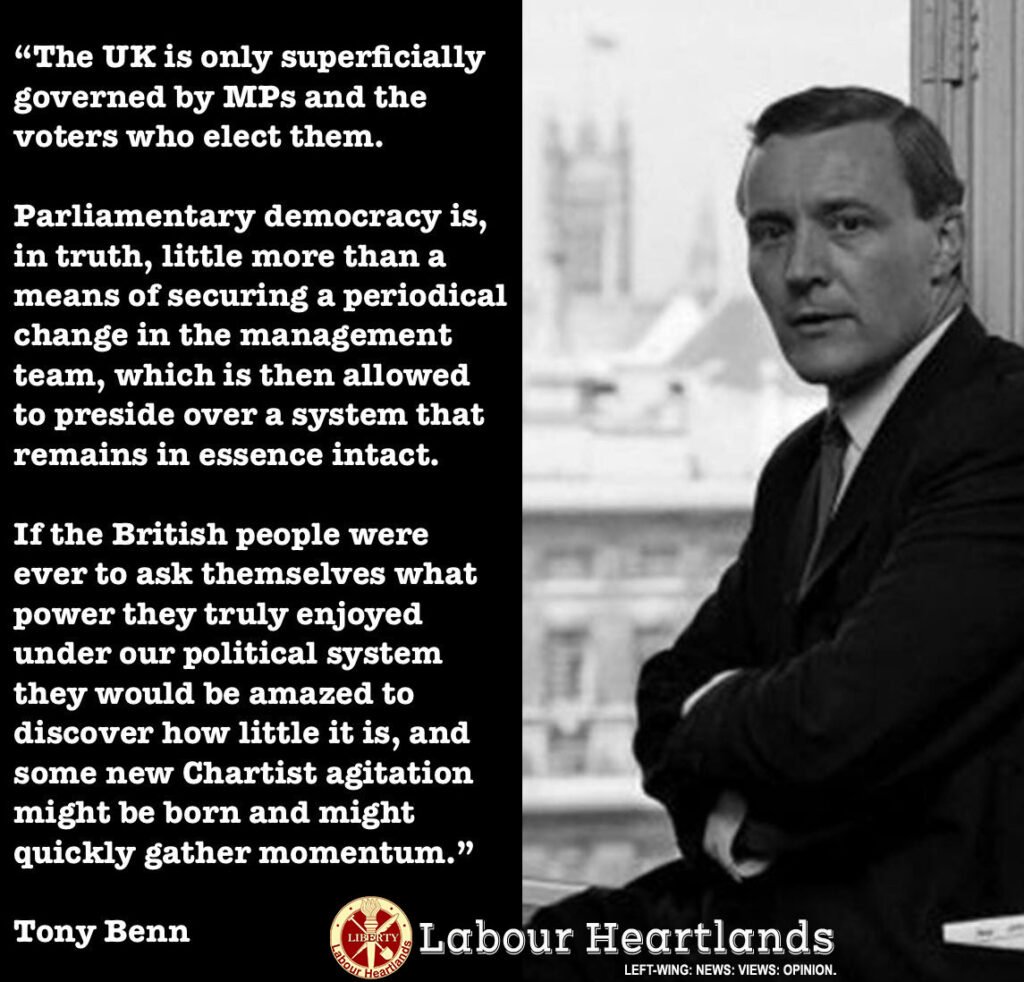

What Tony Benn Understood

None of this suggests that Sultana cannot speak about inequality or represent working people politically. Tony Benn, that great advocate for the working class, was the son of a Viscount. He rode that particular horse very well indeed. Class origin does not determine political alignment, and anyone who claims otherwise has not been paying attention to history.

But Benn was honest about where he came from. He did not claim to have grown up in poverty or to understand the working-class experience from the inside. He argued for working-class interests from a position of acknowledged privilege, which gave his advocacy a certain integrity. He understood what Orwell understood: that the question is not whether you were born in a miner’s cottage but whether you stand with the miners when the pit closes.

The more troubling question is whether the pathway matters at all. The trajectory from student activism to NUS to NGO to party apparatus to Parliament has become so common that Parliament’s own research notes it plainly: ‘the past 20 to 30 years have also seen changes in the professional background of MPs, with increasing numbers having worked as MPs’ staff, ministerial special advisers or think-tank policymakers before running for elected office.’

This is not a left-right distinction. Ed Miliband, Matt Hancock, and Oliver Dowden all served as special advisers before election. David Cameron was a SpAd in the early 1990s. The political class has become a profession with its own career ladder, entry requirements, and internal logic. Whether one starts on the left or right of this ladder, one is still on it, and the view from up there looks remarkably similar regardless of the party rosette.

Product or Pilgrim?

Here lies the essential question: are these people products of the road they have taken, or did they take the road to reach their destination? The answer, uncomfortable as it may be, is both.

The System’s Children…

Someone who enters the NUS ecosystem, advances through NGO work, and lands in the party apparatus has been shaped by that journey. They have learned to speak in certain ways, to frame issues according to certain logics, to network with certain people. By the time they reach Parliament, they are creatures of the system they navigated. Their views, insofar as they are sincere, have been formed within that system’s boundaries. They may rage against injustice, but it will be the kind of injustice the system permits them to see.

But they also chose that path. No one compelled Sultana to join the NUS executive or work for MEND or become a community organiser. Each step was a decision toward a political career, made with eyes open. The road shaped her, certainly, but she selected the road. This is not an accusation. It is an observation about how power reproduces itself in a society that claims to be democratic.

The more troubling question is whether this system can produce politicians capable of genuinely challenging the structures they climbed through. Can someone whose entire adult life has been spent in the political ecosystem see clearly enough to dismantle the inequities that ecosystem protects? Or does the journey necessarily produce defenders of the route they took, whatever their stated ideology? These are not rhetorical questions. They go to the heart of why our politics feels so disconnected from the lives of ordinary people.

The Verdict on Sultana

Zarah Sultana is best understood as what some sociologists call the ‘graduate precariat’ or ‘radicalised middle class’. She possesses the educational credentials and cultural capital of the middle class. Her retail work, while real, was typical university employment rather than a defining life circumstance. Her professional career before Parliament was entirely within the political and NGO sectors, the kind of work that exists in a peculiar ecosystem of grants, campaigns, and institutional lobbying.

That she grew up in Lozells is meaningful. That her grandfather worked in the motor industry is part of a genuine working-class heritage, the kind that should matter more than it does in our public life. But her immediate family circumstances, educational trajectory, and career path place her firmly in the “professionalised political class” that has increasingly colonised Parliament like Japanese knotweed in a garden.

Does it matter? It matters if we believe that who governs should reflect who is governed. It matters if we think lived experience shapes political judgment in ways that theory cannot replace. It matters if we notice that the routes to Parliament are narrowing even as the rhetoric of representation broadens, creating an ever-smaller gene pool from which our supposed representatives are drawn.

The problem is not that Sultana is not working class. The problem is that the system through which she rose ensures that almost nobody who reaches Parliament will be. The pipeline produces a certain kind of politician, one fluent in the language of class struggle but formed entirely within the structures of professional politics. They can speak about inequality with great passion. Whether they can see it clearly enough to fight it is another question entirely.

The Real Question

Perhaps the question is not whether Zarah Sultana is working class. Perhaps it is whether a Parliament of Barristers and manufactured politicians, drawn from an ever-narrowing slice of professional experience, can ever truly serve working people. The answer, I fear, is written in every broken promise and abandoned community across this country.

Of course, it would be dishonest to conclude without acknowledging the elephant in the room. Jeremy Corbyn himself represents the same manufactured trajectory, though an earlier generation’s version. He is the middle-class son of middle-class parents, a man who studied Benn’s politics without inheriting his clarity. Corbyn has become less a voice for the working class and more a trumpet for progressive liberals, a politician of all seasons except the harsh, cold winter of working-class Britain. He can speak passionately about Palestine and trans rights, but grows noticeably quieter when the conversation turns to immigration’s impact on wages or women’s sex-based rights. The student learned the rhetoric but missed the lesson.

The Illusion

Tony Benn warned that without true democracy, we become “spectators of our fate, rather than active participants.” The manufactured political class has achieved precisely this transformation.

They got their power from party machinery, not from popular consent. They exercise it in the interests of the factions that elevated them, not the communities they claim to represent. They are accountable to selection committees and factional bosses, not to working people. And we cannot get rid of them, because the pipeline ensures that only approved replacements will follow. Ask Benn’s five questions of any MP manufactured by the Labour Together system, and you will discover that not one can be answered democratically.

But perhaps this is the point. Perhaps the manufacturing of politicians is not a corruption of British democracy but its natural state. Benn understood this better than most: “I don’t think people realise how the establishment became established. It simply stole the land and property off the poor, surrounded themselves with weak-minded sycophants for protection, gave themselves titles and have been wielding power ever since.”

The pathway from student politics to Parliament is simply the modern mechanism for an ancient process. Selection committees have replaced hereditary titles. Party apparatus has replaced land ownership. Ideological conformity has replaced aristocratic breeding. But the function remains identical: to ensure that power reproduces itself in the hands of a narrow class, while maintaining the illusion of democratic choice. No one with power likes democracy, which is precisely why every generation must struggle not to keep it, but to win it for the first time. Including you and me, here and now.

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands