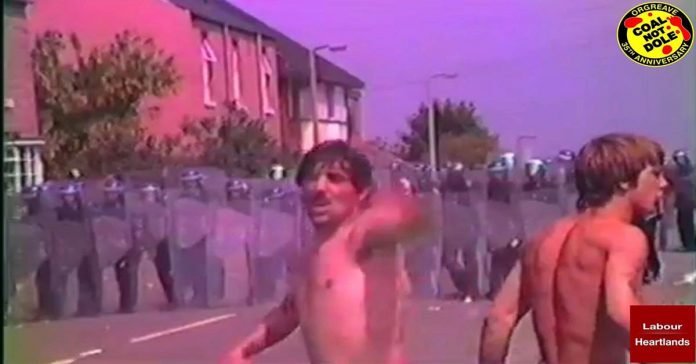

Monday 18 June 1984 was the most violent day of the year-long miners’ strike.

On that fateful day in June 1984, a clash of epic proportions erupted outside the Orgreave Coke works near Rotherham. Thousands of determined pickets faced off against a massive deployment of 5,000 officers brought in from all corners of the country.

The ensuing Battle of Orgreave, widely regarded as one of the most violent confrontations during the year-long miners’ strike, left an indelible mark on the collective memory of the mining community.

Amidst the chaos and brutality, 95 individuals found themselves charged with riot and violent disorders. However, the cases against them soon crumbled under the weight of doubt surrounding the reliability of police evidence.

Allegations of excessive violence by the officers tasked with policing the picketing were further compounded by the shocking revelation that fabricated accounts tainted the subsequent investigation.

The demand for a public inquiry into the events that transpired at Orgreave has been fervent and unwavering. Campaigners, united under the Orgreave Truth and Justice Campaign (OTJC), seek the truth that has been shrouded in years of lies and cover-ups. They tirelessly advocate for an inquiry to uncover the full extent of the Conservative government’s role in the policing of the strike.

However, in 2016, then-Home Secretary Amber Rudd dashed hopes of justice when she categorically ruled out a public inquiry. Her reasoning? “Ultimately there were no deaths or wrongful convictions” resulting from the events of 1984. Such dismissive remarks not only trivialize the significance of the Battle of Orgreave but also undermine the urgent need for accountability and closure.

The miners who stood united outside that coking plant in Orgreave, South Yorkshire, have long maintained that they faced a military-style operation designed to suppress their cause. Their cries of police brutality and orchestrated attacks have resonated for decades. The OTJC’s tireless pursuit of truth and justice echoes their unwavering commitment to unmasking the events that transpired on that fateful day.

The Battle of Orgreave stands as a sombre reminder of the abuses of power that can occur when the state confronts its citizens with excessive force. It is a stain on the fabric of justice, where narratives were manipulated and truth distorted. The call for an inquiry is not just about setting the historical record straight; it is about acknowledging the suffering endured by those who fought for their rights and demanding accountability for those who abused their positions of authority.

As the Orgreave Truth and Justice Campaign persists in their fight for an inquiry, they expose the web of lies and cover-ups that have cast a dark shadow over this chapter in British history. The battle for truth and justice is far from over. It is a battle that demands unwavering support, for it is a battle against the erosion of accountability and the safeguarding of our collective memory.

The Battle of Orgreave must not be consigned to the annals of forgotten struggles but rather elevated as a symbol of our resolve to uncover the truth, no matter how long it takes.

What happened at Orgreave

The miners wanted to stop lorry loads of coke leaving for the steelworks. They thought that would help them win their strike, and help protect their pits and their jobs. The police were determined to hold them back.

The number of officers was unprecedented. The use of dogs, horses and riot gear in an industrial dispute was almost unheard of. Some of the tactics were learned from the police in Northern Ireland and Hong Kong who had experience dealing with violent disorder.

During the subsequent court case, a police manual was uncovered which set out the latest plans to deal with pickets and protests.

Police vans and Range Rovers were fitted with armour so they could withstand the stones being thrown by some in the crowd. The miners suspected the whole operation was being run under government control.

Many believe Orgreave was the first example of what became known as “kettling” – the deliberate containment of protesters by large numbers of police officers. It marked a turning point in policing and in the strike.

It was the moment the police strategy switched from defensive – protecting collieries, coking plants and working miners – to offensive, actively breaking up crowds and making large numbers of arrests. In many mining communities faith in the police was destroyed, a legacy that lasts to this day.

There were questions in court about the reliability of the police evidence. Many of the statements made by officers were virtually identical. At least one had a forged signature.

Eventually, the case was thrown out and the arrested miners were cleared.

The miners had been set up.

They believed the intention that day was to beat them and make arrests, a show of force that would convince them they were not going to win.

That left a bitter legacy of hatred and distrust of the police in many mining communities.

The police said they were just doing their job in the face of violence from striking miners. The strike lasted until March 1985.

Hundreds of mines closed afterwards and many miners faced redundancy. Even the Orgreave coke works itself has now gone. Houses and a business park are now gradually taking over the site.

The Orgreave Coking Plant, now demolished, stood on the outskirts of Sheffield, just 7 miles from Hillsborough Stadium, scene of the Hillsborough disaster on 15th April 1989, in which 96 Liverpool supporters were, has the jury at the recent inquests determined, unlawfully killed. The plant supplied coke to the power station at Scunthorpe some 20 miles away.

Short history

In March 1984 the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) launched a national strike in response to the plans of the National Coal Board (NCB) to close a number of pits. The NCB claimed that it only wanted to close 20, but the NUM maintained – and subsequent events proved them right – that more than 70 pits were on the NCB’s hit-list. In the decade after 1984, the coal-mining industry was effectively destroyed, with devastating consequences for the miners, their families and their communities.

The NUM called for a mass picket outside the coking plant on 18th June 1984, aimed at disrupting the supply of coke from Orgreave to Scunthorpe. It followed a series of smaller demonstrations at the plant in May and early June. Whereas in the first three months of the strike police forces around the country had done their utmost to prevent would-be pickets from reaching the colliery where they planned to demonstrate, on this occasion, 18th June, the police fell over themselves to be “helpful”, guiding and ushering miners to the site, in particular to the “topside”, the field to the south of the Plant.

Many of the pickets were surprised by this unusual display of police courtesy, and some were – rightly, as it turned out – suspicious. The “topside” was a field bounded at its bottom by a cordon of police officers six and more deep, blocking access to the plant; the two sides were patrolled by dog-handlers with their charges, and a steep railway embankment and railway lines marked the back of the field. The only real escape route was over a narrow railway bridge at the top corner of the field, and this led into Orgreave village, with domestic housing on the right and a small industrial estate to the left.

THE BATTLE OF ORGREAVE

What happened on 18th June 1984 was not a battle but a rout. In the lull that followed a number of what were by then ritual but ineffectual pushes against the police lines, the officer in charge of the police operation, Assistant Chief Constable Clement, ordered the police lines to open. Dozens of mounted officers, armed with long truncheons, charged up the field, followed by snatch squad officers in riot gear, with short shields and truncheons. The miners fled up the hill towards the embankment and the railway bridge. Many of those who couldn’t or wouldn’t run were assaulted with batons, causing several serious injuries, and dragged back through the police lines to the temporary detention centre opposite the plant.

Several similar charges followed, forcing the miners up into the village, where they tried to find refuge in gardens and in the yards of the industrial units opposite. The police ran amok, clubbing and arresting miners indiscriminately. In one piece of TV footage a senior officer can be heard shouting “bodies, not heads”, but the number of head injuries sustained by the miners meant he was largely ignored.

It was a miracle no-one was killed. One officer was seen on television straddling a defenceless miner on the ground and battering him repeatedly about the head with his truncheon. Because the incident was witnessed by millions on TV, South Yorkshire Police interviewed the officer, PC Martin from the Northumbria force, two days later. PC Martin said: “It’s not a case of me going off half-cocked. The Senior Officers, Supers and Chief Supers were there and getting stuck in too – they were encouraging the lads and I think their attitude to the situation affected what we all did.” The papers were referred to the Director of Public Prosecutions, who advised that PC Martin should not be prosecuted. There is no record of PC Martin being disciplined, either.

Altogether 55 miners were arrested at the topside, and all of them were charged with “riot”, an offence which at that time carried a potential life sentence. A further 40 men were arrested at the “bottom” (Catcliffe) side. They were charged with the marginally less serious offence of “unlawful assembly”.

The trial, May – July 1985

It was not until May 1985, almost a year later, that the case came to court. 15 miners, all charged with riot, appeared at Sheffield Crown Court in what was intended by the Prosecution to be the first of a series of trials. The trial collapsed after 48 days of hearings when the Prosecution abandoned the case. It became clear as the police witnesses trooped in and out of the court that many officers had had large parts of their statements dictated to them, and that many of them had lied in their accounts, claiming to have seen things they could not have seen, or that they had arrested someone they had not. One statement with a signature forged by a police officer simply disappeared from court over lunch-time, never to re-appear.

It also emerged in the course of the trial that new and unlawful public order policing tactics set out in a secret police manual had been used for the first time at Orgreave. At times the trail descended into farce, and the Prosecution, cutting its losses, dropped the cases of the remaining 80 miners.

There was never any investigation into the conduct of the police for assaulting, wrongfully arresting and falsely prosecuting so many miners, nor for lying in evidence. Not a single officer faced disciplinary or criminal proceedings. Five years later, however, and a year after the Hillsborough disaster, South Yorkshire Police agreed to pay a total of nearly £500,000 to 39 of the miners, without admitting that they had done anything wrong.

Why is Orgreave in the news now?

Because Orgreave and Hillsborough are part of the same story. Both cases have at their heart South Yorkshire Police, although Orgreave involved officers from many other forces as well. The Orgreave Truth and Justice Campaign (OTJC) is pressing for a full and independent inquiry into what happened, just as the Hillsborough campaigners demanded an impartial investigation into the causes of the Hillsborough disaster.

The Independent Police Commission (IPCC) decided in June 2015 that, partly because of its limited terms of reference, it would not carry out a full investigation into Orgreave, although its report contained some serious criticisms of the actions and attitudes of South Yorkshire Police, implicitly suggesting that a wider inquiry was called for.

Both cases, Orgreave and Hillsborough, involve serious wrongdoing by South Yorkshire Police: At Orgreave this involved the assaults, wrongful arrests and false prosecutions of the miners and perjury in court;

At Hillsborough, the inquest jury has now found that the 96 fans died as a result of criminally serious gross negligence by the police and that the police told widespread lies to try and unfairly blame the fans.

Both cases involve strikingly similar attempts by the police to manipulate the evidence:

After Orgreave junior officers have come forward and said that parts of their statements, supposedly their own personal recollection of events, were dictated to them by senior officers. Analysis of their statements shows that many do indeed contain lengthy identical passages – which cannot be a coincidence;

In the Hillsborough Inquest, many officers gave evidence that they were told not to write up their notebooks in the usual way, but instead to write updated statements on plain paper, which were then edited, often quite radically, by more senior officers and lawyers acting for the police.

Both cases involve the police colluding with the media to portray a false picture of events and blame the innocent so as to conceal their own wrongdoing and failings:

After Orgreave, encouraged by the police, the media unfairly vilified the miners for provoking the violence when in fact it was the police who instigated it;

After Hillsborough, egged on by the police, the media unfairly blamed the fans for the disaster, accusing them of being drunk, arriving late and trying to get into the match without tickets, an account which the Inquest jury has now roundly rejected.

In neither case has there been any proper accountability for what the police did wrong.

There is a clear and direct chronological link between the two events:

The way in which the police abused their power at Orgreave, lied about it and got away with it, fostered the culture of impunity which allowed the cover-up after Hillsborough to take place.

Had the police lies after Orgreave has been properly and publicly addressed, the Hillsborough cover-up would never have been allowed to happen.

Why does Orgreave matter?

Orgreave represents one of the most serious miscarriages of justice in this country’s history, and it has never been adequately addressed. It is important that the truth is established and that the police are brought to account.

Many of the miners have been left with ongoing physical and psychological problems. Many lost their jobs and their marriages and were left with a sense of grievance at the unjust treatment that haunts them even today.

Orgreave led to a massive breakdown of trust in the police in the former mining communities (and indeed more widely) and this continues today among the children and grandchildren of the miners.

Orgreave marked a turning point in the policing of public protest. It sent a message to the police that they could employ violence and lies with impunity. It was only a year after Orgreave that the so-called “Battle of the Beanfield” took place, with violent and unprovoked attacks by the police on New Age travellers, followed by large-scale wrongful arrests. And more recently there have been examples of police “kettling” demonstrators in London for several hours – a kind of pre-emptive imprisonment. With the Government’s Trade Union Act aiming to further restrict picketing, the right to protest in public is in serious danger.

What needs to happen?

In December 2015 the Orgreave Truth and Justice Campaign provided the then Home Secretary, Theresa May, with a lengthy legal argument, calling on her to set up an independent public inquiry into the policing of events at Orgreave on 18th June 1984.

Such an inquiry could take the form of a panel-type inquiry, like the Hillsborough Independent Panel, which reviews all the documents, a full public inquiry that can call witnesses, or something in-between.

The Campaign wanted to discuss with Theresa May the scope and terms of reference of any inquiry set up.

By the time of the EU referendum vote, Theresa May had not made a decision on the legal submission despite growing pressure from OTJC, the media and supportive MPS. In the event, she was appointed Prime Minister in July 2016 and Amber Rudd became Home Secretary. An OTJC delegation met Amber Rudd in September 2016 for what the campaigners thought was a positive and constructive meeting where she gave a deadline for an announcement at the end of October 2016. But on this date, she announced there would be no investigation of any type on the grounds there had been no deaths, no convictions, no miscarriage of justice and no new lessons for current police force s to learn.

The Labour Party, under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn, has now made a firm commitment to an inquiry when a Labour Government is elected. This is on Page 80 of the Labour manifesto. We also have support from Frances O’Grady, General Secretary of the TUC and many Trade Unions, Councils, political groups and community organisations.

We ask all those who support our aims to join with the campaign and write to the current Home Secretary Sajid Javid, urging him to set up an inquiry without any further delay.

Where can I find out more?

Orgreave Truth and Justice website

Email:Orgreavejustice@hotmail.com

www.facebook.com/OrgreaveTruthAndJusticeCampaign

YouTube Films

Orgreave Justice: https://vimeo.com/148549592

Battle for Orgreave: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bKPWtA_YzfA&index=16&list=PLckigBFtiYQcd6iPGUS9p5zAF5iQLNw1b

Orgreave Truth and Justice campaign: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nfSPm6kZ1GM&index=2&list=PLckigBFtiYQcd6iPGUS9p5zAF5iQLNw1b

Lesley Boulton: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ggEug2JQZ7E&index=1&list=PLckigBFtiYQcd6iPGUS9p5zAF5iQLNw1b

Books

State of Seige by Jim Coulter, Susan Miller and Martin Walker (Canary Press, 1984)

The Enemy Within The Secret War Against the Miners by Seumas Milne (Verso, rev. Ed. 2014) Seumas Milne argues that the breaking of the miners’ union was the outcome of a concerted secret police campaign.

Settling Scores: The Media, The Police and the Miners’ Strike Granville Williams (www.cpbf.org.uk 2014) Explains the events which led to the setting up of the Orgreave Truth and Justice Campaign.

#Orgreave

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands