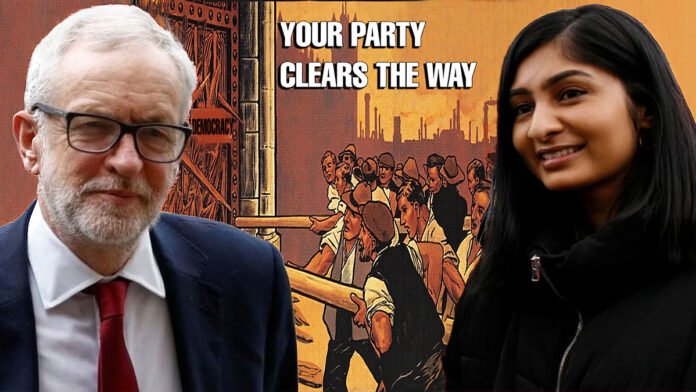

Your Party Clears The Way: Jeremy Corbyn and Zarah Sultana Launch a New Party

What does it mean when the most vilified politician in modern British history becomes the bearer of the nation’s democratic hopes? The answer arrived this week with Jeremy Corbyn’s confirmation that he and Zarah Sultana have launched a new political party, a development that should send tremors through every comfortable assumption about Britain’s managed democracy.

“It’s time for a new kind of political party. One that belongs to you.” With these words, Corbyn and Sultana have thrown down a gauntlet that the establishment hoped never to see again. After five years of exile, ridicule, and systematic character assassination, the man they declared politically deceased has returned to haunt the very system that expelled him.

The timing could hardly be more pointed. As Keir Starmer’s Labour government stumbles from one capitulation to another, refusing to scrap the two-child benefit cap while children go hungry, maintaining arms sales to Israel while Gaza is turned to rubble, promising nothing more ambitious than managerial competence, and yet still unable to deliver even that. While the country cries out for transformation, Corbyn offers what Westminster’s consensus has declared impossible: hope.

Their founding statement reads like a manifesto from another political universe, one where politicians dare to name the forces destroying ordinary lives. “The system is rigged when 4.5 million children live in poverty in the sixth richest country in the world,” they declare, cutting through the comfortable euphemisms that allow poverty to persist by describing it as “unfortunate” rather than “engineered.”

The policy platform sketched in their letter, mass redistribution of wealth, public ownership of essential services, massive council house building, an end to NHS privatisation, represents nothing less than a frontal assault on four decades of neoliberal orthodoxy. These are not the carefully focus-grouped policy nuggets designed to offend no one while changing nothing. They constitute a coherent alternative vision of how Britain might be organised if human need trumped corporate profit.

Consider the revolutionary simplicity of their core proposition: “It is ordinary people who create the wealth, and it is ordinary people who have the power to put it back where it belongs.” This sentence demolishes the fundamental mythology of contemporary capitalism, which insists that wealth trickles down from entrepreneurial elites rather than bubbling up from collective labour. In twelve words, Corbyn and Sultana have articulated what decades of academic analysis struggle to communicate.

The establishment’s response has been predictably hysterical. Already, the usual suspects are dusting off their familiar scripts about “hard left extremism” and “unelectable socialism.” They will resurrect every tired smear, every manufactured controversy, every fragment of the coordinated campaign that once reduced Corbyn’s approval ratings to sub-basement levels.

But something fundamental has changed since 2019. The policies that were dismissed as fantasyland extremism have been vindicated by events. Public ownership of energy companies seems less radical when private utilities extract record profits while households choose between heating and eating. Wealth taxes appear less outrageous when billionaires multiply their fortunes while food banks proliferate. Even Palestinian solidarity, once portrayed as the political equivalent of leprosy, now commands majority support among younger voters who refuse to accept genocide as the price of geopolitical stability.

Critics will argue, with considerable justification, that Corbyn’s previous leadership ended in electoral catastrophe and that returning to his brand of politics invites similar defeat. They will point to polling evidence suggesting that his personal approval ratings remain toxic, that his association with controversial positions on foreign policy alienates potential supporters, and that Britain’s first-past-the-post electoral system makes new party formation an exercise in futility.

These concerns deserve serious engagement rather than dismissive rhetoric. Corbyn’s 2019 defeat was comprehensive, his handling of antisemitism allegations was clumsy, and his communication of complex positions often proved inadequate to the task of countering hostile media narratives. The electoral mathematics facing any new left-wing party remain daunting, particularly given the resources and institutional advantages enjoyed by established parties.

Yet these pragmatic objections miss the deeper currents reshaping British politics. Labour’s rightward march has created a vacuum where authentic opposition to austerity politics once existed. The party that once promised to transform Britain now struggles to articulate why anyone should vote for managed decline over unmanaged decline. Into this void steps a movement offering something Westminster’s consensus has declared extinct: genuine alternatives to the status quo.

The temporary name “Your Party”, with its promise of democratic participation in shaping direction, leadership, and policy, signals something genuinely novel in British politics. Rather than the usual top-down party formation, where established figures recruit supporters for predetermined programmes, Corbyn and Sultana propose bottom-up construction where ordinary members determine fundamental questions of organisation and purpose.

This approach reflects hard-won lessons from Corbyn’s Labour leadership, when grassroots enthusiasm repeatedly collided with institutional resistance from party machinery, parliamentary colleagues, and media gatekeepers. The new formation promises to embed democratic participation so deeply into its DNA that such betrayals become structurally impossible.

The policy directions outlined in their founding letter, from wealth redistribution to Palestinian solidarity, represent more than electoral positioning. They constitute a coherent worldview that connects domestic inequality with international injustice, corporate power with environmental destruction, economic exploitation with political exclusion. This holistic approach distinguishes authentic left politics from the issue-by-issue reformism that characterises liberal alternatives.

Consider their treatment of migration and refugee issues, where they distinguish between legitimate concerns and deliberate scapegoating. While acknowledging that rapid population changes strain public services already weakened by austerity, and that security processes for undocumented arrivals require serious attention, they reject the fundamental premise that immigrants cause Britain’s structural problems. “The great dividers want you to think that the problems in our society are caused by migrants or refugees. They’re not. They are caused by an economic system that protects the interests of corporations and billionaires.”

The international dimensions of their platform, demanding an end to arms sales to Israel, supporting “a free and independent Palestine”, will inevitably provoke accusations of electoral suicide in a political culture that treats support for Palestinian human rights as evidence of extremist sympathies. Yet polling consistently shows majority support for arms embargoes and ceasefires, suggesting that Westminster’s consensus on “unconditional support for Israel” represents elite opinion rather than public sentiment.

The broader significance of this launch extends beyond immediate electoral calculations. For five years, Britain’s political establishment has operated on the assumption that Corbynism represented a temporary aberration, quickly corrected by electoral defeat and internal party purges. The emergence of this new formation suggests that reports of democratic socialism’s death were greatly exaggerated.

More fundamentally, Corbyn and Sultana’s party represents a challenge to the managed democracy that has characterised Britain since the Thatcher era. The carefully maintained consensus that There Is No Alternative to market fundamentalism faces its most serious challenge since the miners’ strike, articulated by politicians who refuse to accept the boundaries of acceptable discourse.

The response from established parties will prove instructive. Labour will likely dismiss the new formation as irrelevant while simultaneously adopting policies designed to prevent defections. The Conservatives will welcome any development that might split the anti-Tory vote. The Liberal Democrats will position themselves as the sensible centre between extremes, despite their own record of enabling austerity politics.

But the real test will come in next year’s local elections, where the new party plans to field candidates. Success in these contests would demonstrate that appetite for authentic alternatives extends beyond social media echo chambers into actual voting behaviour. Failure would vindicate critics who insist that British voters prefer managed decline to transformative change.

The stakes could hardly be higher. If Corbyn and Sultana succeed in building a sustainable political alternative, they will have proven that democratic socialism remains viable in contemporary Britain. If they fail, the established parties will have confirmation that neoliberal consensus enjoys unshakeable electoral dominance, regardless of its policy failures or moral bankruptcy.

The path forward requires recognition that this development represents more than ordinary political competition. The emergence of a genuinely left-wing alternative poses existential questions about the nature of British democracy and the possibility of fundamental change within existing institutional frameworks.

We must demand that media coverage engage seriously with the policy proposals rather than retreating into familiar character assassination, as the Observer tried recently. We must insist that electoral debates address substantive questions about wealth distribution, public ownership, and international justice rather than dissolving into personality-driven theatre.

Most crucially, we must recognise that the success or failure of this venture will depend not on the personal qualities of its leaders but on the willingness of ordinary people to engage with democratic politics beyond the ritual of periodic voting. The promise of a party that “belongs to you” can only be redeemed through active participation in the hard work of political transformation.

The comfortable assumption that democratic socialism died with Corbyn’s 2019 defeat has proven premature. The movement that terrified Westminster into coordinating unprecedented campaigns of vilification has returned, tempered by experience and strengthened by vindication. Whether it can translate moral clarity into electoral success remains to be seen. But the very fact of its emergence proves that another world remains possible, even in the darkest corners of Britain’s managed democracy.

Real change, as they promise, is indeed coming. The question is whether we possess sufficient courage to embrace it when it arrives.

I confess a personal ambivalence toward this development that readers deserve to understand. While I wish Corbyn and Sultana’s venture every success, Britain desperately needs voices willing to challenge the suffocating consensus that has reduced politics to a choice between different flavours of managed decline. I cannot yet pledge my own allegiance to their cause. Too many fundamental questions remain unanswered.

Where do they stand on women’s rights in an era when basic biological categories face ideological assault? What is their position on European integration, given that the EU question continues to divide those who would otherwise unite against neoliberal orthodoxy? These are not peripheral concerns but defining issues that will determine whether any new formation can build the broad coalition necessary for meaningful change.

Until such clarity emerges, I shall support this party as I support the Workers Party and other genuinely socialist formations, from a respectful distance, applauding their courage while maintaining critical independence. What matters is not the specific vehicle but the direction of travel: toward politics that serves ordinary people rather than globalist elites, that prioritises community solidarity over market fundamentalism, that dares to imagine alternatives to the humanitarian and economic catastrophe masquerading as sensible centrism.

The comfortable assumption that democratic socialism died with Corbyn’s 2019 defeat has proven premature. Whether this phoenix can rise from those ashes remains to be seen, but the very attempt deserves our attention and, where warranted, our conditional support.

To join or support “Your Party” click the link below….

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands