“They wanted that strike. They wanted to change the political landscape of this country away from collectivism toward deregulation market forces. Reasonable people can agree or disagree with that shift; the point is in order to achieve it they needed a war!” -Extract BBC mini-series #Sherwood

Sherwood, the BBC mini-series is loosely based on the true story of two unconnected murders in the Sherwood Forest area in 2004, written by the award-winning writer of (Quiz, Brexit: An Uncivil War) James Graham who grow up in post-industrial Nottinghamshire around the miners’ strike of 1984.

The murder plot is inconsequential other than to give glue to the characters. Sherwood digs deep into the effects of the miners’ strike on the community who are still caught up in the fallout from the 1984 strike, a period that affected so many in so many different ways.

“They wanted that strike. They wanted to change the political landscape of this country away from collectivism towards deregulation market forces. Reasonable people can agree/disagree with that shift; the point is in order to achieve it they needed a war” #Sherwood pic.twitter.com/mlMBhHMmQB

— Labour Heartlands (@Labourheartland) June 23, 2022

The series is gripping and well-acted. For those of us around in the 80s growing up in pit villages, Sherwood creates the echoes of how mining communities not only battled State oppression but strived to hold together for one long year against insurmountable odds.

Some of these villages have moved on the best they could, the courage in the face of adversity is inherent within the working class, however, just like the dirty slag heaps now grassed over, underneath that green veneer the scar on the earth is still there, as are the collective memories from the people and their shattered communities.

A feeling of creeping decay in the left-behind former industrial areas that are still hunted by ghosts of the past and the injury of State betrayal carried out on the workers. Workers who for the past 200 years had been the backbone of Britain’s industrial revolution and economy, is there any wonder they felt so let down, so betrayed?

That unresolved fight and bitterness at that betrayal from both State and former comrades who broke ranks won’t go away. Miners who listened to the agents of the Oligarchy whispering sweet nothings in their ears, their ultimate reward for scabbing, to end up on the dole, treated no different to their former comrades in the NUM.

The impact of these strikes had a profound effect on everyone, not just the miners. As a miner’s son growing up in a mining village, all be it one without a breakaway scab union. I found Sherwood not only emotional but illuminating in many ways. At just over seventeen I joined the Army in 1984 as my family entered into that year-long strike.

Come August I had completed my training. My parents took the long journey from South Yorkshire to Woolwich Arsenal, a 524mile round trip to watch my passing out parade, no mean feat in the midst of a strike. Immediately after the parade, we travelled home by car. That journey opened my eyes a little to what my community have had to endure. It was then I first witnessed the State’s “Iron Heel” pressing down on the working class.

Our vehicle was stopped at every roundabout and junction from Nottingham to Yorkshire. Harassed every step of the way at what was supposed to be the police’s attempt to stop ‘flying pickets,’ in reality this was pure intimidation. At the time I was still dressed in full parade uniform! The Police didn’t show one touch of comradery for a member of the armed forces. We were subject to as I witnessed first-hand, State oppression, solely because my father was a miner and the car registration flagged up.

We were aggressively questioned, asked constantly ‘who we were, where we were going and where we had been. checkpoints were placed at roundabouts, anyone who drove the A1 in the 80s would know the roundabouts at some points were only a few hundred yards apart, and some checkpoints were clearly visible to each other. When you’re the only car to be stopped you understand you are being targeted.

These were the very same tactics learnt to me later in my military career, the tactics used on suspected IRA members in Northern Ireland when we carried out personal checks or set up a vehicle checkpoint, of course, many of these people were suspected terrorists and for security reasons you could accept this was the normality of anti-terrorist operation, however, it was always difficult to reconcile the fact those same tactics were so robustly used against my community, my family whose only crime was to withdraw their labour and carry out the right to strike.

For those reading and thinking that’s not so bad, remember the miners had committed no crime, they were just carrying out their rights to withdraw their Labour, to picket their place of work. To stop them in their everyday business was nothing more than state oppression.

Back in 1984, I was a young recruit fresh out of training, proud as punch at passing out, angry as hell at being stopped and questioned like I was a dissident by Thatcher’s boot boys, back in 1984 I was in for a shock to see how things had changed so much.

During that leave I witnessed striking miners picketing Hatfield main at the crossroads to the ‘Pit lane,’ I used the occasion to stand in solidarity with my family and community, and I remember vividly that day.

Of course, there was talk of soldiers on the picket lines wearing police uniforms. the violence shown by the met only escalated those rumours. My brother and a few others had asked me to walk the line of police officers to see if I could tell if any were serving soldiers, I couldn’t, noticeable a few wore the trademark DMS military issue boots, however, the police officers wearing them were far too old to be serving soldiers.

What was clear is throughout the pit villages there was a State-induced paranoia, and a mistrust of strangers, after all, this had turned from a fight for jobs and the right to work into something more, this was class war, and the State was using every weapon to win.

There was a strong suspicion in our communities that we had been infiltrated by government agents, undercover police placed to gather information on the Union, and pickets, to gauge the mood of the community, how much fight did they have left in them?

In the 21st century, we now know a little more through the uncovering of other operations carried out by the state we now have a name for these agents, Spycops! Back then the hardest thing was proving it. Nobody wanted a witchhunt any pursuit of infiltrators created more mistrust and further breakdown of community, the weapons of State aren’t always visible but they are destructive.

During the miners’ strike 84, there was a strong suspicion in our communities that we had been infiltrated by government agents, undercover police placed to gather information. In the 21st century we now know a little more, we now have a name for these agents #Spycops! #Sheerwood pic.twitter.com/DsxJpGXFlf

— Labour Heartlands (@Labourheartland) June 27, 2022

Those feelings of mistrust towards the State never went away. The betrayal people felt was only amplified over the years as each successive government failed in their promises to level up these post-industrial areas. Like the black patches on the grassed-over slag heaps, the truth of what lay beneath kept popping up and just as the mini-series Sherwood pointed out so clearly the truth the State had planned to take on the miners in an ideological battle came to light in what is now known as the ‘Ridley Report’.

But to what lengths the government went to is still to be resolved, and there are questions that need answering they can’t be just grassed over like the slag heaps, otherwise, these communities are never going to heal.

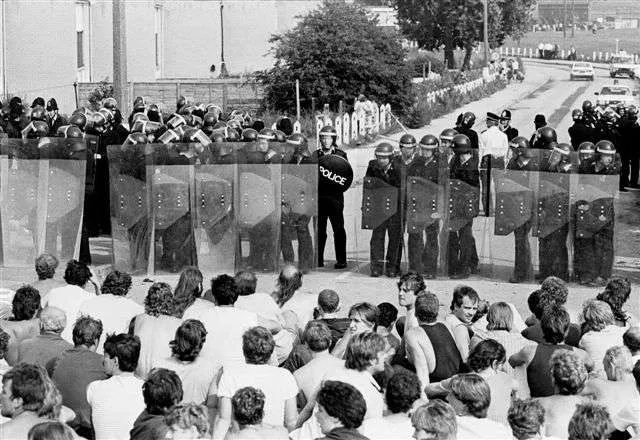

There are questions relating to Orgreave. The Orgreave Truth and Justice Campaign (OTJC) is pressing for a full and independent inquiry into what happened during the now infamous Battle of Orgreave, the images of miners being beaten and charged down by mounted police are now iconic.

The Independent Police Commission (IPCC) decided in June 2015 that, partly because of its limited terms of reference, it would not carry out a full investigation into Orgreave, although its report contained some serious criticisms of the actions and attitudes of South Yorkshire Police, implicitly suggesting that a wider inquiry was called for.

At Orgreave this involved the assaults, wrongful arrests and false prosecutions of the miners and perjury in court; but there are other questions relating to the wider communities, questions that need answering to what extent did the State go to subvert our community? Did they employ spies? Did they place undercover officers into mining communities?

Orgreave was the worst example of oppression by the state on workers in modern history this involved the assaults, wrongful arrests and false prosecutions of the miners and perjury in court by police officers; but there are other questions relating to the wider communities, questions that need answering, to what extent did the State go to subvert our community? Did they employ spies? Did they place undercover officers into mining communities?

That spring of 1984, there were 170 collieries in Britain, with 191,000 working miners. The State had planned this attack on the workers to break the power of the unions and their ability to bargain for better rights using the power of collectivism. The state wanted to shatter that strength. The length Thatcher and the Tories would go to was beyond that of an accountable democracy, for those on the receiving end it was little more than fascism

The Ridley Report. How the Tories planned to take on the miners and the working class

In 1977, Tory backbencher Nicholas Ridley presented Margaret Thatcher with a report unglamorously titled ‘Final Report of the Nationalised Industries Policy Group‘ – later to become known as the ‘Ridley Plan’.

Ridley, the son of a wealthy family whose coal and steel interests had been nationalised under the Attlee government, was implacably opposed to public ownership. And beneath its innocuous title, the Ridley Plan amounted to an astonishingly ruthless and hard-headed battle plan for privatisation – one which was to guide the Thatcherites’ assault on the nationalised industries, and whose repercussions are still with us today.

The Ridley Plan prefigures almost all of the key moments in the long neoliberal assault on public ownership, from the open war against the miners to the privatisation “by stealth” (Ridley’s own words) of the NHS. It suggests that Thatcher pick her battles, provoking confrontations in “non-vulnerable industry, where we can win” such as the railways and the civil service, while taking steps to create the conditions for eventual victory against the more powerful trade unions. It outlines a plan to prepare the ground for privatisation by introducing market measures in the running of nationalised industries (such as changes of leadership, targets for return on capital, and new incentives for managers), and fragmenting the public sector into independent units that could later be sold off.

Ridley explicitly describes this as a “long term strategy of fragmentation”, “a cautious ‘salami’ approach – one thin slice at a time, but by the end the whole lot has still gone”. In a controversial appendix entitled ‘Countering the Political Threat’, leaked to the Economist in 1978, he even anticipated the pitched battles of the miners’ strike, highlighting the need for “a large, mobile squad of police who are equipped and prepared to uphold the law” against violent picketing.

The Tories had been thrown out of office in 1974, during the big upturn in strike action which is best remembered for its miners’ strikes, with power cuts and the three day week. Ted Heath went to the polls asking the question: “who runs the country” and lost! The ‘70s were a period where wave after wave of industrial struggle forced the bourgeoisie to look to more extreme measures than ‘usual’, while at the same time the working class, the unions and the Labour Party began to move towards the left. Many workers began to draw revolutionary conclusions on the basis of their experience, while Brigadier Kitson began to plot a military coup to overthrow that well known revolutionary, Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson.

In 1974 the Tories drew up a plan as to how they might take on and defeat a major trade union in the public sector or nationalised industries as they were known at the time! Essentially it was a plan to launch a one-sided civil war against the working class. The plan was quite thorough, as became obvious when it was leaked to the Economist in 1978:

- The government should, if possible, choose who and when to fight;

- The plan grouped industries together based on an assessment of how easy they might be to beat;

- Coal stocks were to be built up at the power stations;

- Coal supplies should be arranged via non-union foreign ports

- Non-union lorry drivers should be recruited;

- Coal/oil dual fuel generators should be built at whatever cost;

- The state must “cut off the money supply to the strikers and make the union finance them”;

- It was necessary to organise and equip a squad of mobile police, ready to use riot tactics to defeat pickets.

But Ridley was no maverick, and it’s quite clear he wasn’t acting alone. The plan was agreed by the Selsdon Group of right wing Tory MPs, a group that included among its number both Norman Tebbitt and Margaret Thatcher who was elected Tory leader in 1975.

Margaret Thatcher was eventually elected Prime Minister in 1979, by which time the right wing Labour government was utterly discredited and the leadership isolated within the active layers of the labour movement. Society was polarised, the Tories began to implement an economic strategy designed to make the economy ‘leaner and fitter’. In other words, they sought to make the working class pay for the economic crisis that erupted between 1979 and1981. The Tories responded by slashing benefits to the old and the sick, cutting services and attempting to roll back the welfare state, under the banner of “self reliance”, “choice” and “the free market”.

“I warn all trade unionists – if they don’t support the miners, when it comes to your turn there will be nobody left to defend you because the police paramilitary operation would have succeeded.”

— Miners Strike (@Miners_Strike) August 6, 2021

National Union of Mineworkers president, Arthur Scargill, during the #MinersStrike pic.twitter.com/CCSZVTj6UH

The Ridley Plan was central to this programme, the straightforward reason being that the organised Labour and trade union movement represented the biggest single obstacle to their plans. 10 million workers were organised in the TUC, potentially the most powerful force in British society, and the working class was moving to the left. The Tories had to risk a confrontation with the unions.

The ruling class had no option, under conditions of capitalist crisis. Like the conditions, we face today either the bosses or the workers had to pay. In the minds of Thatcher and her cronies, there was ‘no alternative’, the workers would be the ones to lose every time.

Today we are seeing the shift once again as unions are being attacked for little more than trying to negotiate a fair wage and working conditions. All workers are feeling the pain brought about by the #CostOfLivingCrisis, it’s not the demands for wage increases that are putting prices up, it’s the greed and profiteering of the oligarchy doing that.

Lessons from the miners’ strike should be learnt, the government have plans that don’t include us getting a fair deal but more so only by standing together can we fight back.

Images courtesy of Report Digitial which has a full archive of images relating to the miners’ strike.

For more images reflecting the working class struggle then and now please go to this Report Digitial

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands