AI’s Dual Nature: Opportunities and Concerns in the Era of First Contact

In the realm of artificial intelligence (AI), a cacophony of voices has arisen, echoing a Claxton-sounding and dire warning as the general public ventures closer to these emergent technological platforms.

Experts, with an air of cautiousness, implore us to “pay attention” to the profound possibilities of harm that AI may bring, further asserting that governments lack the know-how to regulate this technology safely. However, amidst the apocalyptic overtones that emanated from 350 AI experts just last week, proclaiming a potential extinction event for humanity, there also lies an ocean of vast opportunities presented by AI.

One of the pressing questions that linger is whether AI will render human beings redundant or, conversely, serve as a catalyst for job creation.

However, amidst these apocalyptic prophecies of the extinction of the human race, it is crucial to acknowledge the vast opportunities that AI holds.

The Duality of AI: Profound Possibilities and Cautious Warnings

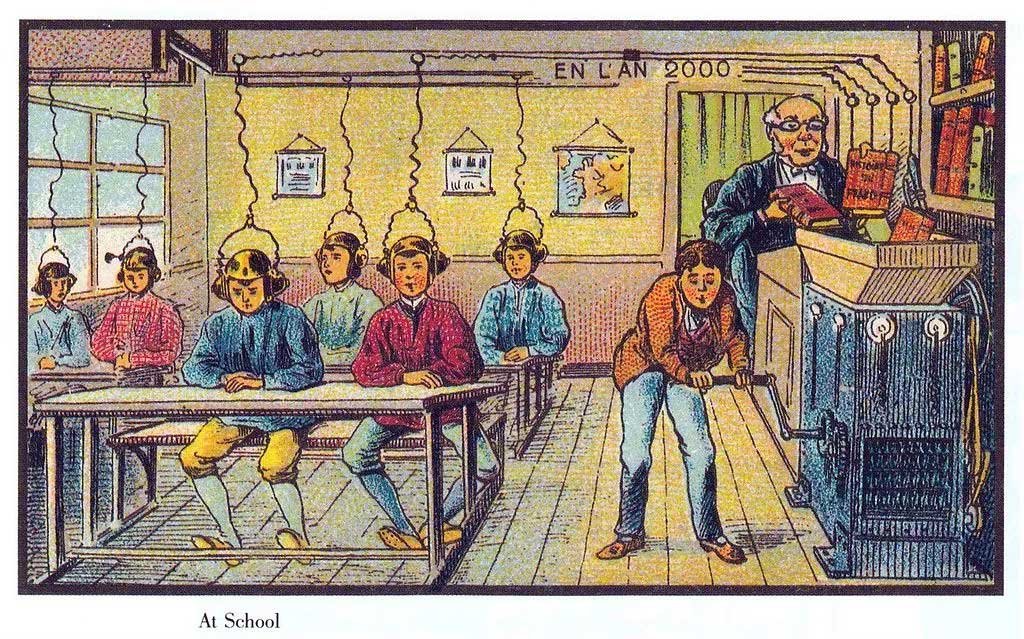

A new study conducted by Princeton, the University of Pennsylvania, and New York University sheds light on the impact of AI on different professions, revealing that telemarketers and teachers could be the most affected.

Through the use of the AI Occupational Exposure benchmark, the researchers examined how services like ChatGPT could disrupt various sectors. They concluded that post-secondary teachers in areas such as languages and literature, history, law, philosophy, religion, sociology, political science, and psychology would experience the greatest impact.

Undoubtedly, some jobs will become redundant in the wake of AI’s advancements. As Georgios Petropoulos, a researcher at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Stanford University, elucidates, routine jobs like language translators or phone operators are more susceptible to displacement by AI. Yet, amidst this concern, there is a counterbalance of hope. AI has the potential to create new employment opportunities, as Nurski highlights.

The World Economic Forum’s research in October 2020 projected that while AI may displace 85 million jobs globally by 2025, it could also generate 97 million new jobs in domains ranging from big data and machine learning to information security and digital marketing.

One certainty emerges from this debate: AI will inevitably reshape the way we work. Economists and technology analysts forecast improved productivity as a consequence of this transformation. Early evidence already indicates this shift taking place. AI systems simulate human intelligence processes, but the question that lingers is whether they could surpass human control.

Yet, amid this debate, the one certainty is that AI will undeniably reshape the way we work. Economists and technology analysts alike anticipate improved productivity as a consequence of this transformation, thereby infusing an element of progress into the equation. Already, there is mounting evidence attesting to the early stages of this phenomenon.

At its core, AI represents the simulated replication of human intelligence processes by machines. However, the question arises: Is there a risk that AI might develop to a point where it surpasses human control? To gain a deeper perspective, let us hark back to the turn of the 19th century and examine the transformative impact of technology in the United Kingdom’s textile industry.

Lessons from History: The Luddites and Technological Shifts

During that era, the textile industry stood as an unrivalled economic powerhouse in the North, employing a vast majority of the region’s workforce. Weavers, working from the comfort of their homes, utilised frames to produce stockings, while cotton spinners deftly created yarn. The croppers, entrusted with the arduous task of trimming rough surfaces off large sheets of woven wool fabric, brought a smooth finish to the final product.

This thriving workforce enjoyed substantial autonomy over their working hours and relished ample leisure time. “The year was chequered with holidays, wakes, and fairs; it was not one dull round of labour,” wrote the jubilant stocking maker William Gardiner. Some of them even revelled in working no more than three days a week, designating both weekends and Mondays as festive occasions, with the latter hailed as the notorious “St. Monday.”

Of all the labourers, the croppers held a particularly formidable position. Boasting higher wages three times that of stocking-makers, these robust and independent men, having honed their strength from the physical demands of their work, proved notoriously challenging to manage. Within the textile realm, the croppers reigned as the least malleable of all employed individuals, as astutely observed by contemporary witnesses.

However, in the early 1800s, the textile economy spiralled into a tailspin. A decade of warfare with Napoleon choked trade routes, driving up the costs of essential commodities. Simultaneously, fashion trends shifted, with men favouring “trousers” over traditional stockings, leading to a precipitous decline in demand.

Facing economic pressures, the merchant class sought means to minimise expenses, triggering a paradigm shift by embracing technology as a means of augmenting efficiency. They introduced new shearing and “gig mill” devices that enabled quicker wool cropping by a single individual. Revolutionary “wide” stocking frames emerged, enabling weavers to produce stockings six times faster by weaving large hosiery sheets and subsequently dividing them into several individual pieces. These divided stockings, known as “cut-ups,” possessed subpar quality, and quickly fell apart.

Nonetheless, they could be produced by unskilled workers who bypassed traditional apprenticeships. The merchants, driven solely by profit, disregarded the consequences. Moreover, they constructed sprawling factories, powered by coal-burning engines, housing scores of automated cotton-weaving machines.

Enraged, the workers responded vehemently. Factory labour became a gruelling ordeal, entailing excruciating 14-hour workdays that left workers physically stunted, weakened, and morally degraded, as noted by concerned physicians. Stocking weavers, in particular, railed against the proliferation of cut-ups, recognising that such shoddy goods would inevitably engender their own demise, driving away potential buyers. Poverty soared while wages plummeted.

The workers, in a bid for negotiation, expressed their openness to machinery, provided that the benefits arising from increased productivity were shared equitably. The croppers proposed levying a tax on cloth to establish a fund for those displaced by machines, while others advocated for a gradual introduction of machinery, allowing workers more time to transition to new trades.

The plight of these unemployed workers even captured the attention of acclaimed author Charlotte Brontë, who memorialised their struggles in her novel “Shirley.” She keenly observed the tremors of a “sort of moral earthquake” reverberating beneath the hills of the northern counties.

In mid-November of 1811, this metaphorical earthquake commenced its rumbling. Under the cover of night, a group of individuals, their faces blackened to conceal their identities, wielding swords, firelocks, and other offensive weapons, stormed the residence of master weaver Edward Hollingsworth in the village of Bulwell.

They dismantled six frames dedicated to cut-up production. A week later, returning with greater numbers, they reduced Hollingsworth’s home to ashes. Within weeks, similar attacks proliferated in other towns. When panicked industrialists attempted to relocate their frames, hoping to hide them from the machine-breakers, the attackers intercepted the carts, obliterating them en route.

A modus operandi emerged, characterised by machine-breakers camouflaging their identities and wielding mammoth metal sledgehammers to vanquish the machines. These hammers, fashioned by Enoch Taylor, a local blacksmith known for crafting cropping and weaving machines, epitomised poetic irony. The breakers would chant, “Enoch made them, Enoch shall break them!”—a fitting denouement.

The attackers christened themselves the Luddites, etching their name indelibly into the annals of history.

Today, perched on the precipice of the AI era, we confront a familiar quandary. Shall we assume the mantle of Luddites, crippled by fear and resistance to progress? Or shall we, akin to Prometheus, eagerly embrace this new technology and ignite a metaphorical firestorm of innovation?

However, as we tread this treacherous path, we would do well to remember the dual nature of Mary Shelley’s literary masterpiece, which bore the titles “Frankenstein” and “The Modern Prometheus.” In our current epoch, we face a similarly pivotal choice: to wholeheartedly embrace or vehemently oppose the rapid march of AI.

Just as the mythical Prometheus bestowed the gift of fire upon humanity, AI tantalises us with its vast potential. Yet, we must tread this uncharted terrain with caution and thoughtfulness, mindful of the grave consequences that can arise if we were to unwittingly unleash the modern equivalent of Frankenstein’s monstrous creation.

Is #AI a game changer? #ArthurcClarke pic.twitter.com/7HNnzl3vrE

— Labour Heartlands (@Labourheartland) June 6, 2023

The words of Arthur C. Clarke, the visionary science fiction writer and futurist, resonate in this context. He envisioned a world where AI revolutionises various domains but cautioned about the perils of advanced AI exceeding human control, as depicted in his novel “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

As we grapple with the question of AI’s impact, we must tread the fine line between fear and hope. It is imperative to have robust regulations that mitigate the risks and ensure the responsible development and deployment of AI technologies. We must also foster an environment that embraces innovation, encourages ethical practices, and prioritises the well-being of humanity. The future of AI is a complex tapestry woven with both potential and risks, and it is our collective responsibility to shape its course.

This article was proofread and corrected using ChatGPT. The image was partly made by AI. As a dyslexic person, I found the process much quicker and easier than other programs I currently use, in all the processes saved me a few hours. In my experience, I will probably continue to use AI to proofread my articles and more than definitely use AI to create the foundation of images.

Help Us Sustain Ad-Free Journalism

Sorry, I Need To Put Out the Begging Bowl

Independent Journalism Needs You

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands