Peterloo Massacre: Marching for Democracy

“Rise like Lions after slumber in unvanquishable number-Shake your chains to earth like dew Which in sleep had fallen on you Ye are many they are few.” ― Percy Bysshe Shelley, The Masque of Anarchy: Written on Occasion of the Massacre at Manchester

In the annals of history, certain events cast an indelible shadow, reminding us of the price paid for the progress we often take for granted. The pages of August 16, 1819, stand as a testament to the indomitable spirit of those who dared to demand more from their leaders, and the tragic consequences that befell them. This was the day of the infamous Peterloo Massacre, a blood-stained chapter etched into the heart of Manchester, England.

Amid the cobbled streets and the hum of industry, a groundswell of working-class voices echoed through the air, converging on St Peter’s Field like a symphony of discontent. Around 60,000 souls, spanning towns and villages that would later merge into the expanse of Greater Manchester, had risen as one to champion a cause long denied to them: the reform of parliamentary representation.

The tableau that unfurled that fateful Monday would reverberate through history, a poignant illustration of power clashing with purpose. The crowd, bearing the hopes and dreams of the working masses, stood united under a banner demanding a voice in governance. Yet, the stark reality of the era, where suffrage was an entitlement reserved for wealthy landowners, stirred within them an unquenchable thirst for change.

Their aspirations converged beneath the open sky of St Peter’s Field, a gathering that sought to channel their grievances through peaceful means. They came not with weapons but with banners, not with intent to disrupt the peace but to be heard above the din of indifference. Theirs was a call for a more inclusive democracy, a plea for representation that resonated across social classes.

However, the response they received was a brutal rebuke, a thunderous cavalry charge that would forever brand this day with a name synonymous with injustice – the Peterloo Massacre. As if time stood still, the authority’s heavy-handed response descended upon the crowd, a reminder that in the theatre of progress, the stage can be stained with the blood of the innocent.

The charge into the crowd, executed with an iron fist, crushed bodies and dreams alike. Lives were forever altered, futures extinguished in an instant. The blood-soaked earth of St Peter’s Field bore witness to the collision of aspirations and authority, the repercussions of which reverberated through generations.

The Peterloo Massacre became a rallying cry, a symbol of defiance against oppression. It galvanized the spirit of reform, intensifying the quest for political equality and social justice. Out of the tragedy emerged a renewed determination to tear down the walls of an exclusionary system, to build a bridge over the chasm of inequality.

This pivotal moment in history serves as a stark reminder that the struggle for progress is often accompanied by pain and sacrifice. The echoes of that fateful day continue to resonate in our modern world, underscoring the importance of vigilance against any erosion of hard-fought rights.

The Peterloo Massacre stands not only as a historical milestone but as an enduring call to vigilance against the infringement of civil liberties. As we navigate the complex currents of today’s sociopolitical landscape, let us remember those who stood valiantly on that field, whose blood was shed for the audacious idea that governance should be a reflection of the people, for the people, and by the people.

What was the Peterloo massacre?

The Peterloo Massacre took place at St Peter’s Field, Manchester, Lancashire, England on Monday 16 August 1819. On this day, cavalry charged into a crowd of around 60,000 people who had gathered to demand the reform of parliamentary representation.

On 16 August 1819, up to 60,000 working class people from the towns and villages of what is now Greater Manchester marched to St Peter’s Field in central Manchester to demand political representation at a time when only wealthy landowners could vote.

Their peaceful protest turned bloody when Manchester magistrates ordered a private militia paid for by rich locals to storm the crowd with sabres. An estimated 18 people died and more than 650 were injured in the chaos.

Why don’t we know exactly how many people died?

Most historians agree that 14 people were definitely killed in the massacre – 15 if you include the unborn child of Elizabeth Gaunt, killed in the womb after Gaunt was beaten by constables in custody. A further three named people are believed to have either been stabbed or trampled to death, but their fate remains unconfirmed.

Nearly 700 men, women and children received extremely serious injuries. All in the name of liberty and freedom from poverty.

The Massacre occurred during a period of immense political tension and mass protests. Fewer than 2% of the population had the vote, and hunger was rife with the disastrous corn laws making bread unaffordable.

PEACEFUL ASSEMBLY

On the morning of 16th August, the crowd began to gather, conducting themselves, according to contemporary accounts, with dignity and discipline, the majority dressed in their Sunday best.

The huge open area around what’s now St Peter’s Square, Manchester, played host to an outrage against over 60,000 peaceful pro-democracy and anti-poverty protesters; an event which became known as The Peterloo Massacre.

St Peter’s Field is no longer a field, but a built-up area of central Manchester, around St Peter’s Square. A red plaque on Peter Street marks the spot, on the side of what is now the Radisson Blu hotel.

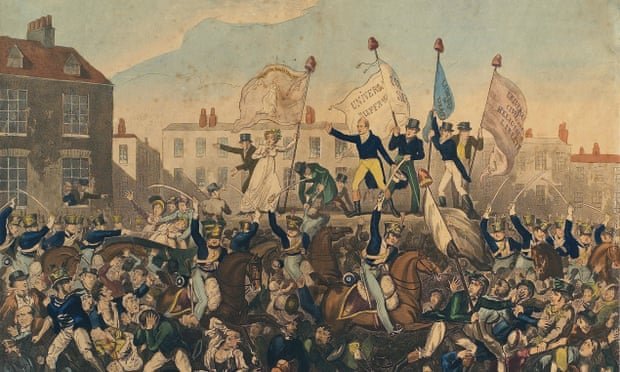

The key speaker was to be famed orator Henry Hunt, the platform consisted of a simple cart, located in the front of what’s now the Manchester Central Conference Centre, and the space was filled with banners – REFORM, UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE, EQUAL REPRESENTATION and, touchingly, LOVE.

Many of the banner poles were topped with the red cap of liberty – a powerful symbol at the time.

What did the protesters want?

They wanted political reform. At that point, only the richest landowners could vote and large swathes of the country were not adequately represented in Westminster. Manchester and Salford, which then had a population of 150,000, had no dedicated MP, yet Oxford and Cambridge Universities had their own representation in parliament dating back to 1603. So did Old Sarum, a field in Salisbury, which had no resident electorate. At the time of Peterloo, the extension of the vote to all men, let alone women, was actively opposed by many who thought it should be restricted to those of influence and means.

Why did they want to vote?

The years leading up to Peterloo had been tough for working-class people and they wanted a voice in parliament to put their needs and wants on the political agenda, inspired by the French Revolution. Machines had begun to take away jobs in the lucrative cotton industry and periodic trade slumps closed factories at short notice, putting workers out on the street. The Napoleonic wars, which ended in 1815 with the Battle of Waterloo, had taken a heavy toll on the nation’s finances, and 350,000 ex-servicemen returned home needing jobs and food. Yet those in power seemed more interested in lining their own pockets than helping the poor.

THE MASSACRE

As 600 Hussars, several hundred infantrymen; an artillery unit with two six-pounder guns, 400 men of the Cheshire cavalry and 400 special constables waited in reserve, the local Yeomanry were given the task of arresting the speakers. The Yeomanry, led by Captain Hugh Birley and Major Thomas Trafford were essentially a paramilitary force drawn from the ranks of the local mill and shop owners.

On horseback, armed with sabres and clubs, many were familiar with, and had old scores to settle with, the leading protesters. (In one instance, spotting a reporter from the radical Manchester Observer, a Yeomanry officer called out “There’s Saxton, damn him, run him through.”)

Heading for the hustings, they charged when the crowd linked arms to try and stop the arrests, and proceeded to strike down banners and people with

their swords. Rumours from the period have persistently stated the Yeomanry were drunk.

The panic was interpreted as the crowd attacking the yeomanry, and the Hussars (Led by Lieutenant Colonel Guy L’Estrange) were ordered in.

As with the Tiananmen Square Massacre, there were unlikely heroes among the military. An unnamed cavalry officer attempted to strike up the swords of the Yeomanry, crying – “For shame, gentlemen: what are you about? The people cannot get away!” But the majority joined in with the attack.

The term ‘Peterloo’, was intended to mock the soldiers who attacked unarmed civilians by echoing the term ‘Waterloo’ – the soldiers from that battle being seen by many as genuine heroes.

AFTERMATH

By 2pm the carnage was over, and the field was left full of abandoned banners and dead bodies. Journalists present at the event were arrested, others who went on to report the event were subsequently jailed. The businessman John Edward Taylor went on to help set up the Guardian newspaper as a reaction to what he’d seen.

The speakers and organizers were put on trial, at first under the charge of High treason – a charge that was reluctantly dropped by the prosecution. The Hussars and Magistrates received a message of congratulations from the Prince Regent, and were cleared of any wrong-doing by the official inquiry.

LEGACY

Historians acknowledge that Peterloo was hugely influential in ordinary people winning the right to vote, led to the rise of the Chartist Movement from which grew the Trade Unions, and also resulted in the establishment of the Manchester Guardian newspaper.

According to Nick Mansfield, director of the People’s History Museum in Manchester, “Peterloo is a critical event not only because of the number of people killed and injured, but because ultimately it changed public opinion to influence the extension of the right to vote and give us the democracy we enjoy today. It was critical to our freedoms.”

Help Us Sustain Ad-Free Journalism

Sorry, I Need To Put Out the Begging Bowl

Independent Journalism Needs You

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands