Tributes to the legendary and towering figure of Jack Charlton have poured in from all quarters of the footballing world in the past two weeks. However, the majority of eulogies being offered up by pundits and erstwhile colleagues alike in the mainstream media, albeit sincere, have omitted some of the defining features of Charlton’s character and heartfelt beliefs. Although his duties as both a player and manager were always his first priority, Jack Charlton proved on numerous occasions throughout his life that he refused to sever ties with the communities of which he was a product and that, to his very core, he was a staunch champion of working-class struggle.

Charlton was one of the foremost, and last remaining, symbols of a footballing era that was not completely detached from, and alienating to, the communities that, fundamentally, football clubs exist to serve and bring joy to, as an agent of relief to the masses from the interminable slog of their own less glamorous working lives. Jack Charlton, as the son of a miner and as someone who had direct experience in his youth of the trials faced by others of a similar background, had an intuitive grasp of the special reprieve football could provide for those left behind who weren’t so fortunate as to clamber from the black, sooty recesses of the coal pits to a brighter day like Jack had.

In fact, such was his deep loyalty to the mining communities to which he owed his origins, that Jack actually marched in solidarity at the annual Durham Miners Gala in 1980, demonstrating that his fleeting spell as a teenage miner before joining Leeds United had never left him in spirit and that the fraternal ethos of that gruelling labour stayed powerfully embedded in his consciousness. If this anecdote fails to inspire, ask yourself if you can imagine a world-cup winner participating in a similar democratic political exercise today. What kind of snide derision from the liberal commentariat would engulf an ex-England international taking time out from his Nike or Adidas sponsorship promotions to stand with marginalised and deprived regions today? Ask these questions and it is crystal clear just how brave and, no doubt, professionally costly such a stand was then and always will be.

Outstretching a hand of solidarity at the Durham Miners Gala was not an isolated incident in Jack’s life. His unyielding allegiance to the miners led him to actively assist those workers in their hour of need by personally loaning striking miners two cars so that they could take part in flying pickets and allowing others to collect money for their strike funds outside St. James’ Park during his time as Newcastle United manager. It’s hardly tendentious to argue that these courageous, unorthodox acts of kindness and charity towards a social group so vilified at the time probably had something to do with his being overlooked for the England managerial position itself.

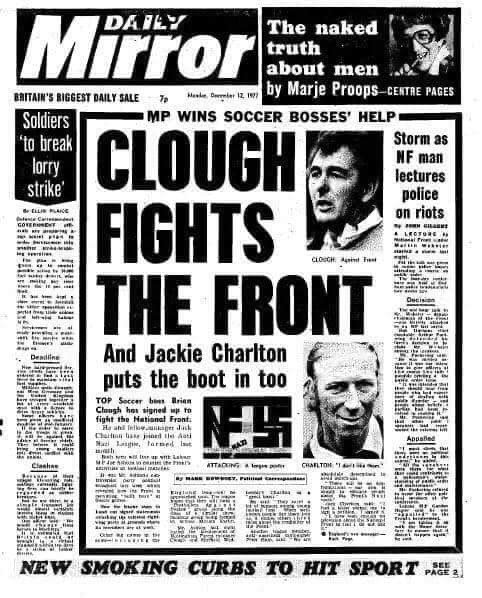

Jack’s iconoclasm did not go unnoticed by those who knew him. Remarking on his rebellious attitude, journalist and author Colin Young – who penned an authorised biography of Charlton’s life and career – said “He is anti-establishment, Jack. He is very left-wing.” It is practically inconceivable for such a characterisation to be made of a present-day manager, what with the current emphasis on wealth, status, and toeing the line on behalf of a club’s oligarchic ownership. Needless to say, this political attitude held by Jack was one of the main reasons for his being attracted to the cause of anti-Fascism at a time when the toxic influence of the National Front was deviously busying itself with the poisoning of race relations in Britain. His utter rejection of the far-right led Jack to become a founding member of the Anti-Nazi League in 1977 – another example of Jack going out on a limb for his convictions and making national media headlines as a result.

Ultimately, it should not be any surprise that someone of Jack’s political persuasion contributed so much to the beautiful game. The fact is that there is a noble tradition of socialism and left-wing values running right through the timeline of English football; from Shankly, to Clough, to Ferguson. The relationship between socialism and football should be an obvious one. Football being played at its best perfectly mirrors a socialist vision for the functioning of society. Both involve an understanding that each and every one of us must work together to achieve a common purpose and that we are only as strong as our weakest link. Bill Shankly summed it up appositely by famously stating “The socialism I believe in isn’t really politics. It is a way of living. It is humanity. I believe the only way to live and to be truly successful is by collective effort, with everyone working for each other, everyone helping each other, and everyone having a share of the rewards at the end of the day. That might be asking a lot, but it’s the way I see football and the way I see life.”

It is in this tradition that Jack Charlton’s legacy must be firmly placed. Although he may never have articulated this point of view as explicitly and profoundly as Shankly did, Jack’s selfless actions, and the friends he resolutely and continually chose to stand alongside, spoke far louder than any words ever could.

Article Patrick O Donoghue, the outgoing Magazine Editor of the award-winning University Times, a recent graduate of Trinity College Dublin

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands