The Chartist movement: A fight for the right to vote

The Chartist movement was the first mass movement driven by the working classes. It grew following the failure of the 1832 Reform Act to extend the vote beyond those owning property.

In an age of ascendant industry and concentrated wealth, the great mass of British workers remained voteless and voiceless – condemned to silence by a political system that prized property over people. But in 1838, a defiant cry for political rights would reverberate from the factories and mills, the downtrodden neighbourhoods where the industrial underclass survived in squalor. That year, the London Working Men’s Association drafted The People’s Charter, a petition heard round the nation that augured a gathering storm of labour unrest.

The Charter’s demands were basic, even modest – but for the ruling establishment, they bordered on revolution: universal male suffrage, yearly parliamentary elections, equal representation, and payment of members so even commoners might hold office. Unable to whip and neglect their workforce into compliance, the elite now faced a systematic agenda to check their stranglehold on power.

When Parliament first spurned the Chartist petition’s 1.25 million signatures in 1839, state retaliation was swift and severe. But the spark of resistance still smouldered – over the coming years, it would ignite in violent eruptions across the land. The uprising of the working classes had dawned, its unlikely vanguard united by The Charter’s vision of an inclusive democracy. With another rejection in 1842, the brethren were at the palace gates shaking the firmament itself with their three million voices strong.

The road was long, the costs crushingly steep – but the People’s Charter marked a revolutionary milestone toward empowerment of the labouring masses. Its principles, later enshrined into law, became the foundation for democratic reforms ushering in an age of greater – though still far from perfect – pluralism and accountability. But it took ordinary citizens marshalling their collective power to force this progress. The elites had to be pushed.

When we reflect upon the long arc of expanding enfranchisement, we recall the Chartists who forced the issue through sheer numerical strength allied to moral conviction. The establishment could not so easily dismiss the just demands of millions who knew their lives mattered no less than aristocrats ensconced in privilege. On the legacy of those humble crusaders for inclusion rests much of popular sovereignty today.

Chartists’ petition

In 1838 a People’s Charter was drawn up for the London Working Men’s Association (LWMA) by William Lovett and Francis Place, two self-educated radicals, in consultation with other members of LWMA. The Charter had six demands:

- All men to have the vote (universal manhood suffrage)

- Voting should take place by secret ballot

- Parliamentary elections every year, not once every five years

- Constituencies should be of equal size

- Members of Parliament should be paid

- The property qualification for becoming a Member of Parliament should be abolished

Unrest…

In June 1839, the Chartists’ petition was presented to the House of Commons with over 1.25 million signatures. It was rejected by Parliament. This provoked unrest which was swiftly crushed by the authorities.

A second petition was presented in May 1842, signed by over three million people but again it was rejected and further unrest and arrests followed.

Several outbreaks of violence ensued, leading to arrests and trials. One of the leaders of the movement, John Frost, on trial for treason, claimed in his defence that he had toured his territory of industrial Wales urging people not to break the law, although he was himself guilty of using language that some might interpret as a call to arms. Dr William Price of Llantrisant—more of a maverick than a mainstream Chartist—described Frost as putting “a sword in my hand and a rope around my neck”. Hardly surprisingly, there are no surviving letters outlining plans for insurrection, but physical force Chartists had undoubtedly started organising. By early autumn men were being drilled and armed in south Wales, and also in the West Riding. Secret cells were set up, covert meetings were held in the Chartist Caves at Llangynidr and weapons were manufactured as the Chartists armed themselves. Behind closed doors and in pub back rooms, plans were drawn up for a mass protest.[citation needed]

On the night of 3–4 November 1839 Frost led several thousand marchers through South Wales to the Westgate Hotel, Newport, Monmouthshire, where there was a confrontation. It seems that Frost and other local leaders were expecting to seize the town and trigger a national uprising. The result of the Newport Rising was a disaster for Chartism. The hotel was occupied by armed soldiers. A brief, violent, and bloody battle ensued. Shots were fired by both sides, although most contemporaries agree that the soldiers holding the building had vastly superior firepower. The Chartists were forced to retreat in disarray: more than twenty were killed, at least another fifty wounded.

Testimonies exist from contemporaries, such as the Yorkshire Chartist Ben Wilson, that Newport was to have been the signal for a national uprising. Despite this significant setback the movement remained remarkably buoyant and remained so until late 1842. Whilst the majority of Chartists, under the leadership of Feargus O’Connor, concentrated on petitioning for Frost, Williams and William Jones to be pardoned, significant minorities in Sheffield and Bradford planned their risings in response. Samuel Holberry led an abortive rising in Sheffield on 12 January, and on 26 January Robert Peddie attempted similar action in Bradford. In both Sheffield and Bradford spies had kept magistrates aware of the conspirators’ plans, and these attempted risings were easily quashed. Frost and two other Newport leaders, Jones and Williams, were transported. Holberry and Peddie received long prison sentences with hard labour; Holberry died in prison and became a Chartist martyr.

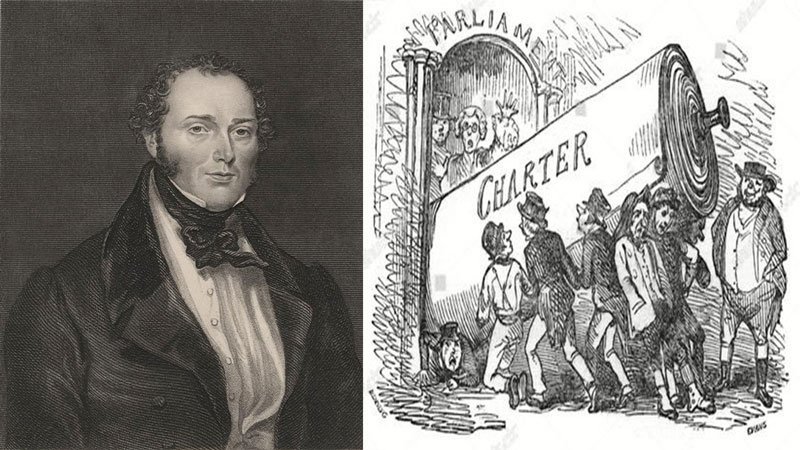

Feargus O’Connor

In April 1848 a third and final petition was presented. A mass meeting on Kennington Common in South London was organised by the Chartist movement leaders, the most influential being Feargus O’Connor, editor of ‘The Northern Star’, a weekly newspaper that promoted the Chartist cause.

O’Connor was known to have connections with radical groups which advocated reform by any means, including violence. The authorities feared disruption and military forces were on standby to deal with any unrest. The third petition was also rejected but the anticipated unrest did not happen.

Despite the Chartist leaders’ attempts to keep the movement alive, within a few years it was no longer a driving force for reform.

Chartists’ legacy

However, the Chartists’ legacy was strong. By the 1850s Members of Parliament accepted that further reform was inevitable. Further Reform Acts were passed in 1867 and 1884.

By 1918, five of the Chartists’ six demands had been achieved – only the stipulation that parliamentary elections be held every year was unfulfilled.

This document, written in 1838 mainly by William Lovett of the London Working Men’s Association, stated the ideological basis of the Chartist movement. The Charter was launched in Glasgow in May 1838, at a meeting attended by an estimated 150,000 people. Presented as a popular-style Magna Carta, it rapidly gained support across the country and its supporters became known as the Chartists. A petition, populated at Chartist meetings across Britain, was brought to London in May 1839, for Thomas Attwood to present to Parliament. It boasted 1,280,958 signatures, yet Parliament voted not to consider it. However, the Chartists continued to campaign for the six points of the Charter for many years to come, and produced two more petitions to Parliament.

The People’s Charter detailed the six key points that the Chartists believed were necessary to reform the electoral system and thus alleviate the suffering of the working classes – these were:

Universal suffrage (the right to vote)

When the Charter was written in 1838, only 18 per cent of the adult-male population of Britain could vote (before 1832 just 10 per cent could vote). The Charter proposed that the vote be extended to all adult males over the age of 21, apart from those convicted of a felony or declared insane.

No property qualification

When this document was written, potential members of Parliament needed to own property of a particular value. This prevented the vast majority of the population from standing for election. By removing the requirement of a property qualification, candidates for elections would no longer have to be selected from the upper classes.

Annual parliaments

A government could retain power as long as there was a majority of support. This made it very difficult to replace of a bad or unpopular government.

Equal representation

The 1832 Reform Act had abolished the worst excesses of ‘pocket boroughs’. A pocket borough was a parliamentary constituency owned by a single patron who controlled voting rights and could nominate the two members who were to represent the borough in Parliament. In some of these constituencies as few as six people could elect two members of Parliament. There were still great differences between constituencies, particularly in the industrial north where there were relatively few MPs compared to rural areas.

The Chartists proposed the division of the United Kingdom into 300 electoral districts, each containing an equal number of inhabitants, with no more than one representative from each district to sit in Parliament.

Payment of members

MPs were not paid for the job they did. As the vast majority of people required income from their jobs to be able to live, this meant that only people with considerable personal wealth could afford to become MPs. The Charter proposed that MPs were paid an annual salary of £500.

Vote by secret ballot

Voting at the time was done in public using a ‘show of hands’ at the ‘hustings’ (a temporary, public platform from which candidates for parliament were nominated). Landlords or employers could therefore see how their tenants or employees were voting and could intimidate them and influence their decisions. Voting was not made secret until 1871.

Paul Knaggs

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands