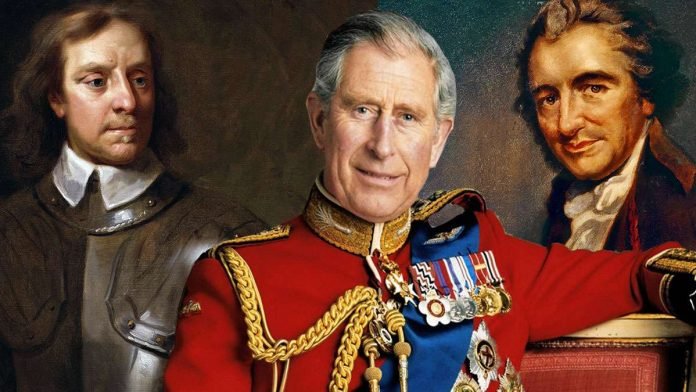

Long Live the King. Long live the Republic.

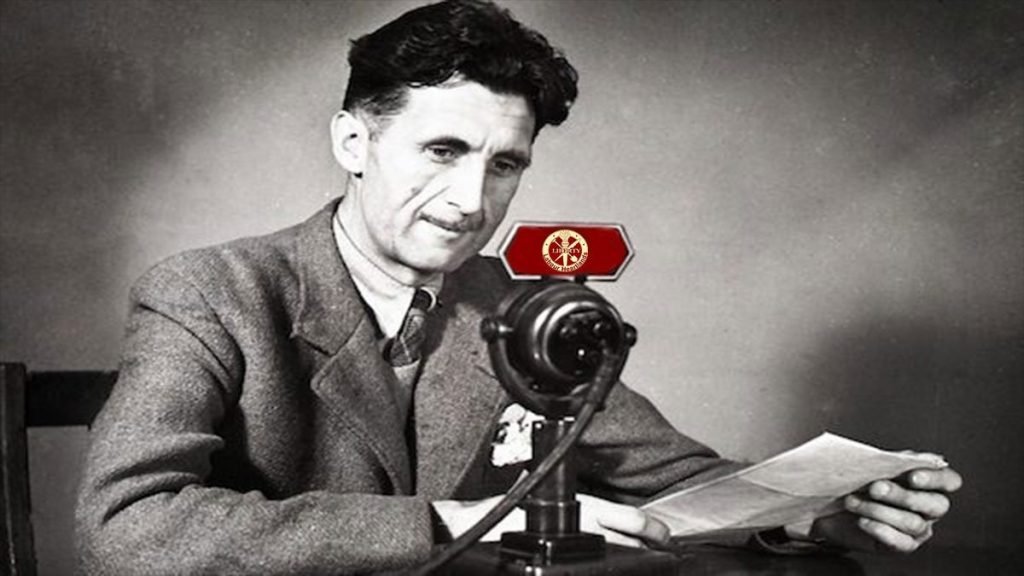

George Orwell once remarked that an English intellectual would rather be caught stealing from the poorbox than be seen standing to attention for God Save the King. Well, it seems those intellectuals have finally found something they value even less: their principles.

As King Charles III ascended to the throne amidst pomp and circumstance, the calls for a republic fell silent, drowned out by the sycophantic cheers of the elites. Meanwhile, the working class was left to fend for itself, struggling for a living wage and barricading their doors against the energy bailiffs. But fear not, for at least they were all treated to a nice slice of cake at the royal banquet.

The perennial pendulum of the republic versus monarchy debate has ceaselessly swung, captivating minds with the allure of a constitutional transformation. Yet, looming over the discourse like a spectre is the chilling prospect of figures such as President Blair or President Johnson, a notion that has consistently served as the most compelling counterargument to upending the status quo. In the following exploration, we shall delve into a selection of historical arguments that have shaped this ongoing deliberation.

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense

Thomas Paine was an English-born American political activist, philosopher, political theorist, and revolutionary. He authored Common Sense (1776) and The American Crisis (1776–1783), the two most influential pamphlets at the start of the American Revolution, and helped inspire the colonist in 1776 to declare independence from Great Britain. His ideas reflected Enlightenment-era, ideals of transnational human rights.

His arguments for a Republic and against hereditary succession relied on common sense.

Common Sense is a 47-page pamphlet written by Thomas Paine in 1775–1776 advocating independence from Great Britain to people in the Thirteen Colonies. Writing in clear and persuasive prose, Paine marshalled moral and political arguments to encourage common people in the Colonies to fight for egalitarian government. It was published anonymously on January 10, 1776, at the beginning of the American Revolution and became an immediate sensation.

It was sold and distributed widely and read aloud at taverns and meeting places. In proportion to the population of the colonies at that time (2.5 million), it had the largest sale and circulation of any book published in American history.

It was radical because its arguments made sense common sense but more so it helped the people understand the system of

It ultimately helped ignite the American Revolution. Paine argued that the monarchy was evil and should be rejected as a form of government. To underscore his point in an age of Religion, he cited the Bible to argue his case — in Judges 8:22-23: “The Israelites said to Gideon, ‘Rule over us, you and your son and your grandson….’ Gideon told them, ‘I will not rule over you. The LORD will rule over you’

But the main thrust was to understand the system people lived under and how far removed from democracy that system was.

Of Monarchy and Hereditary Succession

Mankind being originally equals in the order of creation, the equality could only be destroyed by some subsequent circumstance; the distinctions of rich, and poor, may in a great measure be accounted for, and that without having recourse to the harsh, ill-sounding names of oppression and avarice. Oppression is often the CONSEQUENCE, but seldom or never the MEANS of riches; and though avarice will preserve a man from being necessitously poor, it generally makes him too timorous to be wealthy.

But there is another and greater distinction, for which no truly natural or religious reason can be assigned, and that is, the distinction of men into KINGS and SUBJECTS. Male and female are the distinctions of nature, good and bad the distinctions of heaven; but how a race of men came into the world so exalted above the rest, and distinguished like some new species, is worth inquiring into, and whether they are the means of happiness or of misery to mankind.

In the early ages of the world, according to the scripture chronology, there were no kings; the consequence of which was, there were no wars; it is the pride of kings which throw mankind into confusion. Holland without a king hath enjoyed more peace for this last century than any of the monarchial governments in Europe. Antiquity favours the same remark; for the quiet and rural lives of the first patriarchs hath a happy something in them, which vanishes away when we come to the history of Jewish royalty.

Government by kings was first introduced into the world by the Heathens, from whom the children of Israel copied the custom. It was the most prosperous invention the Devil ever set on foot for the promotion of idolatry. The Heathens paid divine honours to their deceased kings, and the Christian world hath improved on the plan, by doing the same to their living ones. How impious is the title of sacred majesty applied to a worm, who in the midst of his splendor is crumbling into dust!

As the exalting one man so greatly above the rest cannot be justified on the equal rights of nature, so neither can it be defended on the authority of scripture; for the will of the Almighty, as declared by Gideon and the prophet Samuel, expressly disapproves of government by kings. All anti-monarchical parts of scripture have been very smoothly glossed over in monarchical governments, but they undoubtedly merit the attention of countries which have their governments yet to form. RENDER UNTO CAESAR THE THINGS WHICH ARE CAESAR’S is the scripture doctrine of courts, yet it is no support of monarchical government, for the Jews at that time were without a king, and in a state of vassalage to the Romans.

Now three thousand years passed away from the Mosaic account of the creation, till the Jews under a national delusion requested a king. Till then their form of government (except in extraordinary cases, where the Almighty interposed) was a kind of republic administered by a judge and the elders of the tribes. Kings they had none, and it was held sinful to acknowledge any being under that title but the Lord of Hosts. And when a man seriously reflects on the idolatrous homage which is paid to the persons of kings, he need not wonder that the Almighty, ever jealous of his honour, should disapprove of a form of government which so impiously invades the prerogative of heaven.

Rights of Man: Thomas Paine on the absurdity of a hereditary monarchy (1791)

After having helped the American colonists shake off their reluctance to secede from the British Empire, Thomas Paine (1737-1809) turned his attention to the French Revolution which he vigorously defended against attacks by Edmund Burke. In the Rights of Man (1791) he distinguished between two types of government – the “representative” which was flourishing in North America, and the “hereditary” which still prevailed in Britain and France. He had the following harsh things to say about having a hereditary monarch:

We have heard the Rights of Man called a levelling system; but the only system to which the word levelling is truly applicable, is the hereditary monarchical system. It is a system of mental levelling. It indiscriminately admits every species of character to the same authority. Vice and virtue, ignorance and wisdom, in short, every quality, good or bad, is put on the same level. Kings succeed each other, not as rationals, but as animals. It signifies not what their mental or moral characters are. Can we then be surprised at the abject state of the human mind in monarchical countries, when the government itself is formed on such an abject levelling system?—It has no fixed character. To-day it is one thing; to-morrow it is something else. It changes with the temper of every succeeding individual, and is subject to all the varieties of each. It is government through the medium of passions and accidents. It appears under all the various characters of childhood, decrepitude, dotage, a thing at nurse, in leading-strings, or in crutches. It reverses the wholesome order of nature. It occasionally puts children over men, and the conceits of non-age over wisdom and experience. In short, we cannot conceive a more ridiculous figure of government, than hereditary succession, in all its cases, presents.

The evil of hereditary succession is more pressing a concern than its absurdity—the practice lends itself to oppression. Men who consider themselves born monarchs easily grow insolent and become disconnected from the interests of ordinary people. This actually renders them dangerously ignorant and unfit to rule.

-Thomas Paine

The pageantry of royal events does not hide some of its most unappealing aspects, namely, its disregard for the notion of the equal and inalienable rights of man, the idea that political sovereignty can be passed down from one generation to the next through a bloodline, and that any “legitimate” sovereign has an equal right to that political power regardless of their skills, capacities, or moral character. One of the great critics of hereditary monarchical power was Thomas Paine who had the luxury or the bad luck to be involved in two of the great world revolutions, the American and then the French. In this passage he turns a major criticism of revolution levelled by its conservative critics, like Edmuch Burke, on its head. Perhaps with a conscious reference to the “Levellers” of the English Revolution of the mid-17th century, Paine says that to call the idea of the “rights of man” a “levelling system” in which the good and the mighty are brought down to some low common denominator of the people is itself a form of “levelling” which in his view is unjustified. Paine thought the “levelling” came from the other direction, that anybody, no matter how well or badly qualified for the position of monarch they were, could become a king so long as the proprieties of bloodline, descent, and family connections were adhered to. Thus all qualifications were “levelled” in the name of an ancestral claim to political power. This is a major reason why Paine called “hereditary monarchy” the most “ridiculous figure of government” imaginable.

A summary of the UK government through time

- At the start of the Middle Ages, England was ruled by a king. The institution which came to be called Parliament was just beginning.

- In the 17th century, war broke out between King James II of England and Parliament, ending in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. This established a constitutional monarchy, which is a ‘king-controlled-by-parliament’ but the reality was that middle and labouring classes still had very little say in politics and still did not have the vote. The King and the upper classes remained in control.

- The 19th century saw the political world begin to change. Some working people resented new machines replacing their labour and in 1811-12 there was a widespread outbreak of machine breaking by hundreds of workers known as Luddites.

- In 1819 a mass meeting in St. Peter’s Fields, Manchester, (Peterloo Massacre) turned violent when militia drew their swords to clear a gathering of middle and working class workers and their families calling for voting reform and a free press. Magistrates had deemed the reform illegal.

- By 1832 a reform of Parliament began and a number of acts of Parliament were passed giving the vote to a further 400,000 people. However, this was mostly just the middle classes. chartist

- Britain did not become a democracy until the Representation of the People Acts of 1918 and 1928 that gave the vote to all men and women over the age of 21.

Some historians in the 19th and early 20th centuries saw British history as an inevitable progression – from tyranny and monarchy to constitutional monarchy and democracy.

Modern historians do not see this as inevitable any more. They think the people of the time were not building democracy – they were just seeking solutions to the problems of the time. It is nevertheless true that, through time, Britain changed from a feudal monarchy to a resemblance of democracy.

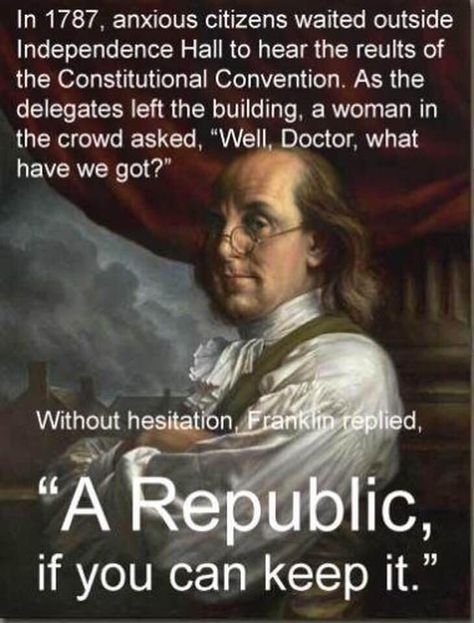

So the question stands ‘A Republic if You Can Get It?

The Queen is dead, long live ‘The Republic’

For the people that want to see the monarchy abolished and replaced with an elected, democratic head of state acting as a counter to government, a government within an overwhelmingly Tory majority, they must realise they are demanding the biggest constitutional shake-up since the English civil war that created just a whisper of a Republic.

The Interregnum is the period between a monarchy and a Republic. Only a concerted articulate campaign ‘now’ would stand a chance of changing the status quo otherwise the title will pass unhindered as it’s done almost uninterrupted for near on a thousand years to the next in line.

Any transformation to a republic would need to start with a Parliament willing to make that transformation, more so a party willing to make that transformation without using the case for a Republic as cover to steal away our liberties and give themselves greater power.

The next natural step would be the transformation of the House of Lords to a democratically elected house. The likelihood that the majority would vote away their own power is very unlikely and only a manifesto promise and a referendum on the HOL would be enough.

There is not one major or minor party in the UK willing to rock the status quo, to be frank, the major parties are not there not to challenge the system, they are part and parcel of the establishment, the acceptable face of an illusion of democracy.

The abolition of the monarchy could only come if there was a political Party willing to carry that in its manifesto and to be frank that will never happen.

Although Sir Keir Starmer once declared himself for the abolition of the monarchy we now know that was just one of his many faces and many lies.

George Orwell on constitutional monarchy

“It is a strange fact, but it is unquestionably true, that almost any English intellectual would feel more ashamed of standing to attention during “God Save the King” than stealing from a poor box” ― George Orwell, A Collection of Essays

In contemplating the British republican movement’s call for a referendum on the monarchy following the demise of the Queen, we inevitably delve into the realm of political discourse and the eternal query: “What verdict would George Orwell pass on this matter?”.

While Orwell’s sentiments toward the Royal Family were not entirely uniform, he did espouse the virtues of a constitutional monarchy devoid of substantive authority. In his view, such a system served as a vital check against the lurking dangers of fascism, warranting cautious consideration.

In a 1944 article for Partisan Review, he wrote:

The function of the King in promoting stability and acting as a sort of keystone in a non-democratic society is, of course, obvious. But he also has, or can have, the function of acting as an escape valve for dangerous emotions.

A French journalist said to me once that the monarchy was one of the things that have saved Britain from Fascism. What he meant was that modern people can’t get along without drums, flags and loyalty parades, and that it is better that they should tie their leader-worship on to some figure who has no real power. In a dictatorship, the power and the glory belong to the same person.

In England the real power belongs to unprepossessing men in bowler hats: the creature who rides in a gilded coach behind soldiers in steel breastplates is really a waxwork. It is at any rate possible that while this division of function exists a Hitler or a Stalin cannot come to power.

On the whole, the European countries which have most successfully avoided fascism have been constitutional monarchies. The conditions seemingly are that the royal family shall be long-established and taken for granted, shall understand its own position and shall not produce strong characters with political ambitions. These have been fulfilled in Britain, the Low Countries and Scandinavia, but not in, say, Spain or Romania.

If you point these facts out to the average left-winger he gets very angry, but only because he has not examined the nature of his own feelings toward Stalin. I do not defend the institution of Monarchy in an absolute sense, but I think that in an age like our own, it may have an inoculating effect and certainly it does far less harm than the existence of our so-called aristocracy.

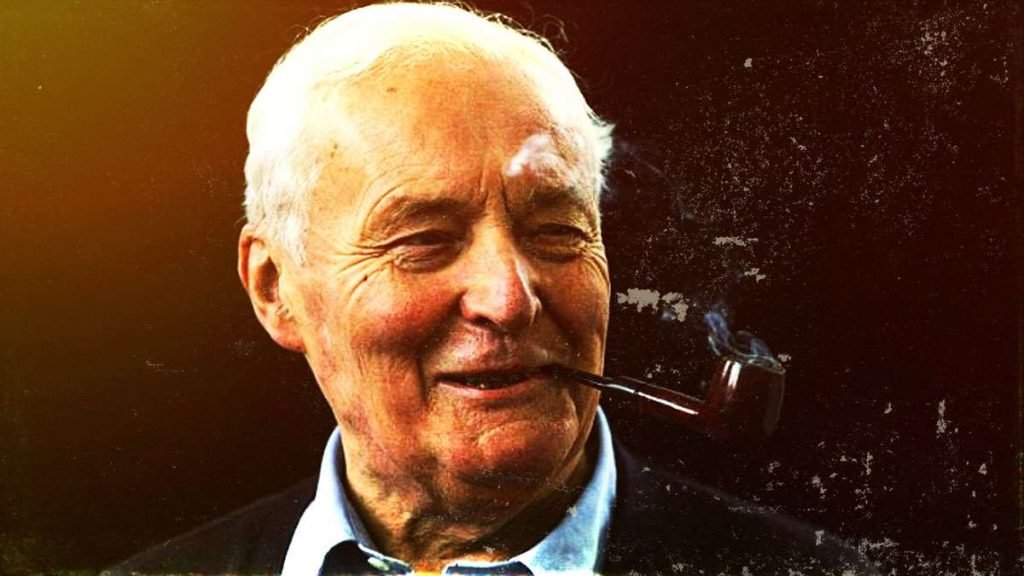

The Commonwealth of Britain Bill

In a purposely titled book ‘Common Sense‘: New Constitution for Britain, Tony Benn and Andrew Hood laid out a new constitution and goal of a republic for Britain.

The Commonwealth of Britain Bill was a bill first introduced in 1991 by Tony Benn, then a Labour Member of Parliament in the House of Commons and was seconded by the future Leader of the Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn. It proposed abolishing the British monarchy, with the United Kingdom becoming a “democratic, federal and secular Commonwealth of Britain”, or in effect a republic with a codified constitution. It was introduced by Benn a number of times until Benn’s retirement in 2001, but never achieved a second reading. Under the Bill:

- The monarchy would be abolished and the constitutional status of the Crown ended;

- The Church of England would be disestablished;

- The head of state would be a president, elected by a joint sitting of both Houses of the Commonwealth Parliament;

- The functions of the royal prerogative would be transferred to Parliament;

- The Privy Council would be abolished, and replaced by a Council of State;

- The House of Lords would be replaced by an elected House of the People, with equal representation of men and women;

- The House of Commons would similarly have equal representation of men and women;

- England, Scotland and Wales would have their own devolved National Parliaments with responsibility for devolved matters as agreed;

- County Court judges and magistrates would be elected; and

- British jurisdiction over Northern Ireland would be ended.

- The judiciary would be reformed and a National Legal Service would be created.

- The Constitution would be codified and an amendment process established.

- The voting age would be lowered from 18 to 16.

- MPs and other officials would swear oaths to the Constitution, not the Crown.

Martyn Rush articulates the bill best in his article for the Tribune: Tony Benn first moved the Commonwealth of Britain Bill. The proposal was to transform the United Kingdom into a democratic, federal, secular republic—a ‘Commonwealth’—with a constitution guaranteeing economic and social rights.

The Bill proposed that Britain would become a republic – the monarchy would be abolished, the Royal Family pensioned off, the honours system disbanded, and the crown estates nationalised. It would be truly democratic, with supremacy resting in a Parliament consisting of two democratically elected chambers.

Today, it is crucial for the Left to recover and renew this vision. At a time when Labour’s conversation about constitutional reform is fixated on narrow, incremental amendments, Bill’s anniversary is a reminder of the radical ideas discussed in our not-too-distant past. And it contains plenty of measures of enduring relevance for today’s politics.

For instance, under Benn’s bill, Britain would have become truly federal – its new Parliament would look after the defence, foreign affairs, and the Commonwealth economy, all other matters would devolve to the national Parliaments of England, Scotland and Wales; jurisdiction over Northern Ireland would be terminated.

The new Commonwealth would also be secular – the Church of England would be formally disestablished. The Head of State would be a President elected by Parliament. A written constitution codified the powers of government and safeguarded the rights of citizens. It would be the Constitution—rather than a particular family—that all public servants, MPs, and the armed forces would swear to defend.

The Commonwealth Parliament would have a House of Commons and a House of the People. The latter, replacing the House of Lords, would consist of a gender-balanced chamber elected every four years proportionally from among the nations. A President would be elected by a two-thirds vote in both Houses, to play a largely ceremonial role of up to six years, signing bills into law, enacting the will of Parliament in foreign affairs, and signing treaties.

Under the plan, each nation was to have its own Parliament. Unlike the Scottish Parliament and the Welsh Assembly, which did take shape after Benn’s bill, the national Parliaments would have control over everything except defence, foreign affairs, and the Commonwealth economy. Similarly, local councils would be liberated, freed to do anything which did not contradict Commonwealth law.

Benn clearly hoped that this would allow the rebirth of municipal socialism, and his desire to free local councils to build social justice in their communities show the scars of the 1980s battles over the Greater London Council and the rate-capping rebellions.

In its final radical proposal, the security services and foreign policy would be brought under greater democratic control. Most foreign policy decisions, such as UN votes and international treaties, would be subject to Commons vote, and it would be unconstitutional to allow the stationing of foreign forces on Commonwealth soil, prohibiting US Air Force bases and subjecting Britain’s participation in NATO, for example, to democratic review.

Under the Commonwealth constitution, all the security services would have to justify their further existence and account for their taxpayers’ money on an annual basis. The Bill renounced jurisdiction over Northern Ireland within two years, ‘allowing the Irish, North and South, to find their own solutions to the problem of their relations.’

Thirty years on, the British state remains in desperate need of democratisation. Benn’s solution to this problem was a written constitution that enshrined popular power, and instituted what the bill framed as a ‘Charter of Rights,’ which go beyond the American constitution in guaranteeing economic and social as was as political rights.

The addition of economic and social rights to its US counterpart was explored by President Roosevelt before his death in 1945. For Benn, the Charter of Rights would ‘set out perfectly legitimate aspirations by which governments can reasonably be judged.’ Freedom of speech, assembly, organisation, religion, and traditional legal rights were all enumerated, and there was the addition of a National Legal Service to provide free legal support at the point of use.

But, crucially, the following social rights would also be enshrined: the right to decent housing, leisure time, access to culture, free healthcare, lifelong education, a dignified retirement, control over reproduction, free childcare, free transportation, a healthy and sustainable environment, and a media ‘free from governmental or commercial domination’. Every citizen would have the economic rights of a living wage, trade union membership, workplace democracy and the right to a sufficient state safety net.

Related articles:

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands