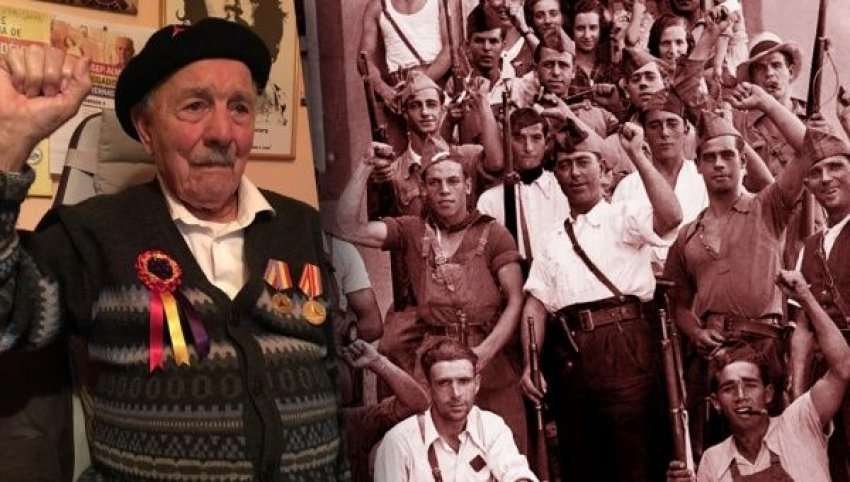

Josep Almudéver Mateu, the last-known survivor of the 35,000 foreign volunteers who joined the International Brigades to fight against fascism during the Spanish Civil War of 1936-1939, died May 23 in a hospital near his home in Pamiers, France. He was 101.

The Madrid-based Association of Friends of the International Brigades described Josep Almudéver as “the last man standing,” at the announcement of his death.

Josep Eduard Almudéver Mateu was born in the port city of Marseille, France, on July 30, 1919. His father was a builder from Spain’s Valencia region who had moved to France to seek work at the start of World War I, and his mother was from a Spanish family circus that was touring France at the time.

The family returned to Valencia when Josep was a boy, and his friends called him José. He was at school in Alcàsser, just south of the city of Valencia, when Franco and other generals, backed by Germany’s Adolf Hitler and the Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, launched a coup against the republican government in July 1936, triggering the civil war.

The Second Republic had been proclaimed in 1931, after King Alfonso XIII was deposed, and introduced a modern constitution to enshrine freedom of speech and social equality. Several governments ensued until Franco and his military rebels began an uprising in Spanish Morocco in July 1936, which led to the three-year civil war that brought about the end of the Second Republic in 1939 and the beginning of Franco’s 36-year dictatorship.

The International Brigade call for volunteers began at the onset of hostilities, known as the Brigadas Internacionales, it comprised of military units set up by the Communist International created to assist the Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Civil War.

Due to the international political climate at the time, the war had many facets and was variously viewed as class struggle, a religious struggle, a struggle between dictatorship and republican democracy, between revolution and counterrevolution, and between fascism and communism. According to Claude Bowers, U.S. ambassador to Spain during the war, it was the “dress rehearsal” for World War II.

Josep Eduard Almudéver Mateu, was not quite 17 when he lied about his age to enlist in the regular army of the elected Spanish Republican government, the war was to become a bloody conflict, a fight against tyranny and fascism with the insurrectionist “nationalist” (essentially fascist) forces of Gen. Francisco Franco pitched against Republicans loyal to the left-leaning Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic, in alliance with anarchists, of the communist and syndicalist.

Josep Almudéver was initially assigned to a battalion defending Alcàsser (his hometown) and Valencia, cities near Spain’s southeastern coast. In late 1936, he was sent to the front lines to attack a group of Franco’s forces that had taken Teruel, a key town on the road to the capital, Madrid. He was in the trenches in February 1937 when officers realised his age and sent him packing home.

The International Brigade

Having been born in France (where his Spanish parents were briefly working), he soon transferred to the International Brigades, many of whose fighters saw the battle for Spain as the spearhead of an effort to crush fascism throughout Europe.

Such was the passion aroused for the cause that intellectuals and renowned writers including George Orwell and Ernest Hemingway joined peasants, workers, Communists and anarchists. They received no support from Western governments, while the fascists who were fighting to reinstate the old order enjoyed direct assistance from Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany.

Thousands of volunteers from Britain, Ireland, United States, Italy, France, Belgium and many others who came from around the world to defend Spanish democracy.

Almost 3,000 British and Irish along with nearly another 3,000 Americans joined the International Brigades despite their relative countries neutrality.

In May 1938, by then 18 and using his French passport, Josep Almudéver enlisted in the International Brigades, which tried to make up in idealistic fervour what they often lacked in supplies.

“We went to the front without bullets,” Josep Almudéver recalled to the Spanish newspaper El Pais in 2011. “After five kilometres, a column [of fighters] from the Spanish Communist Party gave me five, then a colonel gave me five more. Ten bullets to fight a war!”

During almost six months of action, he suffered an arm injury after being hit by shells from a howitzer and was moved to the rear of the column.

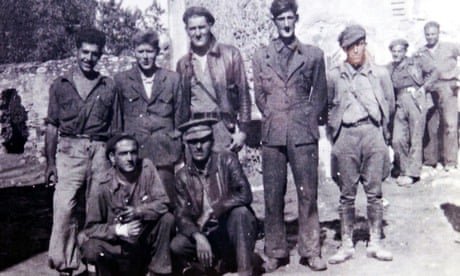

Shortly afterwards, an order from Spain’s defence minister forbade foreigners to serve in the republic’s armies, so in 1938, using his French citizenship, Almudéver was accepted by the Italian Rosselli Column in Alcàsser, alongside Canadians, Cubans, Germans, Chinese and other nationalities, under the command of the 129th International Brigade.

Within weeks, he was wounded in the arm and leg, and as Franco’s forces pushed forward, he ended up going underground in the Mediterranean town of Alicante.

The fascists entered Madrid in triumph and Josep Almudéver forever decried the policy, recognising the crusade as a chance to stem the tide of fascism and possibly avert the Second World War. He also dismissed the notion that it was a civil war, pointing out that the involvement of other countries made it a world war fought on a small stage.

By the time Franco declared victory in April 1939, the International Brigades had been disbanded and most of the foreign fighters had returned home. But others, including Josep, were rounded up and sent to concentration camps.

He was first taken to the Albatera camp near Alicante, where, he said, many were put before a firing squad or died of starvation. “I don’t know why, but they always made me watch when they shot people who had tried to escape from the camp,” Josep Almudéver told El Pais. “Never, in all my life, will I forget the screams of the people who were shot.”

There were more than 190 concentration camps, holding 170,000 prisoners in 1938 and between 367,000 and about half a million prisoners when the war ended in 1939 but of them all, the researcher Felipe Mejías has said that the camp at Albatera, on the present day site of San Isidro railway station, was the most important of them all.

It is estimated that 25,000 people died at the camp, all of which remains is a small brick shed that was close to the gatehouse and which is now used as a tool store.

Josep Almudéver also spent three years in other camps or prisons before being released in 1942. With Franco in power, and still facing reprisals, he fled into exile in Pamiers, close to the Pyrenees mountain region near the Spanish border. He worked in the construction sector while campaigning for the rest of his life against fascism.

The Association of Friends of the International Brigades said Mr. Almudéver, who eventually gave speeches about his role in the civil war, was glad he lived to see not just Spain transition to democracy after Franco’s death in 1975 but also the dictator’s body exhumed in 2019 from his elaborate mausoleum to be reburied in a municipal cemetery.

After a brief move to Morocco, the family returned to Spain to live in Alcàsser when Josep was a boy. He fondly recalled the “first euphoric week and the explosion of freedom on the streets” after the Republic was declared in 1931 when he was 11. “For the first time, secular schools were created to educate children,” he said. “The Republic was also the first government that gave equality to women. Women could now vote, be elected and be educated.”

In 2016 Josep Eduard Almudéver Mateu was presented with the Honorary Medal of Freedom by the Absent Government of the Republic in Spain.

He is survived by his brother, Vicente, 104, who fought in the regular Republican army during the battles of Jarama and Madrid, and his three sons, Ivan, Amar and Jean-Pierre, and two daughters, Ilda and Sonia. His wife, Carmen Ballester Vicens, died in 2006.

No Pasarán!

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands