Guest post by Dr Duncan A. Heining, Long post warning…

The “Hold-your-nose” Election

If pollsters’ and pundits’ predictions prove accurate, on Thursday 4th July voters will return Labour to power with a massive majority…

In the latest issue of New Left Review, Oliver Eagleton notes an array of centrist chatterers who project onto Starmer, a political chameleon if ever there were one, their differing hopes for a new ‘Ukania’. Such voices aside, it is difficult to find much enthusiasm anywhere for the current leadership’s shop-soiled Blairism. Perhaps twenty or thirty years from now, historians will, with justification, dub this the “Hold-your-nose” election.

Since 1945, for nearly eighty years, the Conservative and Labour parties have traded places, with the latter successfully positioning itself as the responsible left-of-centre option for voters and business interests. Yet, Labour has been in power for just thirty of those nine decades, while the Tories have dominated both the electoral scene and shaped the defining narrative of

British politics.

Our first-past-the-post electoral system offers few opportunities for third parties to emerge to challenge these two parties and their electoral machines. The one exception since World War II came in the 1983 election when sections of the Labour Right defected to form the Social Democratic Party and later the SDP-Liberal Alliance.

In that election, the Alliance came within 700,000 votes of out-polling Labour and split the anti-Tory vote. Despite its success at the ballot box, the Alliance was left with just 23 seats against Labour’s 209 and the Tories’ 397. This trend continued for the next three elections with the Alliance/Liberal Democrats polling strongly but failing to make a significant advance in terms of seats in parliament until the 1997 election. The Lib Dems’ participation in the austerity government of David Cameron from 2010-15 was followed by a significant decline in vote share and number of seats.

In Scotland, until its failure to win the independence referendum vote and more recent debacles over allegations of corruption, the Scottish National Party offered the best hope of a rupture in the UK political scene. Though its vote share was much lower than that of the Lib Dems, after the 2015 election the SNP became the dominant party north of the border and held three times as many seats in Westminster as Tim Farron’s Lib Dems.

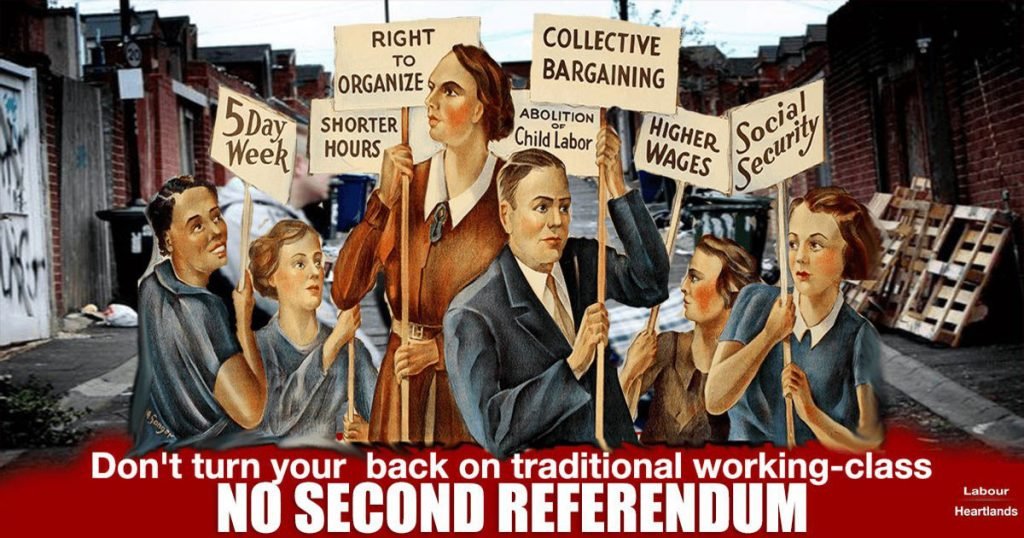

While perhaps only marginally to the left of Labour, its policies on climate change, opposition to nuclear weapons and success at the ballot box briefly seemed to suggest that more radical political change might have been possible elsewhere in Britain. In 2024, it seems likely that “red wall” voters who deserted Labour in 2019 over immigration and Brexit, not least due to Labour’s belated commitment to a second referendum, will return to the fold.

If recent Tory to Labour defections are indicative, “one nation’ Tories may also put their crosses by Labour’s rosette, while Labour seems also to have the backing of certain business interests. Once again, those party members on Labour’s left will no doubt do their bit to get the vote out.

As for the disenfranchised left beyond the party, indications are that some will vote Green seeing this as the progressive alternative. For the rest, it seems likely that they will back Starmer’s Labour, albeit with no enthusiasm. In effect, Labour is drawing its support from three or more distinct groups of voters.

While these groups may find common cause on issues such as NHS funding, even here there may be hidden differences between returning red wall voters driven by immediate concerns over waiting lists and GP access and those on the left more ideologically committed to what they see as the ideals represented by the NHS. Recent comments by Wes Streeting, Labour’s Shadow Health Minister, regarding “middle-class lefties” suggest that Labour is well aware of such differences between these two camps.

Other than such shared concerns, these camps reflect increasingly fractured political environments in the UK but also in North America and mainland Europe. Red wall voters will expect Labour to stop the boats and will baulk at any hint that Brexit is being abandoned, whereas for more liberal voters a renewal of ties with Europe is a major aspiration.

When it comes to action to slow climate change, the latter are likely to be just as disappointed. In fact, having deliberately ignored working class Labour supporters for three decades to its recent cost, it may well be that the Labour leadership will calculate that liberal and left voters will vote for it regardless given the absence of alternatives and, therefore, do not need to be appeased.

Discussions with any number of those on the left intending to vote Labour in 2024 reveal a curious mixture of resignation and loss on the one hand and willingness to suspend disbelief and ignore past experience on the other. This position seems predicated on an assumption that for all its past misdemeanours welfare lies at the heart of Labour’s mission. In reality, since the Second World War, Labour has been defined not primarily by commitments to welfare and equality but by its dedication to Atlanticism and the NATO Alliance.

This is the rock upon which the Labour left has foundered on the three occasions when its star was in the ascendant. In 1960, the Labour conference voted in favour of unilateral disarmament.

Labour’s leader of the time, Hugh Gaitskell, vowed to “fight, fight and fight again” to overturn the decision. The formation of the Campaign for Democratic Socialism (CDC) served as the vehicle through which Gaitskell and the Labour right-wing would reverse that decision in 1961 with backing from several trades unions that had previously voted in favour of the 1960 resolution.

Sixty years later, the Labour right mounted the most dramatic and protracted assault on the party’s leader in its post-war history. Jeremy Corbyn’s own front bench sought to embarrass him in the Commons, resigned on mass and called a vote of no confidence. When the latter failed, it charged the country’s most committed anti-racist parliamentarian with antisemitism. What was it about Corbyn that provoked such hostility?

Simply, the very idea of a Labour prime minister who was personally opposed to Britain’s membership of NATO, favoured unilateral disarmament and supported the struggle of Palestinian people against the West’s Middle-east stalking horse was more than reason enough. The second occasion when the Labour left was in the ascendant came forty years ago. The events surrounding the resignation of and formation of the Social Democratic Party by Labour’s so-called “Gang of Four” (Shirley Williams, Roy Jenkins, Bill Rogers, David Owen), Labour’s 1983 manifesto and the party’s defeat at the polls that year have entered British political mythology, a mythology that Labour’s right-wing have taken as their own.

Jenkins and Rogers had been leading figures in the CDC and the two main issues for the Gang of Four in leaving Labour and forming the SDP were Labour’s new commitment to unilateralism and to withdrawal from the European Economic Community. The 1983 election hung two mythic albatrosses around Labour’s collective neck; firstly, that the left split the Labour Party, secondly, that Thatcher’s victory was an emphatic one and that Labour’s defeat ensured another fourteen years of Tory government that was only ended by Blairism and the party’s turn to centrist pragmatism.

It was in reality Labour’s right-wing that split the party and the anti-Tory vote. The split gave Thatcher a one-hundred-and-forty-seat majority, not taking into account Northern Ireland’s Unionist parties. Labour lost some sixty MPs, with the Liberal/SDP Alliance taking, as noted, twenty-three. Examining the voting in more detail, however, reveals that the Tories took 42.4% of the popular vote, while Labour took 27.6% and the Alliance 25.4%. The figures become even more stark when the total vote is considered. Thirteen million people voted Tory with eight-and-half million votes going to Labour and nearly eight million going to the Alliance, a total of over sixteen million.

Moreover, the Tory vote actually declined with a 1.5% swing against the party. The election did, indeed, ensure a further fourteen years of high unemployment, the destruction of local government, the siting of US Cruise missiles on UK shores, increasing poverty for many and greater riches for the few, privatisation of public assets, the decline of manufacturing industry and the decimation of health, education and welfare. But blaming the Labour left for the failure is at least a partial distortion borne of right-wing media myth-making. It does, however, tell a story regarding what Labour is as a party, calling into question any claims it may make for itself as a socialist party or even today a social democratic party.

That is a story that many on Labour’s left – and on the left outside the party – are loath to analyse. With hindsight, Labour’s 1983 manifesto seems both radical and far-sighted. Setting to one side its intended departure from the EEC, that shibboleth of the liberal left, the party planned action on poverty, unemployment, rebuilding British industry, the NHS, housing, education, discrimination, racism and workers’ rights. Bearing in mind this was ahead of forty further years of climate change, Labour identified the urgent need to address environmental issues through conservation of energy. Admittedly, its commitment to fossil fuels seems less prophetic but confronting the climate issue was clearly central to the party’s plans to rebuild Britain.

Labour also acknowledged that a world beyond the North Atlantic existed and should inform any avowedly democratic socialist government’s policy considerations. And, of course, the party proposed to cancel Trident and disarm unilaterally, albeit retaining membership of NATO. On this, the manifesto notes,

“The next Labour government will maintain its support for NATO, as an instrument of détente no less than of defence. We wish to see NATO itself develop a non-nuclear strategy. We will work towards the establishment of a new security system in Europe based on mutual trust and confidence, and knowledge of the objectives and capabilities of all sides. The ultimate objective of a satisfactory relationship in Europe is the mutual and concurrent phasing out of both NATO and the Warsaw Pact. (my emphasis) The latter could hardly have gone down well in Washington.

Bearing in mind all that had gone before and has followed under Thatcher, Major, Blair, Brown, Cameron and various short-term occupants of No. 10, the manifesto seems admirably common-sensical. This did not stop Labour grandee Gerald Kaufman from describing the manifesto as the “longest suicide note in history”, an epithet trotted out by right-wing and centrist commentators ever since.

Forty years later, it seems party members will turn out to support a party that has shifted so far to the right that even its social-democratic credentials are highly questionable. Labour in 2024 is militaristic, supports an Apartheid regime in the middle east, is neo-liberal, is no longer committed to a mixed economy and on immigration is barely distinguishable from the Tories.

From the early seventies through to the mid-eighties, the radical left was effectively constituted within three camps each with their own particular strategy. Firstly, there were the two Trotskyist groupings, the International Socialists (IS; later the Social Workers Party SWP) and the Workers Revolutionary Party (WRP). These groups focused on building a base within the working class through the trades unions, while also being active in colleges and universities.

The second grouping includes the other two Trotskyist organisations, the Militant Tendency and, to a lesser extent, the International Marxist Group. Both pursued entrist strategies within the Labour Party, seeking to capture the party through its internal structures. These groups’ success can possibly be seen in Labour’s 1983 manifesto. The third group that can be identified is the more traditional Labour left. Its strategy focused primarily on winning conference votes and control of Labour’s NEC. As well as the part it played in relation to the 1983 manifesto, it also had some success in establishing strong bases in local government, most notably in London and on Merseyside offering an alternative vision of metropolitan, multi-cultural socialism.

The defeat of the miners in 1984 was followed by the failure of industrial action by print- workers in 1986, with disastrous consequences for the UK press and its control by the press barons. Of even greater significance was the decline in union membership between 1980- 1987 as a consequence of unemployment and a sharp decline in UK manufacturing. This decline had major implications for the extra-parliamentary left and its trades union-focused strategy.

The defeat of Labour at the polls in 1983 had similar consequences for the entrists, as did the expulsions of Militant activists by the Labour Party between 1983-1991. As to the traditional Labour left, the 1983 defeat was compounded by the abolition of the GLC and Thatcher’s targeting of Labour’s municipal bases. In effect, by 1987 all three camps were strategy-less. For the extra-parliamentary left this meant increasing isolation, for the Labour left it meant turning out the vote for Kinnock in 1987 and 1992 and for Blair in 1997.

Despite these setbacks and the halving of Labour membership after the Iraq and Afghanistan invasions, hopes that the Labour Party might yet be transformed into a radical socialist party continued amongst certain sections of the left. These were further catalysed by the election of Jeremy Corbyn in 2015, an event that seemed to coincide with the emergence of a similar opposition movement around Bernie Sanders in the U.S.A. and the rise of similar democratic socialist movements in Spain, France and Germany.

Given the failure of the UK left’s various strategies, it is important to remember that Corbyn’s approach was not just about capturing the party. Indeed, his base in the parliamentary party and in the party’s structures was, as it proved, very weak. The strategy, as with the other examples above, involved building a mass movement. Corbyn’s defeat can be seen as both an indication of the limitations of the strategy when faced with battles on all sides but, paradoxically, its potential viability.

The fact that the party’s right-wing was forced to escalate its attacks after Theresa May’s snap election in 2017 and Labour’s comparative success is, arguably, indicative in this respect. Of course, these attacks and accusations had their effect electorally but what really did for Labour in 2019 was abandonment of collective responsibility by Starmer and even Corbyn allies like Diane Abbott and John McDonnell in calling for a second EU referendum.

Effectively, Labour told those in red wall seats who had voted to leave the EU their votes did not count. There are lessons for the left, both inside and outside the party to learn from this, as well as from their previous collective histories. Sadly, this election offers a closer parallel to 1997 than 2017 in all regards with leftists willing to hold their noses and vote for second-hand Blairism.

Arguments for voting Labour amongst those otherwise disaffected take the form of statements to the effect “Labour is better than the Tories”, “Labour is less worse than the Tories”, that hardy perennial from party members “We can’t do anything if we can’t get elected” and “I’m not voting for Labour, I’m voting to get the Tories out.” The latter is not, of course, an option on the ballot paper. A vote for Labour is a vote for the party as it is and for its policies as they are.

Such sentiments are truly a counsel of despair. That Labour may spend more on health and education is true but it will also replace Trident, boost spending on armaments and increase its commitment to an expansionist NATO. Its policies on asylum seekers are profoundly reactionary and designed to appease racists amongst its own supporters.

It has no plans to confront the issue of press reform and is back-pedalling on its policies on the environment. It is no longer committed to abolition of the Lords or reform of the city, now the money-laundering capital of the world. Better than the Tories? Really?

Labour’s big problem will come when comes face to face with the conflicting demands and expectations of the motley constituency it has cobbled together to vote its way on July 4th, 2024 from red-wall voters, liberal metrosexuals, trades unionists, disgruntled one-nation Tories and disillusioned but homeless leftists.

Even hopes shared between these different camps such as increased funding for health and education may prove hard to meet given Labour’s refusal to raise the funds through taxation and its commitment to renewal of Trident and increased military expenditure.

As to who will benefit from the potential disillusionment should Labour fail, the fear must be that, as elsewhere in the developed north-western quartile of the globe, that it will be the far right. This a point well made by Yannis Varoufakis in the recent issue of New Internationalist. 2 Implicit in his argument is that such trends are almost inevitable given the absence of an organised left alternative.

Nor will Labour’s policy of appeasing the racists stop the rise of such as Farage, Reform UK and worse. Since the 2010 defeat at the polls, any number of leading Labour politicians from David Miliband, through Andy Burnham, Alan Johnson, Margaret Hodge, Ed Balls to Harriet Harman have trumpeted the line, “We got it wrong on immigration.” The line has not stopped the rise of the right any more than Labour’s 1968 volte face on immigration controls stopped the National Front.

It is a fairly depressing scenario for those hoping to see a realignment of the left in British politics or elsewhere. It seems that the possibility of the emergence of a British equivalent of Die Linke or La France Insoumise is forever precluded by our electoral system. Such a view, however, is more a consequence of the narrow frames of reference within which the British left operates as actual political reality.

It does not help, of course, that what opposition there is coalesces around a range of groupings such as Left Unity, People’s Assembly, the Green Party and campaigning groups such as Stop the War, CND and Extinction Rebellion.

In many ways, these groups and their success in mobilising huge numbers behind specific issue causes such as Israeli genocide in Gaza, austerity, imperialist wars in the Middle East and climate change indicate that a substantial constituency for radical economic, social and political change exists.

The scale of recent demonstrations is far greater than those that took place against nuclear weapons in the sixties/seventies, against the Vietnam war in the sixties and the poll tax in the eighties. The Greens mobilised around a million voters in the 2019 election and are likely to increase their vote significantly, if recent local elections are any predictor.

Add to this the million-and-a-half followers of Jeremy Corbyn on social media and we are looking at several million voters in the UK who reject, in potential at least, what is on offer from Labour. So, what is it that stops these individuals from forming a new party along, at least, democratic socialist lines?

The first answer lies in serious theoretical failures and an unwillingness to learn from history. On the one hand, the extra-parliamentary left has failed to theorise adequately its relationship with the Labour’s left, relying instead on strategies forged in hugely different circumstances in Tsarist Russia.

On the other hand, Labor’s left has failed to theorise its relationship with those outside the party. “Join us and change the party from within” founders for many of us on even a cursory reading of the history of the Labour left and of the Labour Party itself. The second answer to this question lies in the word ‘individual’.

While we come together to campaign on specific issues, most recently the Israeli invasion of Gaza, we do so only in that respect, and are otherwise isolated from each other. Despite the left’s success in mobilising huge numbers around specific single issue campaigns, there has been a consistent failure to broaden these struggles.

The third answer relates to the nature of these campaigns and their focus, which is ostensibly to change government policy by taking the moral high ground and winning the propaganda war.

The leadership of Stop the War, to take one example, are certainly not naive and are no doubt aware of the forces arrayed against them. They will recognise that the ultimate success of such campaigns requires radical political change of the existing order, not merely getting the right or rather left people into power.

This is not to suggest cynicism on their part but rather recognition of the contradictions of operating both within and against the system. Sadly, this isolation and separation between different groups with clearly overlapping goals finds them in a universe as minor planets orbiting a sun yet to burn brightly.

Their isolation is itself compounded by a focus on electoral politics where their capacity to influence is severely limited and, even if successful, will see any prescriptions watered down to appease business and media interests in the first place and more reactionary

sections of the electorate in the second. Perhaps there are other factors that limit the possibility of a realignment of the left that might lie in our collective psychology. Is there also a residual loyalty and psychological attachment to notions of a social democracy that served so many of us, now in our fifties, sixties, seventies and eighties so well It gave us the NHS, education and, for some, university degrees and free dentistry, not to mention the products of consumerism.

Moreover, those of us who purported to reject capitalism and indulged our Trotskyist fantasies of violent revolution in those years lost our innocence as large sections of the proletariat voted for Thatcher in 1979, 1983 and 1987.

Though there might have been other lessons that might have been learned from that loss, two were most immediately attractive – the focus on issues rather than grand transformations and, related to this, that some form of social democracy might be the best that might be hoped for.

For some, this would lead them into the Labour Party, albeit with the aspiration of aiding it in fulfilling its socialist destiny or returning it to its socialist path. This is a persistent trope one hears from those on the left of the party, despite all historic evidence that Labour is neither socialist, nor since Blair at least, social democratic. For some, it has taken them into the Green Party, for others, out of political activism and for the rest it has meant isolation and disillusionment.

Despite its size in potential, the radical left in Britain is isolated, trapped in an electoral vortex, torn between a hankering for a return to social democracy’s “golden age” between 1945 and 1972 and a vaguer hope that more might yet be possible. So, how might it extract itself from this vice? Obviously, some kind of coming together of groups such as Corbyn’s Peace and Justice Project, People’s Assembly, Compass, Left Unity, the Greens, the Labour Left and other such groupings is essential.

Without a core organisation or coalition, we remain isolated. There is also a need to offer a critique of Labour that examines its history critically not least in terms of the way its right-wing has remained so effective in dominating the party.

But also there is a need to identify as a force with common goals, to see ourselves constituted as such a force. The irony of the forthcoming election is that it offers just such an opportunity.

The slogan of IS/SWP at election times was “Vote Labour without illusions.” This had two

poles to it. Firstly, voting Labour was the more progressive alternative. Secondly, it was believed, that Labour’s failure to meet working-class aspirations would open doors to a more radical realignment within the class. I have dealt with the latter above. With regard to the former, Labour is no longer the “more progressive alternative.” That lot falls to the Green Party.

It is hard or at least pointless to argue against voting Labour where narrow majorities are in play but what of those seats where Labour is highly likely to win convincingly. Is it naïve to suggest that in such circumstances voting Green is the most effective way of keeping left wing hopes alive and even a small beginning in constituting ourselves as an effective force.

If that feels like a straw when a life raft is needed, we are where we are.

This was a guest post by Dr Duncan A. Heining.

Referencing…

1 Eagleton, O. “Stakeholder Capitalism Again” NLR 146 March/April 2024, p.

2 Yannis Varoufakis “The Problem is Capitalism” New Internationalist NI549 May/June 2024, p.29

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands