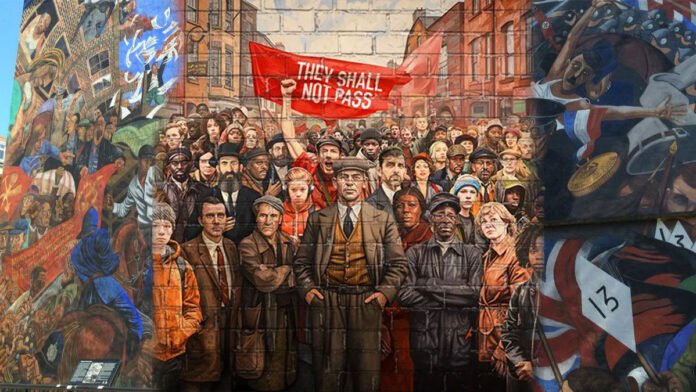

¡No pasarán!: The Day The East End Said ‘They shall not pass’

On October 4, 1936, the streets of London’s East End became a battleground for the soul of Britain. It was on this day that an unlikely coalition of Jews, communists, trade unionists, Labour Party members, Irish Catholic dockers, and local residents united in a fierce display of solidarity against the rising tide of fascism.

Their enemy? Sir Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists (BUF), who had planned to march their Blackshirts through the heart of a predominantly Jewish community. Their intention was clear: to intimidate, to divide, and to spread their poisonous ideology of hate.

But the people of the East End had other ideas. Echoing the defiant cry of the Spanish Civil War, they shouted “¡No pasarán!” – “They shall not pass!” It was more than a slogan; it was a declaration of unity in the face of bigotry, a refusal to let hatred march unchallenged through their streets.

What transpired that day would become known as the Battle of Cable Street, a pivotal moment in British history that encapsulated the nation’s resistance against the fascist wave sweeping across Europe. It was a day when ordinary people – regardless of faith, politics, or background – stood shoulder to shoulder and said: Not here. Not now. Not ever.

The threat posed by Mosley’s Blackshirts was not to be underestimated. With claimed membership of 40,000 and the backing of Lord Rothermere’s Daily Mail, the BUF represented a clear and present danger to the multicultural fabric of British society. Their march was to be a show of strength, a flexing of fascist muscle in the heart of one of London’s most diverse communities.

But in the face of this threat, the people of the East End did not cower. They did not heed the cautious advice to stay away. Instead, they came together in a remarkable display of collective courage, forming an immovable human barrier against the forces of intolerance.

The Jewish Board of Deputies advised Jews to stay away. The Jewish Chronicle warned: “Jews are urgently warned to keep away from the route of the Blackshirt march and from their meetings.

“Jews who, however innocently, become involved in any possible disorders will be actively helping anti-Semitism and Jew-baiting. Unless you want to help the Jew-baiters, keep away.”

The Battle of Cable Street stands as a testament to the power of unity in the face of division, of courage in the face of intimidation. It reminds us that when people stand together, even the most formidable forces of hatred can be turned back.

As we reflect on this historic day, let us draw inspiration from those brave souls who declared, with one voice: They shall not pass!

Eye witness account.

Before his death at the age of 93, Professor Bill Fishman, recalled “The Jews did not keep away”, Bill Fishman was 15 when he became involved in the Battle of Cable Street, he was the son of an East End tailor who became a professor of social history and one of the greatest experts on the area where he was born.

In his youth Fishman took part in “the Battle of Cable Street”, the clash between Sir Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists and Jews and others in 1936. He recalled how, as the Blackshirts advanced protected by a phalanx of mounted policemen, “We all charged towards Cable Street. At the bottom end, an overturned lorry was used as a barricade and we blocked the road – Hasidic Jews with little beards and great strapping Irish dockers all standing together. People began to throw down their mattresses to block the street and a mass onslaught on the police ensued with two officers even being taken hostage. It all came to an end about 5pm when Mosley did an about-turn. I headed to Dubowzky’s pub on Cannon Street Road, where everyone was embracing.”

Bill Fishman who was 15 on the day, was at Gardner’s Corner in Aldgate, the entrance to the East End. “There was masses of marching people. Young people, old people, all shouting ‘No Pasaran’ and ‘One two three four five – we want Mosley, dead or alive’,” he said. “It was like a massive army gathering, coming from all the side streets. Mosley was supposed to arrive at lunchtime but the hours were passing and he hadn’t come. Between 3pm and 3.30, we could see a big army of Blackshirts marching towards the confluence of Commercial Road and Whitechapel Road.

Marbles

“I pushed myself forward and because I was 6ft I could see Mosley. They were surrounded by an even greater army of police. There was to be this great advance of the police force to get the fascists through. Suddenly, the horses’ hooves were flying and the horses were falling down because the young kids were throwing marbles.”

Thousands of policemen were sandwiched between the Blackshirts and the anti-fascists. The latter were well organised and through a mole learned that the chief of police had told Mosley that his passage into the East End could be made through Cable Street.

“I heard this loudspeaker say ‘They are going to Cable Street’,” said Prof Fishman. “Suddenly a barricade was erected there and they put an old lorry in the middle of the road and old mattresses. The people up the top of the flats, mainly Irish Catholic women, were throwing rubbish on to the police. We were all side by side. I was moved to tears to see bearded Jews and Irish Catholic dockers standing up to stop Mosley. I shall never forget that as long as I live, how working-class people could get together to oppose the evil of racism.”

Max Levitas, was a message runner and had already been fined £10 in court for his anti-Mosley activities. Two years before Cable Street, the BUF had called a meeting in Hyde Park and in protest Mr Levitas whitewashed Nelson’s column, calling people to the park to drown out the fascists. Mr Levitas went on to become a Communist councillor in Stepney.

“I feel proud that I played a major part in stopping Mosley. When we heard that the march was disbanded, there was a hue and cry and the flags were going wild. They did not pass. The chief of police decided that if the march had taken place there would be death on the road – and there would have been,” he said.

His experience of the possibilities of collective action undoubtedly informed his view of the 19th-century predecessors of the Cable Street defenders, in which he moved away from the common representation of the East End poor as a passive, downtrodden underclass. In works such as East End Jewish Radicals 1875-1914 (1975) and East End 1888 (1988) he showed them as agents of change — people who, through cooperative and collective action, were capable of winning significant victories.

“It was a victory for ordinary people against racism and anti-Semitism and it should be instilled in the minds of people today. The Battle of Cable Street is a history lesson for us all. People as people must get together and stop racism and anti-Semitism so people can lead an ordinary life and develop their own ideas and religions.”

As an aside, while researching the battle of Cable Street I came across this production.

Cable Street A New Musical by Tim Gilvin and Alex KanefskyWorth. What a great idea for a production. Link

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands