🎧 Audio: The Clay Cross Rebellion Article Podcast (MP3)

When Politicians and Councillors Were Comrades: Working for the People, by the People

A few miles down the road from where I sit, there’s a small former mining village in Derbyshire that most people have never heard of. Yet what happened there in 1972 should be taught in every school, discussed in every town hall, and remembered by every politician who claims to serve the people. Clay Cross. The name might mean nothing to you now, but it should. Because what happened there tells us everything about what democracy can be, and everything about what we’ve lost.

It’s a story governments would rather we forgot. A story about what happens when councillors and politicians actually keep their promises. A story that asks the most dangerous question in British politics: who do our elected representatives really serve?

In 1972, eleven Labour councillors in this Derbyshire mining town stood for election on a simple manifesto: for the people, by the people. They won overwhelmingly. Then they did something that now seems almost mythical in British politics.

They kept every promise they had made. For this act of democratic fidelity, for honouring the mandate given to them by their constituents, they were surcharged, bankrupted, and banned from public office. Their crime? Refusing to betray the people who elected them when Westminster demanded they increase council house rents by £1 a week, whilst unemployment in their town stood at 20 per cent.

Clay Cross Urban District Council’s rebellion against Edward Heath’s Housing Finance Act stands as a monument to a vanished political culture. But let us be precise about what has vanished. Not merely the willingness to fight (though that has certainly gone), but the fundamental understanding of who elected representatives serve.

The councillors of Clay Cross knew the answer with absolute clarity: they served their constituents, not their party hierarchy, not Westminster bureaucrats, not property developers or financial interests. They served the people who voted for them. Full stop…

This raises the most uncomfortable question in modern British politics, one we must ask again and again until we get a straight answer: who do our elected representatives serve? The people who elect them, or the party machines that select them? The communities they represent, or the lobbyists who wine and dine them? The citizens of their constituencies, or the globalist institutions that set the boundaries of acceptable policy?

At Clay Cross, the answer was never in doubt. Today, the evasions and qualifications flow freely, but the honest answer is rarely spoken.

Let me take you back to where this all began, because understanding Clay Cross’s roots illuminates how far we’ve fallen.

This was not some metropolitan borough of abstract ideals and Fabian essays. Clay Cross was a company town, born in 1837 when George Stephenson drove a tunnel under the village and discovered coal and iron. The Clay Cross Company owned everything. The pits. The houses. The workers’ lives. In 1882, an explosion at Parkhouse No. 7 pit killed 45 men and boys. Forty-five fathers, brothers, sons, gone in a moment of fire and gas. The inquest jury, composed of the local middle classes, found no negligence. They offered their “deep sympathy” to the bereaved.

Sympathy, as the workers discovered, paid no wages and filled no bellies.

But from those ashes, something else began to form. Solidarity.

Working people, stripped of everything but their labour and their pride, started to fight back. They organised, unionised, and politicised. They built a local Labour movement that didn’t come from London think tanks or university seminars. It came from the pithead and the picket line. From kitchen tables where families counted pennies and union halls where men planned strikes.

This wasn’t theoretical socialism. It was survival socialism. Democracy as a weapon of the poor.

Brannigan’s Jazz Band: twenty local miners, who toured the district in fancy dress during the 1922 nine-month coal strike, raising money from well-wishers.

The political response took time but it took root deep. By the early 20th century, Clay Cross had become a stronghold of municipal socialism. Labour held the council from 1894 to 1906, lost it, and regained it in the years after the First World War. By 1963, Labour won all eleven seats and would win every contest thereafter until the council’s abolition in 1974. But this was not the tired machine politics of entrenched power. It was active, politicised, embedded in the community.

Consider Councillor John Renshaw. In 1910, he led a 14-week strike against starvation wages. For his trouble, he was sacked and blacklisted. His comrades bought him a hawker’s cart so he could feed his family. Nine years later, he came back as a councillor. That’s what politics meant in Clay Cross. Representation born of struggle, not ambition. There were no photo ops, no consultancy contracts waiting at the end of service, no think-tank fellowships or seats on corporate boards. These councillors didn’t need to learn about working-class life. They lived it. They were it.

When Dennis Skinner, his brothers and comrades stood for election, they did so on that manifesto: for the people, by the people. Not for the party leadership. Not for corporate interests. Not for the international financial system or the demands of “modernisation” and “reform” that always seem to mean ordinary people getting less whilst the wealthy accumulate more. For the people, by the people. The voters of Clay Cross took them at their word and returned all eleven Labour councillors.

Then came the reckoning. Would these councillors, like so many before and since, discover that their manifesto was merely aspirational, subject to the “realities” of power? Would they, like generations of Labour politicians, explain that circumstances had changed, that compromises were necessary, that the people needed to understand the constraints under which modern government operates?

They did not. Instead, they governed exactly as they had promised. The council’s record stands as an indictment of every politician who claims that manifesto pledges are merely suggestions, guidelines to be abandoned when inconvenient. By 1950, Clay Cross had built 290 new homes, replacing slums where families lived in one-up, one-down hovels with “blind backs” and no indoor sanitation. Under Skinner’s leadership from 1960, the council transformed what local government could mean. They ran playgroups and Darby and Joan clubs. They gave free bus travel to pensioners and disabled residents in 1971, decades before it became national policy. They built an Olympic-sized swimming pool to replace the crumbling one at the Miners’ Welfare.

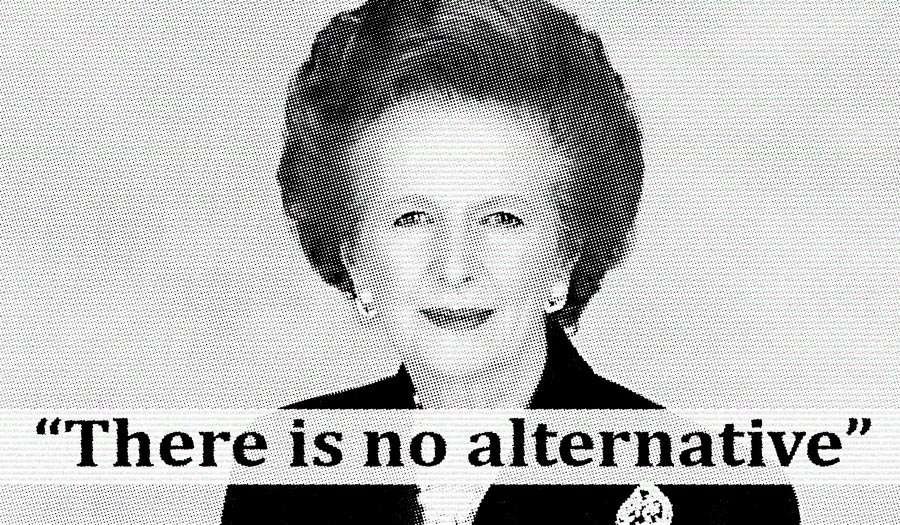

When Margaret Thatcher tried to snatch free school milk from primary school children in 1971, Clay Cross Council kept supplying it, funded by a penny rate and the chairman’s diverted allowance. Who did they serve in that moment? The Education Secretary’s diktat, or the children of their town? The answer was never in doubt. In 1973, they went further, providing free TV licences to elderly and disabled residents. Imagine that. A council that took money from its own budget to ensure pensioners could watch television without worrying about the cost. Not because some Whitehall policy document recommended it, not because it would look good in a press release, but because it was the right thing to do for their people.

Most crucially, Clay Cross understood housing as what Councillor Renshaw had called it in 1931: a right, not a commodity for private profit. This is the heart of the matter. Housing is not a speculative asset, not an investment vehicle, not an opportunity for developers and landlords to extract wealth from working people. It is a human necessity, and in a decent society it is the responsibility of democratic institutions to ensure everyone has a home.

By 1972, the council’s rents, at £1.65 a week including rates, were the lowest in Britain. Arrears were not pursued through the courts but by personal visits from the housing committee chair and vice-chair, who often found tenants unaware of benefits they could claim. The approach was effective and humane. It was also, by the standards of every government since, unconscionable.

Here is where the fundamental question becomes unavoidable. The Housing Finance Act of 1972 demanded that all councils raise rents by £1 a week, a 50 per cent increase. Heath’s Conservative government, responding to the pressures of international finance and the demands of fiscal orthodoxy (sound familiar?), decided that council tenants should pay more regardless of their ability to do so. Forty-six councils initially refused. Who were these councils serving when they refused?

Their constituents, who faced unemployment and poverty. But threatened with the appointment of housing commissioners and legal sanctions, 45 eventually complied. When the pressure came, when Westminster made clear that defiance would have consequences, these councils answered the question of who they truly served. They served the government. They served the system. They served everyone except the people who had elected them.

Clay Cross refused. They weren’t being rebellious for the sake of it. They were standing by their people. They knew that a community built on low wages couldn’t afford “fair rents” dictated by London accountants.

So they simply said no.

That word, simple, defiant, dangerous, still echoes down the decades.

Because when Clay Cross said no, they weren’t just refusing a rent increase. They were refusing the very idea that democracy means obedience.

They were reminding Britain that elected representatives are supposed to serve the people who put them there, not the bureaucrats, not the bankers, and not the party leadership.

It was, in every sense, a rebellion of conscience.

Clay Cross stood alone.

The Reckoning: When Conscience Met the State

“The men and women who were elected to serve on the council were not remote figures who did what the bureaucrats told them to do, but representatives of the working people of the town who kept faith with their electors. It was as simple as that.“

In September 1972, the councillors met and passed a motion rejecting every clause of the Housing Finance Act. They would not implement rent rises. They would not betray their voters. They would not become the agents of Whitehall against their own people.

That wasn’t rhetoric, it was conviction. These councillors didn’t speak the language of “difficult choices” or “realistic compromises.” They spoke plainly, as representatives of the people who had elected them. They knew who they served.

And when the government’s commissioner, a bureaucrat named Skillington from Henley-on-Thames, arrived to enforce the new rents, the Clay Cross councillors showed him exactly what local democracy looked like.

They refused him an office. Refused him a desk. Refused him a chair. Refused him even a pencil.

The tenants backed them all the way. They weren’t duped, misled, or manipulated, as the press claimed; they were standing with their councillors, defending their community. For months, the commissioner collected nothing. The rebellion spread from the council chamber to the streets, where solidarity still meant something.

Skillington withdrew months later, having collected nothing.

The rebellion was total. It was also doomed.

In July 1973, the eleven councillors were dragged before the courts, charged with “negligence and misconduct.” Their punishment was swift and merciless. They were surcharged nearly £7,000 each, a fortune for working people, and banned from holding public office.

Arthur Wellon, Charlie Bunting, Graham Smith, Eileen Wholey, George Goodfellow, Terry Asher, David Nuttall, David Percival, Roy Booker, David Skinner, and Graham Skinner. Eleven names that should be carved into the memory of every socialist in Britain.

Working men and women, good trade unionists, representatives who kept faith with their electors. Bankrupted for honouring their manifesto pledges. Destroyed for serving the people rather than the state.

“I don’t think for one bloody minute we are heroes. I think we are doing our job – and that’s to help the working class, the cream of the nation.” – Charlie Bunting

When the by-elections came in February 1974, the people of Clay Cross answered with defiance of their own. Ten of the “second eleven” Labour candidates were elected on the same manifesto: for the people, by the people. The eleventh lost by just two votes. Even after their champions had been destroyed by the state, the people refused to submit.

But history has a cruel sense of timing.

Four weeks later, Clay Cross Urban District Council was abolished in the government’s reorganisation of local authorities. North East Derbyshire Council took over and immediately raised the rents. The rebellion was over. The government had won, on paper.

Yet, as Graham Skinner said years later, it was a “futile gesture” that had to be made. Because democracy, if it means anything, must allow elected representatives to serve the people, even if it means breaking unjust laws.

The eleven councillors of Clay Cross lost their seats, their savings, and their livelihoods. But they kept something far greater: their integrity.

They proved that local government could still be government of the people, by the people, for the people. And that’s why the establishment had to break them. Because if Clay Cross had succeeded, if one small mining town had shown that working people could govern themselves, it would have lit a fire that no act of Parliament could ever extinguish.

The Lesson for Today: Who Do They Serve?

The great lie is that politicians serve the people. Once their backsides hit those green benches, they serve lobbyists and corporations. The green was meant to symbolise the common land and the common people. Now it’s the colour of money, and their conscience has faded with it.

Half a century has passed since Clay Cross. The pits are gone, the unions are hollowed out, and the language of solidarity has been replaced with soundbites about “growth,” “investment,” and “fiscal credibility.” But the same question that defined 1972 still haunts every council chamber and every Parliament bench in Britain: who do they serve?

Clay Cross councillors knew the answer. They served their neighbours, not the market. They served the tenants, not the Treasury. They served the working class, not the property speculators. When Westminster ordered them to betray their people, they refused. And for that, they were punished.

Compare that courage to today’s Labour Party, the party that once carried the torch for men and women like those of Clay Cross. Now it manages decline. It implements cuts with a smile and calls it “responsibility.” It sells off public land to developers and calls it “regeneration.” It quotes “fiscal rules” while foodbanks multiply. It sends out press releases about “values” while its councils partner with the same corporations that bleed communities dry.

When Clay Cross defied Edward Heath’s Housing Finance Act, they were accused of recklessness. When today’s Labour councils implement Tory cuts, they call it prudence. The roles have reversed, but the cowardice has stayed the same.

The councillors of Clay Cross understood something modern politics has forgotten: democracy is not obedience. It is representation. When you are elected on a manifesto, you keep your word, even if it costs you everything. Otherwise, what you have isn’t democracy at all, it’s management.

Look around Britain today and ask yourself: who is serving the people? When local councils close libraries, sell off housing, privatise care, and raise council tax to fund consultants, whose interests are being protected? When Labour MPs vote for foreign wars, for privatisation, for austerity, who are they representing?

Certainly not the people who elected them.

The people of Clay Cross knew what solidarity meant. They knew the difference between principle and performance. They voted for councillors who would fight for them, not climb over them. And those councillors kept their promise. They may have lost their seats and their livelihoods, but they kept their integrity, and in doing so, they preserved the one thing money and power can never buy: moral authority.

Clay Cross stands as a monument to the last generation of working-class democracy in action. It was the moment the establishment realised it could never again allow the people to govern themselves. And so, over time, local democracy was hollowed out, replaced with managerial politics, PR, and careerism. The Labour Party, once the movement of the common people, now sits comfortably in the boardrooms it was meant to challenge.

Tony Benn once said that to understand power, you must ask five questions:

- What power have you got?

- Where did you get it?

- In whose interests do you exercise it?

- To whom are you accountable?

- And how can we get rid of you?

He warned that if you cannot answer those questions, you do not live in a democracy but under tyranny.

But in this age of hollow politics and corporate capture, there is a sixth question we must now add, one that echoes from the coal dust of Clay Cross to the corridors of Westminster:

“Who do you serve?”

If politicians cannot answer that question with honesty, if they cannot look the people in the eye and say, “We serve you” , then they have no right to govern.

The councillors of Clay Cross broke the law to keep their word. Today’s politicians break their word to keep their careers. That is the difference between comrades and careerists, between democracy and deceit.

Until we once again find representatives willing to risk everything for the people who elect them, to stand against Westminster when Westminster stands against the people, our politics will remain hollow.

The rebellion at Clay Cross may have been crushed, but its spirit endures.

And it whispers still, from the coal dust and the council chambers of history:

For the people. By the people. Always…

Special thanks to Municipal Dreams

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands