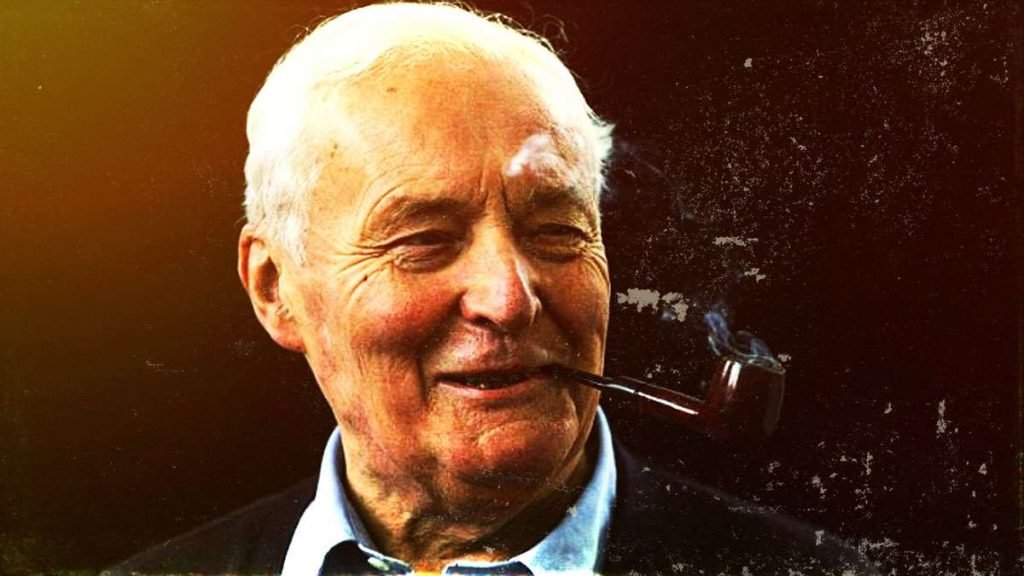

Continuing with our working-class Heroes and great orators we come to Tony Benn, although not of the working class Benn was a hero to the working class. We are spoilt for choice in showcasing his best speeches all of which could stand could be screened, however, we chose this particular speech not only for the way Benn makes us all empathise with the victims of war but also for its lost opportunity a message the world ignored, a siren warning to the Blairites, a moment in history that witnessed the shift from a working-class party to one of neoliberalism. A New Labour party that pushed headlong into war. A that we all still feel the repercussions of today. A war that has continued in a destabilised middle east for the last 23 years.

Benn stated in his speech: “Every Member of Parliament tonight who votes for the Government motion will be consciously and deliberately accepting responsibility for the deaths of innocent people if the war begins, as I fear it will.”

Many still feel Tony Blair should stand trial for taking the UK into this illegal war.

Professor of Political & Social Theory Alan Finlayson once asked the question while talking of Tony Benn stated when people recalled a Benn speech it is in a way they might remember the first time they heard a piece of music, saw an artwork or read a great poem.

This is, of course, a testament to Benn’s eloquence. But I think it’s also more than that. It’s a testament to the power of political speech and to the persistence of our desire for memorable and moving oratory. At first blush, this seems odd. We live at a time when platform oratory has long since given way to the fake stridency of celebrity columnists, the inchoate hostility of blog-commenting keyboard warriors and the crowd-sourcing of opinion in 280 characters.

Yet the memorialising of Benn’s eloquence is not only nostalgia. It is a reminder that there is a fundamental connection between speaking well and democratic life in a just society. All of us, instinctively knows this.

It is why the characteristic institution of a democracy is a debating chamber. It is why democracies put free speech at the top of their list of fundamental rights. And it is also why all tyrannies start by suppressing speech.

What is politics’ most characteristic action?

It is standing up and making known to others what you think, feel and believe. It might be at a council meeting. It might be as part of a noisy demonstration. It might be in a letter to an MP.

The political theorist Hannah Arendt thought that when we do this kind of thing we are, in a way, born anew. Through such speaking, she thought, we become more than a body labouring on the world to survive.

We become a citizen – seen and heard by others who recognise us as a free person sharing in the governing of a free society. And in seeking to persuade others to see things our way, responding to the arguments made against us, we open up the possibility that each of us might transcend our immediate selfish wants and begin to think about what might be best not only for us but for the entire community of citizens of which we are a part.

Without such speech, without places from which to do it and without people who can do it (people who can utter more than the routine cliches of ‘tough choices’, ‘hardworking families’ and ‘going forward’) there is no democracy and no politics. Benn, evidently, could do this well. Indeed, he possessed three attributes that are essential for any successful rhetorician.

The first was conviction.

Nobody sounds appealing if they are not themselves sure of their own position and of how and why it is different from others. This is not the same as being dogmatic or stubborn. It is, rather, a matter of knowing not only what you think but also why you think it. Then you are able to apply your values to the varied and challenging situations that politics throws at you.

The, second thing was knowledge.

Benn was widely read and knew a lot about political history and practice. He also travelled around and so knew a lot about the people and places of the country. Too many political people are familiar only with one kind of person – and their ignorance of the lives of the rest of us is often all too apparent.

The third is a little more specific.

Like all very successful orators Benn was skilled at the invention and use of metaphors. A lot of political argument is really about getting people to see the world or some part of it in a certain way. Metaphors are all about showing one thing in the light of another. As such they can help us think about things in new ways.

Vote on Iraq bombing – 1998 Tony Benn

17 February 1998, Westminster, United Kingdom

I finish just by saying this: war is an easy thing to talk about; there are not many people – a – of the generation that remember it. The right hon. Member for Old Bexley and Sidcup served with distinction in the last war. I never killed anyone but I wore uniform. But I was in London in the blitz in 1940, living in the Millbank tower, where I was born. Some different ideas have come in since. And every night, I went down to the shelter in Thames house. Every morning, I saw dockland burning. Five hundred people were killed in Westminster one night by a land mine. It was terrifying. Aren’t Arabs terrified? Aren’t Iraqis terrified? Don’t Arab and Iraqi women weep when their children die? Does bombing strengthen their determination? What fools we are to live in a generation for which war is a computer game for our children and just an interesting little channel for news item.

Every Member of Parliament tonight who votes for the Government motion will be consciously and deliberately accepting responsibility for the deaths of innocent people if the war begins, as I fear it will. Now that’s for their decision to take. But this is a quite unique debate. In my parliamentary experience, where we are asked to share responsibility for a decision we won’t really be taking, with consequences for people who have no part to play in the brutality of the regime which we are dealing with.

And I finish with this: on 24 October 1945—the right hon. Member for Old Bexley and Sidcup will remember—the United Nations charter was passed. And the words of that charter are etched into my mind and move me even as I think of them. “We the peoples of the United Nations determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our life-time has caused untold suffering to mankind”. That was the pledge of that generation to this generation, and it would be the greatest betrayal of all if we voted to abandon the charter, and take unilateral action and pretend that we were doing it in the name of the international community. And I shall vote against the motion for the reasons that I have given the house.

The above is the passage that matches the video. The full speech is below:

I have very little time. I want to develop my argument. There are many others who want to speak. 926 I hope that the House will listen to me. I know that my view is not the majority view in the House, although it may be outside this place.

I regret that I shall vote against the Government motion. The first victims of the bombing that I believe will be launched within a fortnight will be innocent people, many, if not most, of whom would like Saddam to be removed. The former Prime Minister, the right hon. Member for Huntingdon, talked about collateral damage. The military men are clever. They talk not about hydrogen bombs but about deterrence. They talk not about people but about collateral damage. They talk not about power stations and sewerage plants but about assets. The reality is that innocent people will be killed if the House votes tonight—as it manifestly will—to give the Government the authority for military action.

The bombing would also breach the United Nations charter. I do not want to argue on legal terms. If the hon. and learned Member for North-East Fife (Mr. Campbell) has read articles 41 and 42, he will know that the charter says that military action can only be decided on by the Security Council and conducted under the military staffs committee. That procedure has not been followed and cannot be followed because the five permanent members have to agree. Even for the Korean war, the United States had to go to the General Assembly to get authority because Russia was absent. That was held to be a breach, but at least an overwhelming majority was obtained.

Has there been any negotiation or diplomatic effort? Why has the Foreign Secretary not been in Baghdad, like the French Foreign Minister, the Turkish Foreign Minister and the Russian Foreign Minister? The time that the Government said that they wanted for negotiation has been used to prepare public opinion for war and to build up their military position in the Gulf.

Saddam will be strengthened again. Or he may be killed. I read today that the security forces—who are described as terrorists in other countries—have tried to kill Saddam. I should not be surprised if they succeeded.

This second action does not enjoy support from elsewhere. There is no support from Iraq’s neighbours. If what the Foreign Secretary says about the threat to the neighbours is true, why is Iran against, why is Jordan against, why is Saudi Arabia against, why is Turkey against? Where is that great support? There is no support from the opposition groups inside Iraq. The Kurds, the Shi’ites and the communists hate Saddam, but they do not want the bombing. The Pope is against it, along with 10 bishops, two cardinals, Boutros Boutros-Ghali and Perez de Cuellar. The Foreign Secretary clothes himself with the garment of the world community, but he does not have that support. We are talking about an Anglo-American preventive war. It has been planned and we are asked to authorise it in advance.

The House is clear about its view of history, but it does not say much about the history of the areas with which we are dealing. The borders of Kuwait and Iraq, which then became sacrosanct, were drawn by the British after the end of the Ottoman empire. We used chemical weapons against the Iraqis in the 1930s. Air Chief Marshal Harris, who later flattened Dresden, was instructed to drop chemical weapons.

When Saddam came to power, he was a hero of the west. The Americans used him against Iran because they hated Khomeini, who was then the figure to be removed. 927 They armed Saddam, used him and sent him anthrax. I am not anxious to make a party political point, because there is not much difference between the two sides on this, but, as the Scott report revealed, the previous Government allowed him to be armed. I had three hours with Saddam in 1990. I got the hostages out, which made it worth going. He felt betrayed by the United States, because the American ambassador in Baghdad had said to him, “If you go into Kuwait, we will treat it as an Arab matter.” That is part of the history that they know, even if we do not know it here.

In 1958, 40 years ago, Selwyn Lloyd, the Foreign Secretary and later the Speaker, told Foster Dulles that Britain would make Kuwait a Crown colony. Foster Dulles said, “What a very good idea.” We may not know that history, but in the middle east it is known.

The Conservatives have tabled an amendment asking about the objectives. That is an important issue. There is no UN resolution saying that Saddam must be toppled. It is not clear that the Government know what their objectives are. They will probably be told from Washington. Do they imagine that if we bomb Saddam for two weeks, he will say, “Oh, by the way, do come in and inspect”? The plan is misconceived.

Some hon. Members—even Opposition Members—have pointed out the double standard. I am not trying to equate Israel with Iraq, but on 8 June 1981, Israel bombed a nuclear reactor near Baghdad. What action did either party take on that? Israel is in breach of UN resolutions and has instruments of mass destruction. Mordecai Vanunu would not boast about Israeli freedom. Turkey breached UN resolutions by going into northern Cyprus. It has also recently invaded northern Iraq and has instruments of mass destruction. Lawyers should know better than anyone else that it does not matter whether we are dealing with a criminal thug or an ordinary lawbreaker—if the law is to apply, it must apply to all. Governments of both major parties have failed in that.

Prediction is difficult and dangerous, but I fear that the situation could end in a tragedy for the American and British Governments. Suez and Vietnam are not far from the minds of anyone with a sense of history. I recall what happened to Sir Anthony Eden. I heard him announce the ceasefire and saw him go on holiday to Goldeneye in Jamaica. He came back to be replaced. I am not saying that that will happen in this case, but does anyone think that the House is in a position to piggy-back on American power in the middle east? What happens if Iraq breaks up? If the Kurds are free, they will demand Kurdistan and destabilise Turkey. Anything could happen. We are sitting here as if we still had an empire—only, fortunately, we have a bigger brother with more weapons than us.

The British Government have everything at their disposal. They are permanent members of the Security Council and have the European Union presidency for six months. Where is that leadership in Europe which we were promised? It just disappeared. We are also, of course, members of the Commonwealth, in which there are great anxieties. We have thrown away our influence, which could have been used for moderation.

The amendment that I and others have tabled argues that the United Nations Security Council should decide the nature of what Kofi Annan brings back from Baghdad and whether force is to be used. Inspections and sanctions go side by side. As I said, sanctions are brutal for innocent 928 people. Then there is the real question: when will the world come to terms with the fact that chemical weapons are available to anybody? If there is an answer to that, it must involve the most meticulous observation of international law, which I feel we are abandoning.

War is easy to talk about; there are not many people left of the generation which remembers it. The right hon. Member for Old Bexley and Sidcup served with distinction in the last war. I never killed anyone but I wore uniform. I was in London during the blitz in 1940, living where the Millbank tower now stands, where I was born. Some different ideas have come in there since. Every night, I went to the shelter in Thames house. Every morning, I saw docklands burning. Five hundred people were killed in Westminster one night by a land mine. It was terrifying. Are not Arabs and Iraqis terrified? Do not Arab and Iraqi women weep when their children die? Does not bombing strengthen their determination? What fools we are to live as if war is a computer game for our children or just an interesting little Channel 4 news item.

Every Member of Parliament who votes for the Government motion will be consciously and deliberately accepting responsibility for the deaths of innocent people if the war begins, as I fear it will. That decision is for every hon. Member to take. In my parliamentary experience, this a unique debate. We are being asked to share responsibility for a decision that we will not really be taking but which will have consequences for people who have no part to play in the brutality of the regime with which we are dealing.

On 24 October 1945—the right hon. Member for Old Bexley and Sidcup will remember—the United Nations charter was passed. The words of that charter are etched on my mind and move me even as I think of them. It says: We the peoples of the United Nations determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our life-time has brought untold sorrow to mankind”. That was that generation’s pledge to this generation, and it would be the greatest betrayal of all if we voted to abandon the charter, take unilateral action and pretend that we were doing so in the name of the international community. I shall vote against the motion for the reasons that I have given.Source: https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard…

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands