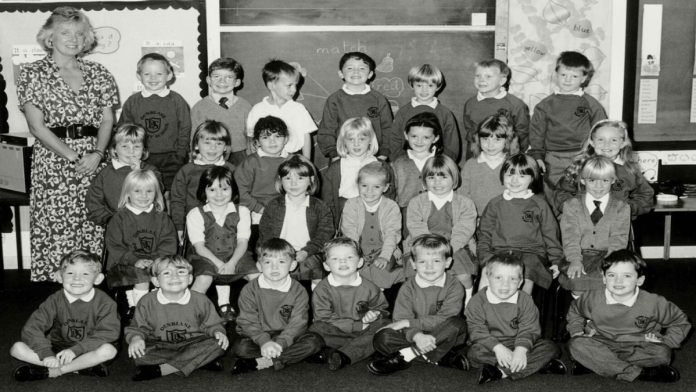

People in the Scottish town of Dunblane will mark the 25th anniversary of Britain’s worst mass shooting, which led to the introduction of some of the world’s toughest gun laws.

Sixteen schoolchildren, all of them aged just five and six, were killed with the teacher who tried to protect them when a local man opened fire on a gym class before taking his own life.

Coronavirus restrictions have shut churches across Scotland, forcing a day of private reflection.

But Colin Renwick, minister at Dunblane Cathedral, said the victims would be remembered at an online service.

“For those who lost someone in the tragedy, every day will be one of remembering in some way, and the anniversaries that will be just as poignant for them will be the birthdays of those they have lost, as they ponder what might have been,” he said.

Memories of the morning of 13 March 1996 are seared in the memory of people in Dunblane, and the rest of Britain, which stopped in horror as news of the tragedy broke.

The fact that Thomas Hamilton, 43, committed the atrocity with legally held handguns prompted a campaign for an overhaul in Britain’s gun-ownership laws.

Peter Squires, a professor of criminology and public policy at the University of Brighton and a member of the Gun Control Network founded after the shooting, said it was a turning point.

“It triggered a whole load of new thinking about what you need to do to make society safe from guns,” he added.

Within months, more than 700,000 people had signed the Snowdrop Petition set up by the families of the victims, calling for stricter gun controls.

By 1997, their high-profile campaign of speeches, media appearances and political lobbying had paid off, despite fierce resistance from gun clubs and recreational shooters.

New laws were passed prohibiting the ownership of handguns, which Mr Squires said have since been held up as a model around the world.

The government compensated handgun owners who handed in their weapons to police stations during an amnesty period.

The Gun Control Network was founded in the aftermath of Dunblane, with the Snowdrop Petition launched to rally support for a crackdown on handguns in the UK.

Within a year of the tragedy, John Major’s Conservative government introduced legislation to ban handguns over .22 calibre. In 1997 the Labour government extended this ban to cover all handguns.

The Herald newspaper reported yesterday that in 1997, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, then a newspaper columnist, called the confiscations “pointless”.

Official statistics showed guns were used in just 0.2% of all police recorded offences in England and Wales, with 33 deaths due to firearm offences. The figures for Scotland are even lower.

The only comparable mass shooting was in 2010, when 12 people were shot dead by a licensed firearm holder in Cumbria, northwest England.

‘Always remember’

Apart from a memorial to the victims of the shooting, there are few visible reminders in Dunblane of what happened.

But the pain is still palpable.

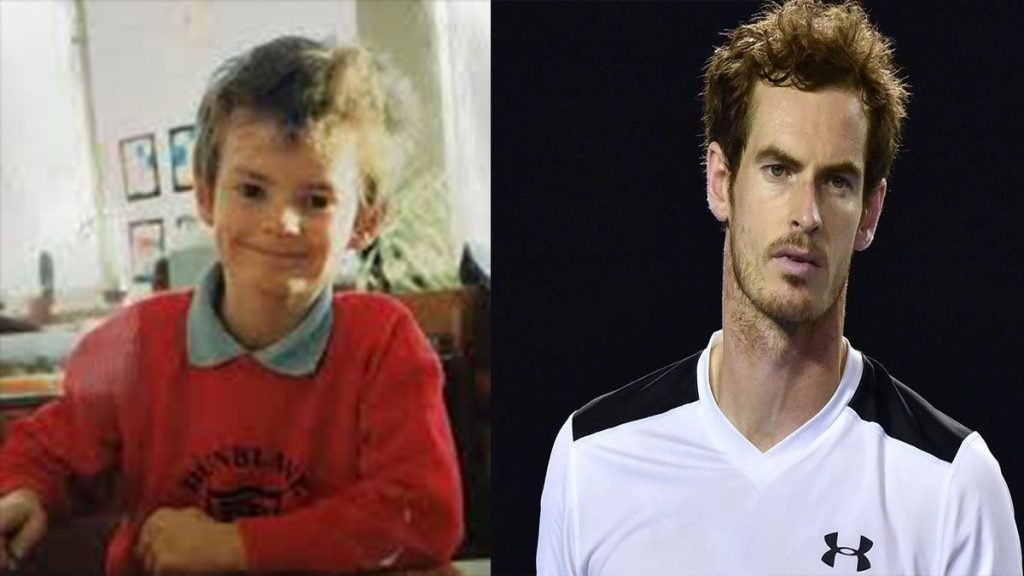

Andy Murray, the world’s former number one tennis player, was an eight-year-old pupil at Dunblane Primary School when Hamilton burst in.

He told film-maker Olivia Cappuccini: “You asked me a while ago why tennis was important to me. Obviously I had the thing that happened at Dunblane. When I was around nine.

“I am sure for all the kids there it would be difficult for different reasons. The fact we knew the guy, we went to his kids club, he had been in our car, we had driven and dropped him off at train stations and things.’

“Within 12 months of that happening, our parents got divorced. It was a difficult time that for kids.

“And then six to 12 months after that, my brother also moved away from home. He went away to train to play tennis in Cambridge.

“We obviously used to do everything together. When he moved away that was also quite hard for me.”

He opened up about his anxiety following the events.

He added: “When I was competing I would get really bad breathing problems.

“My feeling towards tennis is that it’s an escape for me in some ways. Because all of these things are stuff that I have bottled up.”

“At the time, you have no idea how tough something like that is,” he told the BBC in a June 2013 interview about his recollection of the day.

“As you start to get older you realise. The thing that is nice now, the whole town, they recovered from it so well.”

Dunblane 25th anniversary: US campaigner ‘given hope’ by UK gun laws

Jack Crozier and his sister Ellie Crozier lost their five-year-old sister Emma in the shooting and have made it their mission to honour her memory by supporting anti-gun campaigners.

Their focus is on the US, where more than 19,000 people were killed due to firearms last year, according to the Gun Violence Archive.

Dunblane campaigners supported calls for a change to US gun laws after the 2012 massacre at Sandy Hook elementary school in Connecticut, which killed 20 children and six staff.

“Eyes are going to be on Dunblane, and we don’t need the eyes on Dunblane anymore,” Jack Crozier told STV.

“We remember what happened there and we will always remember the people that we lost.

“But we need to be looking at what is going on in other countries, and America in particular.”

Jack Crozier told the BBC : “The anniversary is going to be difficult for my parents.

“We never forget the loved ones we lost. We take this as an opportunity to remember them.

“For me the most important part is to make sure that this never happens again.”

Mr Crozier said it was not “a straight change” in the UK to pass stricter firearms legislation.

He said: “It took over a year of work from my parents and other campaigners from Dunblane to make the changes we needed.

“All we can hope to offer is that onus to keep going.

“Anything they (US relatives) can bring from what we’ve done and learned, then please take that”.

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands