Britain’s War Economy: £73bn for Defence, 7.3 Million on Waiting Lists

Here is a question that no one in polite political society seems willing to ask. If Russia cannot take a single Ukrainian city without three years of grinding attrition, a million casualties, and the near-collapse of its own conventional military, by what strategic logic is Britain being prepared for a generational war against the same opponent?

It is Valentine’s Day, 2026, and the Prime Minister is in Munich whispering sweet nothings to an audience of defence ministers, arms dealers, and transatlantic policy architects. The romance, however, is not with the British public. It is with a permanent footing of military readiness. “We must build our hard power,” Keir Starmer declared this morning, “because that is the currency of the age.” He said Britain must “be ready to fight.” He invoked the spectre of 1930s appeasement. He warned that anyone who dissents, whether from the left or the right, would bring about “division and then capitulation” and cause “the lamps to go out across Europe once again.”

Let us pause on that phrase. It was first spoken by Sir Edward Grey on the eve of the First World War, a conflict that killed 20 million people, destroyed four empires, and solved precisely nothing. That Starmer reaches for this rhetoric so casually, at a conference bankrolled by defence contractors and attended by the very people who profit from escalation, should give every thinking person in Britain cause for alarm.

Because the question is not whether Russia poses challenges to European security. It does. The question is whether those challenges justify the wholesale transformation of Britain into a war economy, the gutting of foreign aid to the world’s poorest, the continued degradation of the National Health Service, and the creeping surrender of democratic sovereignty to supranational defence structures that no British voter was consulted about.

The evidence suggests they do not. What the evidence suggests is something rather more troubling: that Britain is being psychologically prepared to accept permanent militarisation, not because the threat demands it, but because the politics require it.

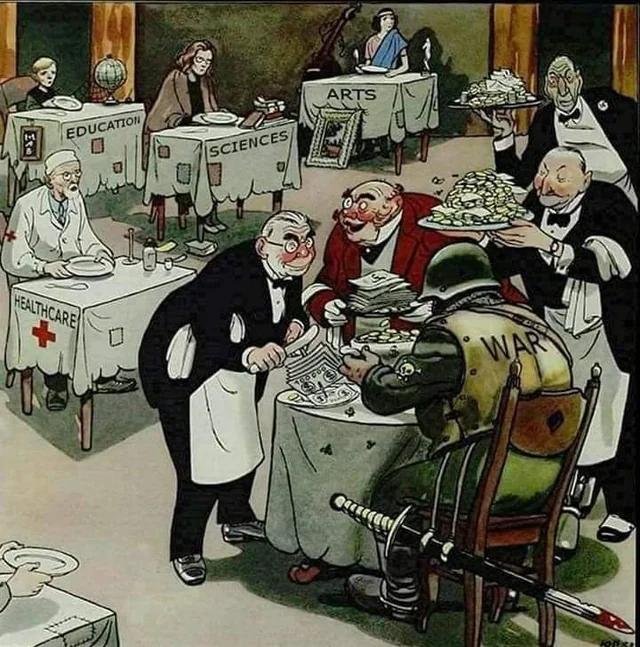

The most sinister aspect of a defence-focused industrial strategy, however, lies in its inherent incentive structure. When your economic model depends on arms production, you inevitably create pressure to sustain demand. And the demand for arms is war. An economy built on weapons manufacturing does not merely respond to threats; it requires them. It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, needing conflicts to justify its own existence and growth. The uncomfortable truth of the war economy is this: it only works when there are wars to fight.

And when the wars run out, the machine does not wind down. It goes looking for new ones…

The Russian Threat: Rhetoric vs. Reality

Starmer’s Munich address rests on a single foundational claim: that Russia presents a clear and growing military danger to Western Europe. “NATO has warned that Russia could be ready to use military force against the alliance by the end of this decade,” he told his audience. He asserted that Russian casualties number “well over a million” and yet insisted, in the same breath, that Russia’s rearmament “would only accelerate” even in the event of a peace deal.

Both things cannot be true simultaneously without serious qualification. And serious qualification is precisely what was missing from the speech.

Russia’s nominal GDP stands at approximately $2.5 trillion, making it the world’s eleventh largest economy. It is roughly equivalent to Spain and Portugal combined. Four individual European nations, Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy, each possess a larger nominal GDP. Combined, the European NATO economies outstrip Russia’s by a factor of more than ten to one. Starmer himself acknowledged this in Munich, calling Europe a “sleeping giant” whose economies “dwarf Russia’s more than ten times over.” One might ask, then, why the giant needs to militarise quite so urgently against an adversary it already dwarfs.

The military picture is equally revealing. Russia has sustained catastrophic losses in Ukraine. Its pre-invasion conventional force, which Western analysts once regarded as formidable, has been exposed as operationally brittle, logistically primitive, and incapable of executing complex manoeuvre warfare. A study published by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in 2025 noted that Russian forces remain unable to conduct effective joint operations, and that their reconstitution efforts emphasise mass over quality, rebuilding “bigger forces, not better forces.” At the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum in July 2025, Russia’s own Economic Development Minister admitted that the country was “on the brink of a recession.” An economic advisor to the Presidential Executive Office confessed that “the model that ensured growth in recent years has largely reached its limit.”

Does this describe an adversary poised to march on Berlin? Or Paris? Or London?

Even Trump’s own envoy, Steve Witkoff, when asked directly whether Russia intended to “march across Europe,” answered with two words: “100% not.” Britain’s Chief of the Defence Staff, Admiral Sir Tony Radakin, has stated publicly that Russia will not attack NATO.

The Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft concluded in a major 2024 assessment that Russia “likely has neither the capability nor the intent to launch a war of aggression against NATO members.”

None of this means Russia should be treated as benign. Its hybrid warfare activities, from undersea cable sabotage in the Baltic to disinformation campaigns, are real and demand robust responses. But hybrid threats are not existential military threats. Conflating the two, as Starmer’s speech systematically does, is not strategic communication. It is threat inflation. And threat inflation, in a democracy, has consequences.

The Deterrent Nobody Mentions

Buried beneath Starmer’s war rhetoric is an extraordinary omission. At no point in his Munich address did he substantively address the central strategic reality of European security: nuclear deterrence.

For seventy years, the doctrine of mutually assured destruction has prevented direct military confrontation between NATO and Russia. Britain possesses an independent nuclear deterrent. France possesses an independent nuclear deterrent. The United States, for all its current transatlantic ambiguity, possesses the largest nuclear arsenal on earth. Starmer himself announced in Munich that Britain is “enhancing nuclear cooperation with France” and reminded his audience that the UK “has been the only nuclear power in Europe to commit its deterrent to protect all NATO members.”

So the deterrent exists. The deterrent works. The deterrent is being enhanced.

If that is the case, then the argument for conventional military build-up on a generational scale requires a much higher burden of proof than was offered in Munich. The purpose of nuclear weapons is precisely to render large-scale conventional aggression between nuclear powers suicidal. That has not changed. What has changed is the political usefulness of pretending otherwise.

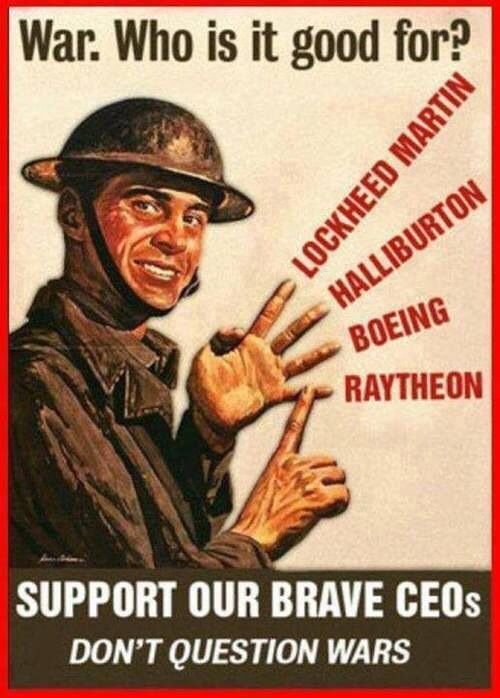

Follow the Money

When a politician tells you that hard power is “the currency of the age,” it is worth asking who is doing the spending and who is cashing the cheques.

Britain’s defence budget is set to reach £62.2 billion in 2025/26, rising to £73.5 billion by 2028/29. The government has committed to increasing spending to 2.6% of GDP by 2027, with a longer-term target of 3.5% by 2035, in line with the new NATO agreement that all 32 member states will spend 5% of GDP on security and defence. The Office for Budget Responsibility has calculated that reaching the 3.5% target alone would cost an additional £32 billion per year in today’s money.

To put that in perspective, Britain was already spending at Cold War highs in real terms before the latest increases were announced. RUSI analysis showed that with a defence budget of £56.9 billion, the UK had already matched the high point of late Cold War spending in 1984/85.

Who benefits from this escalation? BAE Systems, Britain’s largest arms manufacturer, reported record profits of more than £3 billion for 2024, a 14% increase in revenue, and an order backlog that reached £66.2 billion. The company expects sales to rise a further 7 to 9% in 2025. Its major shareholders include BlackRock, Capital Group, and Invesco.

BAE’s chief executive has publicly forecast “high-single-digit growth” for the foreseeable future, noting that heightened defence budgets are converting into “real financial performance.” Morgan Stanley projects that global defence spending could reach $2.1 trillion by 2027.

This is not conspiracy. It is commerce. The defence industry does not create threats, but it has an enormous financial interest in ensuring that threats are perceived as permanent and escalating. When the Prime Minister stands in Munich and declares that the age demands hard power, he is not speaking into a vacuum. He is speaking to an audience whose livelihoods depend on that sentence being believed.

What Gets Cut While the Guns Get Polished

The arithmetic of Starmer’s war economy is brutally simple, and it falls heaviest on those who can least afford it.

To fund the defence increase, the government slashed Britain’s foreign aid budget from 0.5% of gross national income to 0.3% by 2027. This represents approximately a 40% cut in current prices, reducing aid to its lowest level since 1999. The savings, estimated at £6.5 billion per year by 2027/28, are being transferred directly to the Ministry of Defence. The International Development Minister, Anneliese Dodds, resigned over the decision, warning that the cuts would “likely lead to a UK pull out from numerous African, Caribbean and Western Balkan nations.” Total aid to Africa will fall by £184 million. Funding for Sudan, Syria, and Yemen has already been savaged.

Let that settle. Britain is withdrawing aid from Sudan, where a civil war has created the world’s largest displacement crisis, in order to build warships to hunt Russian submarines that pose no direct threat to British territory.

Meanwhile, at home, the National Health Service continues its descent into managed dysfunction. The waiting list for hospital treatment in England stands at approximately 7.3 million cases, representing more than 6 million individual patients. The 18-week treatment target has not been met nationally since February 2016. In the most recent data, only around 61% of patients were seen within the constitutional standard. Nearly 192,000 patients have been waiting more than a year for care. Cancer diagnosis targets are being missed. A&E performance remains dismal. The Integrated Care System deficit for 2025/26 opened at £6.6 billion.

And the spending squeeze is tightening. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has warned that the defence increase is already squeezing budgets for other departments. Non-defence departmental spending is projected to be “almost flat” between 2026/27 and 2027/28, meaning that in real terms, after accounting for population growth and inflation, public services outside the military will be cut. The Chancellor did not raise taxes to fund the defence uplift. She raided the aid budget and imposed austerity by another name.

This is the real cost of Starmer’s war economy. Not soldiers in trenches, but patients in corridors. Not shells on a frontline, but aid workers withdrawing from famine zones. Not the defence of Britain, but the degradation of everything that makes Britain worth defending.

Sovereignty: The Word That Means Its Opposite

Perhaps the most striking feature of Starmer’s Munich speech is its treatment of sovereignty. He invoked the word repeatedly, insisting that Britain would “take control” by deepening its integration with European defence structures. He announced closer alignment with the EU single market, joint defence procurement, enhanced nuclear cooperation with France, a shared industrial base across the continent, and a commitment to “a more European NATO.”

He described Brexit as a period when Britain was “a burden” and declared that “there is no British security without Europe.”

You may agree or disagree with closer European integration. But it is worth noting the sleight of hand. Starmer is using the language of sovereignty to advance a programme that systematically reduces sovereign decision-making. Joint defence procurement means shared control over what weapons are built and where. A European defence industrial base means supply chains answerable to supranational authorities, not the House of Commons. Closer single market alignment means regulatory convergence without representation. None of this was in Labour’s manifesto. None of it was put to the electorate.

And it was telling that Starmer directed his most pointed remarks not at Russia, but at domestic political opponents. He attacked Reform UK and the Green Party by name, warning that their supporters risked enabling war. This is a Prime Minister with an approval rating that has cratered to historic lows, using a foreign stage to delegitimise domestic dissent. The message to the British voter was unmistakable: question the war footing and you are an extremist. Object to the spending priorities and you are soft on Russia. Demand accountability and you are undermining national security.

This is not leadership. It is management of consent through manufactured fear.

The Question That Must Be Asked

Strip away the rhetoric, and the core of Starmer’s position reduces to a syllogism. Russia is dangerous. Danger requires armament. Therefore, Britain must arm on a generational scale, cut aid to the world’s poorest, accept the continued degradation of public services, and deepen its integration with European military structures, all without meaningful public debate or democratic mandate.

Each link in that chain deserves scrutiny.

Russia is a diminished power fighting a war it cannot win decisively, with an economy smaller than Italy’s, a military that cannot conduct effective joint operations, and a demographic crisis that its own officials acknowledge. Nuclear deterrence, the very mechanism that has prevented great power conflict for seven decades, remains intact and is being strengthened. The hybrid threats Russia poses are real but are qualitatively different from the existential military danger invoked to justify generational rearmament.

The beneficiaries of permanent threat inflation are not working communities in Wigan or Hartlepool. They are defence contractors recording record profits, transatlantic security institutions seeking renewed relevance, and politicians who find it easier to invoke Churchill than to fix the NHS.

None of this means defence spending should be frozen, or that NATO is without value, or that Russia’s hybrid activities should be ignored. Reasonable people can disagree about the appropriate level of military preparedness. But reasonable people deserve an honest argument, not a manufactured atmosphere of emergency designed to foreclose debate.

If Britain is truly to be placed on a permanent war footing, if the public is to accept higher defence spending, reduced aid, squeezed public services, and diminished democratic oversight of military commitments, then the case must be made honestly and in full. The threat must be stated precisely, not inflated for political effect. The costs must be acknowledged, not hidden behind bureaucratic euphemism. The alternatives, diplomatic, economic, institutional, must be explored, not dismissed as appeasement.

Keir Starmer offered none of this in Munich. He offered instead a performance of seriousness: grave language, historical allusion, and the unmistakable implication that dissent is danger. It was a speech designed not to inform the public but to condition them. Not to defend Britain but to position its Prime Minister as a wartime leader, in a war that exists primarily in the minds of those who profit from its possibility.

The people of this country are not fools. They can distinguish between genuine security and manufactured emergency. They know that a nation which cannot treat its sick, house its young, or keep its promises to the world’s poorest is not made stronger by spending ever more on weapons to counter a threat that its own military leaders describe as manageable.

If the lamps are going out anywhere, they are going out in NHS waiting rooms, in defunded community services, in the aid programmes that once gave Britain moral authority. Starmer would do well to notice where the darkness is actually falling, before lecturing the rest of us about the light.

Because the real threat to Britain is not a Russian tank column that cannot reach Kyiv. The real threat is a political class that has learned to weaponise fear, and a public that has not yet learned to see through it.

Nations that forge ploughshares into swords can always reverse the process. Nations that build their economies on swords must find someone to swing them at…

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands