How Modern Power Rules with a Smile, And the Boot.

Power, wherever it lives, has a habit of calling itself moral. Whether it wears a flag, a crown, or a constitution, it insists that it protects rather than rules. That is why the idea of benevolent fascism is so dangerous, because it feels virtuous while it consolidates control. The uniforms may be neat, the rhetoric clean, the purpose declared noble, but underneath lies the same arrangement of authority over consent. What was once imposed by bayonet is now justified by security briefings and procedural language.

The courts become the new army. They entrench morality through verdicts, and the people grow accustomed to mistaking legality for justice. In both America, Britain and, in truth, across much of the so-called liberal world, law has replaced conscience as the instrument of order. Governments act, and when questioned, they answer not with ethics but with statutes. “It’s within the law,” they say, as if legality and legitimacy were the same thing.

But the lesson of the twentieth century should have cured us of that illusion. Everything the German government did between 1933 and 1945 was legal: authorised, debated, notarised, filed, and stamped. The concentration camp had paperwork. The deportation order had a signature. The theft of citizenship had a parliamentary majority. Law was the glove that hid the hand. When you remind a government of that, people rush to deny likeness. They say, we’re not them, and of course, they’re right. No one is claiming they are. But that isn’t the point. The point is that legality is not the same as virtue, and a state that forgets the difference has already begun to blur the boundary that protects conscience from compliance. Law is meant to follow morality, not replace it.

Benevolent fascism doesn’t shout; it smiles. It thanks you for your cooperation. It tells you that discipline is freedom and unity is peace. And people, tired of noise and fear, often accept the bargain. The tragedy of modern democracy is that it teaches us to vote for calm rather than choice. The result is a system that still calls itself free while it quietly removes the means of refusing.

There will be no curiosity, no enjoyment of the process of life. All competing pleasures will be destroyed. But always— do not forget this, Winston— always there will be the intoxication of power, constantly increasing and constantly growing subtler. Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless.

― George Orwell, 1984

If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face… forever.

Nowhere is that tension more visible than in the United States the country that most proudly calls itself the model of self-government. Its architecture of self-discovery, what it names federalism, was meant to balance liberty with order. Yet over time, that same architecture has hardened into permanence. What began as a covenant of equals has become a hierarchy of obedience. Federalism that cannot dissolve is only hierarchy by another name. True federation implies the right of exit; one that forbids it becomes a union of tenants who may never sell their house. The law that binds them is older than any living citizen and stronger than any present consent. Stability becomes a form of motionless power. A democracy that forbids its members to leave is a democracy afraid of itself.

People defend these systems as the best available form because they let them choose their managers. But choice without consequence isn’t democracy; it’s rotation. Senators, judges, presidents, each anchored for life or for decades, become stewards of permanence. Power that never risks extinction stops remembering who lent it legitimacy in the first place.

Reimagining Democracy: A Council of Equals, Not Career Politicians

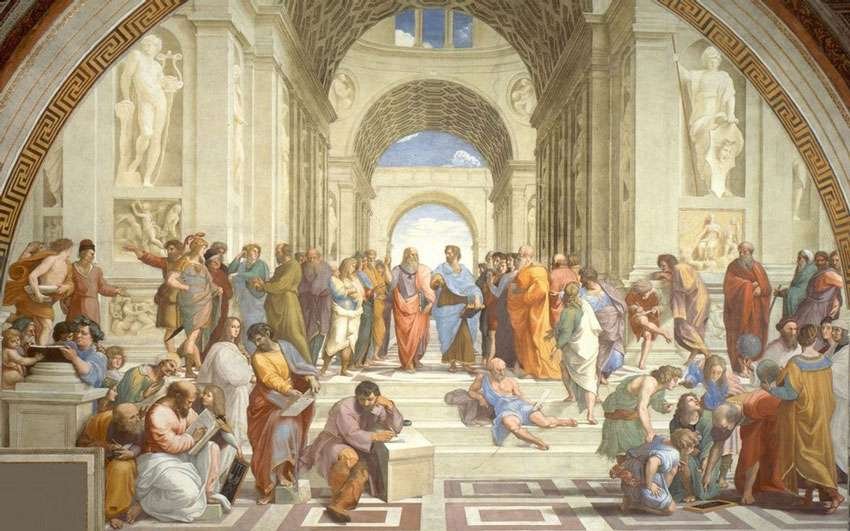

So imagine something else. Suppose every state were equal, not by population or wealth but by right of voice. A governor chosen by the people to run their home affairs, and a vice-governor sent to the national chamber as the living delegate of that will. One state, one seat, one vote. No second house, no professional legislature, just a council of equals arguing the nation’s direction. It would be the nearest thing a large democracy could build to the Athenian amphitheatre, the crowd distilled into a single debating circle. Not every citizen could stand there, but every citizen would know exactly who spoke for them and could recall them when they failed to.

Citizenship in Athens was a privilege of the few, men of pure descent, owners of bodies and of others. A modern democracy worthy of the name would not be. The ancient idea was participation; the modern correction is inclusion. Every voice, every household, every belief becomes part of the argument. The system’s beauty would be its impermanence: governors and delegates limited to two terms, presidents permitted no more than two non-consecutive terms in a lifetime. Power as rotation, not career. Leadership as a civic loan, not a profession. When a term ends, its holder returns to ordinary life, carrying the memory of authority back into the crowd where it belongs. The next person steps up, and the machine keeps breathing.

The presidency would exist because the world beyond still demands a single handshake, a single face for treaties and wars. But it would not be a throne. The delegates would choose the president from among the citizenry, not from themselves, ensuring no house becomes the nursery of kings. President and deputy from different states, serving once, perhaps twice, then gone. Enough to give continuity, never enough to grow roots, a system built on the idea that if a person cannot let go of power, they were unfit to hold it.

Critics will ask who I am to suggest such designs, especially of a country that isn’t mine. The answer is simple: I’m not telling anyone how to live. I’m asking how people might live, how democratic societies could organise themselves differently if they were drawn again from first principles. This isn’t a blueprint for one nation; it’s a meditation on possibility. The United States, with all its contradictions, offers a useful framework because it calls itself the world’s oldest modern democracy. The point isn’t to correct America. It’s to ask whether any society, anywhere, can still imagine itself anew.

Democracy was never meant to be a machine that runs on its own. It was supposed to be a habit of self-questioning, a willingness to redraw the map when the borders of fairness shift. The Athenians, for all their exclusions, understood that citizenship was participation, not worship. They climbed the steps to the amphitheatre and argued because silence was servitude. Maybe we can’t fit a whole nation into an amphitheatre anymore, but we can still keep the spirit of it alive, the noise, the disagreement, the refusal to let any single voice speak for too long.

That’s all this is: an act of imagination, not instruction, a sketch of what could be, drawn against the shadow of what is.

Guest post by Gary Lyon…

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands