From Jarrow to Botany Bay: The Tragic Tale of the Banished Miners

In the annals of trade union history, the names of the Tolpuddle Martyrs stand as a symbol of workers’ struggle against exploitation. Their tale of deportation to Australia for daring to fight for workers’ rights and protect their income is etched in our collective memory.

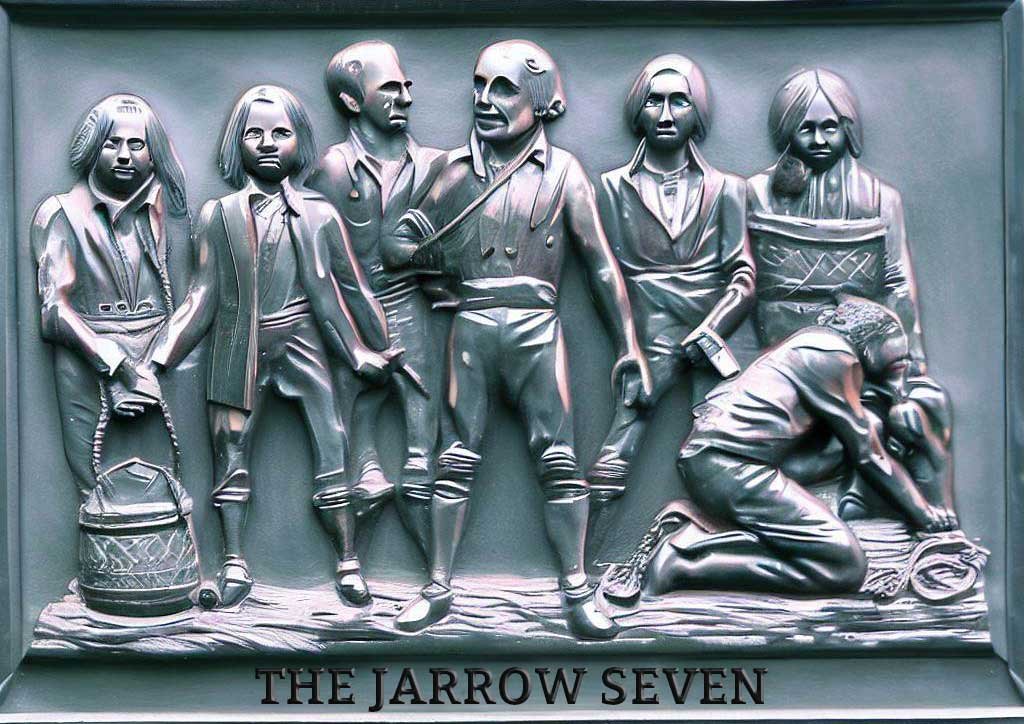

However, some tales remain untold, obscured by time and overshadowed by more well-known events. Such is the case with the story of the Seven Men of Jarrow an event that took place in 1832 – two years before Tolpuddle. Alongside their narrative, we unravel the haunting tale of William Jobling, the last man to be hanged and gibbeted in England, whose guilt still lingers in uncertainty.

Jarrow is a town that etched its name into history with the iconic Jarrow March of 1936. It owes much of its recognition to the indomitable spirit of its people and nothing exemplifies that struggle than the fight against the oppressive mining bosses and the tale of the Jarrow Seven.

A tale that gained prominence largely due to the efforts of Jarrow MP Ellen Wilkinson a national hero whose face was a prominent feature on the front page of national newspapers at every stage of the Jarrow march as she led her constituents to London.

It was her impassioned crusade that brought Jarrow’s story to the forefront of public consciousness after writing a book. Interestingly, Jarrow’s historical tale remained relatively unknown even within the North East until the publication of Wilkinson’s 1939 book, “The Town That Was Murdered.” Through her words, she shed light on the plight of her hometown, unveiling a narrative of resilience and resistance against unjust forces.

While the Tolpuddle Martyrs‘ crime was objecting to a 40% wage cut, the Jarrow miners were accused of fermenting union unrest. It was that unrest that witnessed Thomas Armstrong, John Barker, Isaac Ecclestone, David Johnson, John Smith, Bartholomew Stephenson, and John Stewart being found guilty and convicted of conspiracy and sentenced to death. However, instead of meeting the gallows, they were banished to the faraway penal colony of Botany Bay, never to return.

Their crime? Swearing a secret oath to a “friendly society” to protect their income during a time of falling wages and employer exploitation. Yet, their story remained buried in history until a recent study shed light on their plight.

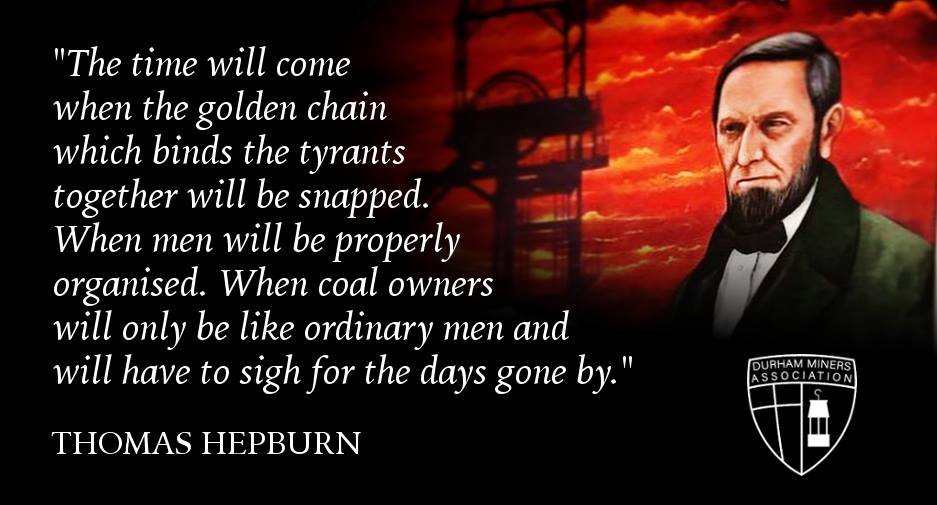

Tommy Hepburn and the United Colliers: The Fight for Workers’ Rights

The industrial landscape of 19th-century England was a battleground for workers’ rights, marred by exploitative practices and abysmal living conditions. In the face of mounting grievances, miners in Durham and Northumberland sought solace in forming unions to protect their livelihoods. One such figure was Tommy Hepburn, who spearheaded the United Colliers of Northumberland and Durham Association in 1824, later known as Hepburn’s Union.

The struggles of the miners were met with resistance from the wealthy mine owners, who vehemently opposed any demands for workers’ rights. The fight for fair wages and improved working conditions escalated into strikes and confrontations, triggering a cycle of violence between the miners, strikebreakers, and law enforcement.

In 1831, the union led its first successful strike, winning a reduction in the working hours from 18 hours to 12 hours a day – for children under the age of 12.

Following this, the colliery owners organised to destroy the union and Hepburn and other leaders were blacklisted.

Thomas Hepburn was born in Pelton in 1795. When his father was killed in a pit accident, he began work at Urpeth Colliery to support his family – at the age of eight.

He went on to work at Lamb’s Colliery in Fatfield, Jarrow Colliery, and then in 1822 at Heaton Colliery. The same year, he became a Primitive Methodist and a lay preacher.

In 1830, under the leadership of Tommy Hepburn, the Northern Union of Pitmen was established. Their primary objective was to secure better working conditions, including a reduction in the arduous working hours for children from 16 to 12 hours per day. In April 1831, the union took a stand by refusing to sign their annual bonds, which legally bound them to a specific pit for a year and a day.

The ensuing dispute was marked by bitterness, but the union managed to secure some concessions. However, the battle was far from over. In April 1832, the union once again went on strike and refused to sign the bonds.

The Jarrow Seven: Victims of Union Unrest and Unjust Sentencing

Amidst this tumultuous period, the spotlight shines on the forgotten martyrs of Jarrow, a group of seven miners whose lives took a tragic turn. Thomas Armstrong, John Barker, Isaac Ecclestone, David Johnson, John Smith, Bartholomew Stephenson, and John Stewart found themselves accused of fomenting union unrest. Charged with conspiracy, they faced a death sentence but were ultimately sentenced to deportation to the penal colony of Botany Bay.

This dark episode in history mirrors the more famous tale of the Tolpuddle Martyrs, who protested against a wage cut and suffered a similar fate. However, the story of the Seven Men of Jarrow has long languished in obscurity, known only to a few until recent years when dedicated researchers began shedding light on their plight.

The injustice suffered by these men becomes even more evident when examining the lack of evidence against them. While the convict records mention Isaac Ecclestone’s crime as house-breaking, the details for the other six men remain undisclosed. Their union activities and the accusation of calling illegal meetings were enough to cast them into the shadows of injustice.

The research revealed their names on a passenger register of the Isabella, the ship that sailed to New South Wales, Australia, in 1831. While Ecclestone’s crime was recorded as house-breaking, the convict records failed to detail any offence for the others. It appears that their union activities and their role in organizing illegal meetings to halt work at the mines were the main factors leading to their unjust deportation.

The true extent of the injustice suffered by these men becomes even more apparent when examining the glaring lack of evidence against them. While the convict records mention Isaac Ecclestone’s crime as house-breaking, the details regarding the alleged offences of the other six men remain shrouded in secrecy.

It is clear that their involvement in union activities and their role in organising meetings deemed illegal by the authorities were the primary factors that condemned them to an unjust fate.

Meticulous research has unveiled their names on the passenger register of the Isabella, the vessel that transported them to New South Wales, Australia, in 1831. Astonishingly, while Ecclestone’s crime is officially recorded as house-breaking, the convict records are conspicuously silent about any offences committed by the other men.

It becomes increasingly apparent that their persecution was driven by their involvement in unions and their efforts to halt work at the mines through unauthorised gatherings.

William Jobling, ‘the eighth Martyr’

The Jarrow miners were not the sole victims of the era’s brutal repression. In the coalfields of Durham and Northumberland, mine owners, including powerful aristocrats like the Marquess of Londonderry, vehemently opposed workers’ demands for fair treatment and better working conditions.

Their response to such demands was marked by violence, as they resorted to evicting families, dispersing pickets, and even exchanging gunfire with the miners.

The escalation of violence in the aftermath of the verdict was particularly chilling. Strikebreakers faced brutal attacks, a miner lost his life to a gunshot, families were callously evicted from their homes, and strike meetings were ruthlessly targeted by armed police.

Amidst this period of turmoil, William Jobling, a striking miner, found himself tragically entangled in a sequence of events that would see the ruin his life.

Jobling, alongside his companion Ralph Armstrong, was arrested in connection with the killing of Nicholas Fairles, a magistrate. While Armstrong was the one responsible for the fatal blow, it was Jobling who bore the weight of the murder charge.

William Jobling and Ralph Armstrong, two striking pitmen from Jarrow, launched a violent attack on Nicholas Fairles, a magistrate from South Shields. Tragically, Fairles succumbed to his injuries ten days later.

Prior to his death, Fairles identified Armstrong as the perpetrator of the attack, with Jobling serving as an accomplice. Jobling was swiftly arrested. Armstrong going on the run, evading capture and disappearing without a trace. In stark contrast, Jobling faced a swift trial and was ultimately sentenced to hang on August 3, 1832, in Durham.

The jury, astonishingly swift in reaching a verdict, deliberated for a mere 15 minutes. Jobling, the second-to-last man in Britain to be subjected to the gruesome practice of gibbeting, was executed. Gibbeting involved displaying the rotting corpse of the condemned individual in a cage as a macabre spectacle, intended to serve as a deterrent for potential wrongdoers.

The Last Gibbeting: William Jobling’s Tragic Fate

His lifeless body was covered in pitch and placed inside a metal cage, which was then transported to Jarrow Slake, where it was suspended on a towering seventeen-foot-high gibbet placed in close proximity to his family’s residence in Jarrow—a chilling reminder of the consequences of dissent.

During Jobling’s trial, Judge Parke referred to the unions as “the illegal proceedings which have disgraced the county,” cautioning others to learn from Jobling’s fate. Jobling’s body remained hanging at Jarrow Slake for three weeks until the guards were removed, providing an opportunity for his friends to risk transportation and clandestinely retrieve his remains. On the other hand, Ralph Armstrong managed to evade capture and was never apprehended.

In many ways, Jobling can be regarded as an eighth martyr, his fate tragically intertwined with that of the Seven Men of Jarrow.

By August 1832, the Union had been defeated, and Tommy Hepburn, their leader, faced severe repercussions. He was barred from working in the pits and forced to resort to selling tea door-to-door for a living. Eventually, he was permitted to return to work, on the condition that he severed all ties with the union.

In November 1830, Lord Grey formed a coalition government with the aim of quelling popular unrest, as the nation was gripped by a pervasive sense of unease.

This period of upheaval eventually culminated in the passing of the 1832 Reform Act. It is within the context of this turbulent era that the “Jobling story” should be understood, as it reflects the state of the nation in the early 1830s, described as a time when “England and Ireland were in a very disturbed and excited condition” (Earl Cowper, Preface to Lord Melbourne’s Papers, 1889).

Despite the Union’s efforts, the annual bonds they fought to abolish remained in effect until 1872. Ralph Armstrong managed to evade capture indefinitely, while Isabella Jobling, William’s widow, passed away in Harton Workhouse (now South Shields General Hospital) in 1892 at the age of 91, her memory no longer retaining any recollection of her husband.

Tommy Hepburn, on the other hand, became involved in the Chartist movement in the 1840s and found his final resting place in St Mary’s Churchyard in Heworth, Gateshead. The miners’ union continues to tend to his grave, and an annual event is held at St Mary’s in October to commemorate Hepburn’s life and contributions.

Rebel Town Festival

Ellen Wilkinson’s own background paints a portrait of determination and dedication to the cause of the working class and is more than worthy of a passing sentence. Born into a humble yet ambitious family in Manchester, she embraced socialism from an early age. Her activism extended beyond the Jarrow marches, encompassing various fronts of the battle for social justice.

Wilkinson worked tirelessly for women’s suffrage and served as a trade union officer. Drawing inspiration from the Russian Revolution of 1917, she joined the British Communist Party and ardently advocated for revolutionary socialism, all while navigating the channels of political power through the Labour Party. In 1924, she was elected as the Labour MP for Middlesbrough East, staunchly supporting the historic 1926 General Strike. Her relentlessness ensure that the tales of our working-class struggle were passed on.

In rekindling the memory of Jarrow’s struggle, we also owe a debt of gratitude to David Douglass. As a local historian and secretary of the Follonsby Wardley Miners Lodge Banner Community Heritage Group, he has played an integral role in resurrecting this poignant tale from the annals of history. Douglass’s efforts, alongside the Jarrow Festival, have breathed new life into a sombre chapter, ensuring that the sacrifices and hardships endured by the people of Jarrow are never forgotten.

Today, the Rebel Town Festival held in Jarrow stands as a testament to the enduring memory of the Seven Men and William Jobling. It serves as a poignant reminder of the injustices they endured and the profound struggles faced by the working class in their pursuit of better conditions. Their stories continue to shed light on the resilience of ordinary people against oppressive forces and the transformative power of collective action.

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands