The Moot: England’s Lost Democracy of People, Power, and Oak Trees

🎧 AI Audio Trial: Before Parliament, Before Kings, There Was the Moot (MP3)

It all began with a photograph my wife sent me on a Tuesday afternoon…

I was sitting at my desk, drowning in the usual depressing news cycle, when her message pinged through. “Look at this,” she wrote. “Thought you’d like it.” The image post from that showed a spiral staircase, but not just any staircase. This was a perfect coil of medieval brickwork winding upward like something out of an illuminated manuscript, each step worn smooth by centuries of feet climbing, a feast to the eye and imagination.

“Where is this?” I asked.

“Moot Hall, Maldon. Essex.”

Moot. The word caught in my mind like a burr. I knew it, of course, the way you know words you’ve heard all your life without ever really thinking about them. “A moot point”. Something debatable, something academic, something that doesn’t really matter anymore. But as I stared at that photograph, at that beautiful spiral disappearing into shadow, I realised I’d never actually asked myself what a ‘moot’ was. Or more importantly, what it had been.

So I did what any curious person does. I started digging. And what I found wasn’t just the history of a building. It was the history of an idea. An idea that’s been buried, suppressed, and nearly forgotten, but never quite destroyed. An idea about who has the right to rule, and who gets to decide. An idea that might be the most dangerous thing the powerful have ever tried to hide from us.

The image was a small stroke of serendipity, syncing perfectly with my own algorithm of history and democracy, as if the past itself were rebelling against its erasure. It offered a brief reprieve, pulling me away from the grim theatre of geopolitics and back into the imagination of what was, and what could be…

The People’s House of Maldon: Moot Hall

In the heart of Maldon stands Moot Hall, a Grade I listed building that has watched over the town for more than six centuries. Built around 1420, this remarkable red-brick structure, famous for that elegant spiral staircase twisting through its tower, is one of England’s oldest surviving civic buildings. Tourists photograph it. Heritage groups preserve it. Local councils hold events in it.

But Moot Hall is far more than an architectural treasure or a pretty backdrop for wedding photos. It is a living symbol of an idea that predates monarchy, empire, and Parliament itself: the ancient right of ordinary people to govern their own affairs.

The word moot comes from the Old English mōt or gemōt, meaning a meeting or assembly. Long before Westminster, and long before kings ruled by divine decree, the people of the Anglo-Saxon shires and hundreds met in moots. These were open assemblies of freemen and women who gathered to settle disputes, uphold custom, and make collective decisions. These gatherings were not the privilege of the elite but the duty of the community. Every landholder, every head of household, every able-bodied person could speak. Justice was local, transparent, and rooted in consensus.

This was democracy before we had a word for it. Before political theory. Before constitutions. Just people, gathering under an oak tree or on a hillside, deciding together how they would live.

The Anglo-Saxon Moot: Where Law and Community Met

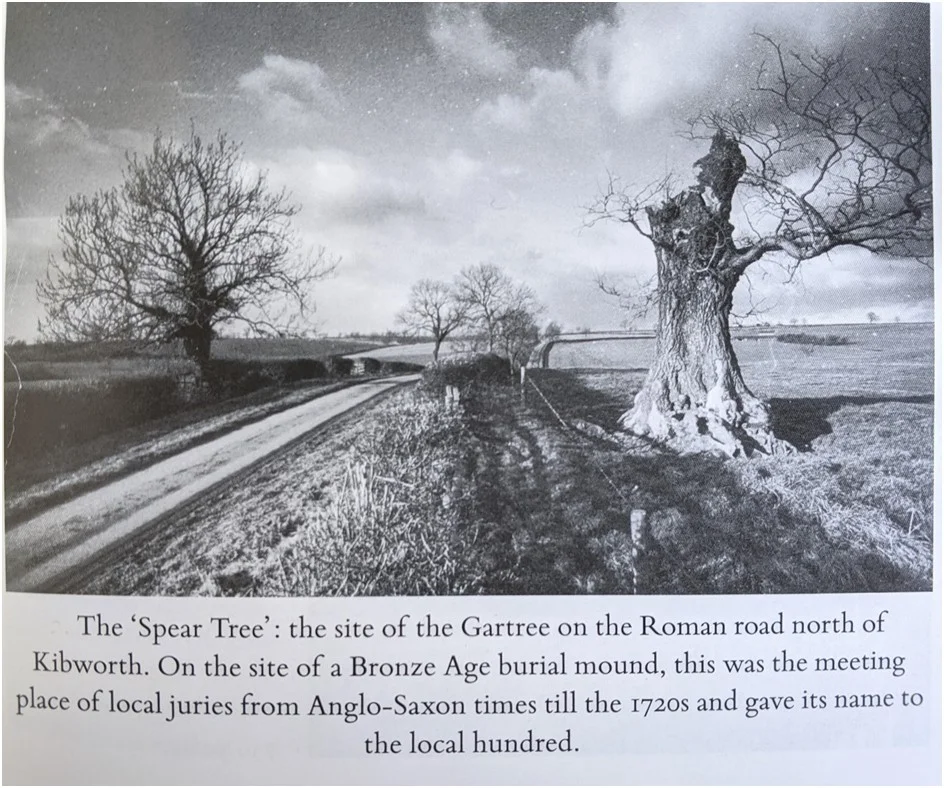

The moots were more than courts. They were the heartbeat of local democracy. Across early medieval England, every shire held its own shire moot, attended by local lords and bishops, the sheriff, and four delegates from each village. Below them were the hundred moots, smaller regional assemblies named after the hundred households they represented. And below that, at the most local level, were village moots where neighbours settled everyday disputes.

These moots dealt with everything. Boundary disputes and taxation. Criminal cases and military obligations. Inheritance rights and marriage contracts. The decisions made were based on customary law, passed down through generations, rather than royal edict. They were, in essence, the people’s parliaments, rooted in oral tradition, mutual accountability, and a shared sense of justice.

But the moots were social as well as political. They were gatherings that strengthened bonds of community and reinforced the unwritten rules that kept society stable. The act of meeting, speaking, and listening to one another under the “moot tree” or on the “moot hill” was itself a declaration of belonging and shared responsibility. It was democracy in its rawest form: neighbours judging neighbours, not strangers ruling from afar.

And here’s what matters most. Even the Anglo-Saxon kings were not absolute. They were chosen, sometimes elected, by the Witenagemot, the council of the wise, and could be deposed if they failed in their duty. Power flowed upward from the common folk, not downward from the crown. Authority, in that old English sense, was conditional on service to the people.

Read that again. The king served the people. Not the other way around. The people chose their rulers and could unmake them when they betrayed that trust. This wasn’t theory. This was how England actually worked for centuries before 1066.

The Norman Yoke and the Long Shadow of Conquest

When Moot Hall was built in the 15th century, England had long since lost that native democracy. The Norman invasion of 1066 crushed the Anglo-Saxon commons beneath the weight of feudal hierarchy. William the Conqueror and his French-speaking barons didn’t just take the throne. They took everything. The land. The law. The language. The very idea that ordinary people had any say in how they were governed.

What had been a culture of open assembly became a system of command. The oak trees where free men once gathered were replaced by stone castles and manorial courts. The people who had chosen their kings were reduced to subjects, then to serfs. The Norman sword conquered the land, but it could not quite extinguish the old idea of government by consent. That idea went underground, preserved in folk memory, in local custom, in the stubborn insistence of English common law that some things were beyond the king’s power to change.

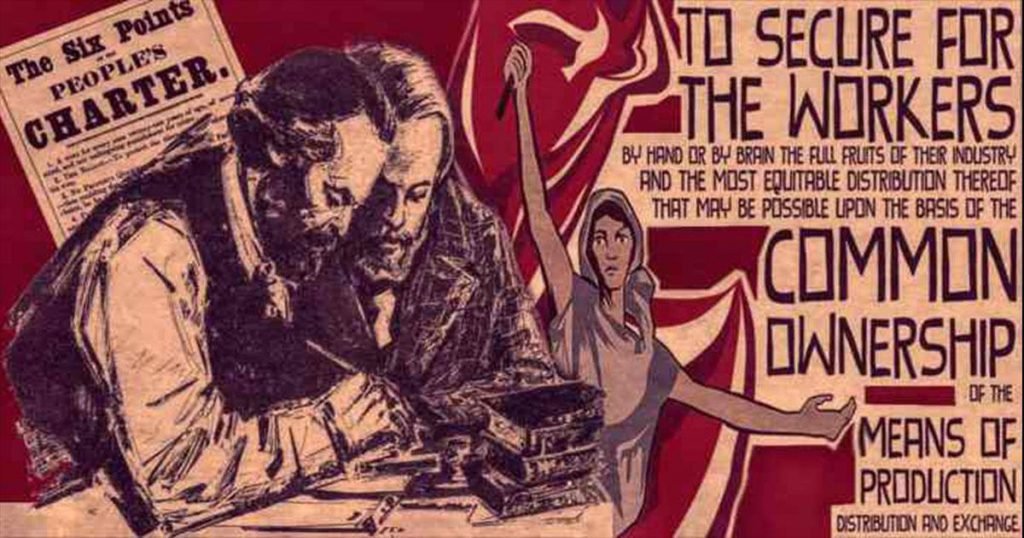

Centuries later, that spirit resurfaced. When the Diggers rose during the English Revolution in 1649, they spoke of “removing the Norman yoke.” Five hundred years after Hastings, the language of the Anglo-Saxon commons still burned in their words. They remembered that freedom in England was not granted from above; it was claimed from below. The Levellers, who argued that government derived its power from the consent of the governed, were reaching back to pre-Norman ideas of popular sovereignty.

Moot Hall stands as a witness to that lineage. From the moots beneath the trees, to the Diggers on St George’s Hill, to the Levellers demanding votes for every man, to the Chartists, to the suffragettes, to the Clay Cross councillors who defied Westminster for their constituents. Every working-class movement that has ever dared to say “this land is ours” is echoing the voice of those Anglo-Saxon assemblies.

Moot Hall: A Survivor of the People’s Tradition

Moot Hall, rising in 1420, centuries after the conquest, is a remnant of that older spirit. A brick-and-mortar echo of England’s first experiments in self-rule. For generations it served as courthouse, council chamber, and town meeting place, carrying forward the thread of civic independence the Normans could never quite erase.

Think about what it meant for a town to build such a place. This wasn’t a lord’s manor or a royal palace. This was the people’s house. A space where the community could gather, debate, and decide. Where justice was administered not by distant authority but by local people applying local custom. Where the voice of the merchant and the craftsman and the farmer carried weight.

Its famous spiral staircase, winding from ground floor to rooftop, is more than a feat of craftsmanship. It is a metaphor. The people’s long climb from subjugation back toward self-governance. Each step worn smooth by the feet of those who came to seek justice, to give testimony, to participate in the governance of their community. Each turn of the spiral a reminder that democracy, like history itself, moves in circles rather than straight lines. We climb, we fall back, we climb again.

The Moot’s Legacy in English Law

Traces of the old moots remain embedded in the English common-law system. Our reliance on precedent, the idea that justice must be consistent with previous judgments, stems from the moots’ respect for custom and communal memory. So too does our tradition of open courts and public deliberation. The jury system itself is a descendant of the moot’s collective judgment.

The hundred and shire moots evolved into county courts and, eventually, into the parliamentary system itself. Yet something vital was lost in that evolution: the intimacy of representation. The moot was not a distant legislature; it was a gathering of neighbours. Everyone present could see the faces of those who spoke for them. You couldn’t hide behind party whips or carefully worded press releases. You stood there, in front of your community, and answered for your decisions.

Perhaps that is why Moot Hall still matters. It reminds us that democracy was once personal, physical, and participatory. It was not about online petitions or five-year electoral cycles or professional politicians who parachute into safe seats. It was about standing in a room with your community and deciding your own fate.

Bringing Back the Moot

Maybe it is time to bring the moot back. Not as historical re-enactment or tourist attraction, but as living practice. Imagine if our Members of Parliament were required to meet monthly with their constituents in open assemblies. Not stage-managed town halls with pre-screened questions. Real gatherings where any constituent could speak, challenge, demand answers. Where MPs had to face the people directly, explain their votes, account for their actions.

Imagine if local councils couldn’t make decisions about housing or planning or public services without holding genuine public moots where residents had real power to shape outcomes. Not consultation exercises designed to rubber-stamp predetermined decisions, but actual democratic assemblies where the community decides.

We are ruled today by committees, quangos, think tanks, and corporate lobbyists. Decisions that affect our lives are made by people we never see, in rooms we can’t enter, using criteria we don’t understand. Politics has become a spectator sport where we’re allowed to choose between pre-packaged options every few years, then told to shut up and trust the experts in between.

The moots remind us that government should not be an abstraction. It should be a conversation. Democracy should not be a show we watch; it should be work we do.

The Lesson of Moot Hall

To look inside Moot Hall is to feel the continuity of that struggle, the centuries-long fight between the few who claim the right to rule and the many who demand the right to be heard. The Anglo-Saxon moots once chose their kings and could unmake them when they betrayed their trust. That was the foundation of our democratic instinct: rulers are servants, not masters. Power flows upward, not downward.

That principle terrifies those in power. Always has. Because if people truly believed it, if they acted on it, the whole edifice of top-down authority would crumble. So they bury the history. They turn moot into an academic word meaning “irrelevant.” They teach us that democracy began with Magna Carta (a deal between barons and a king) or the Glorious Revolution (which replaced one elite with another) or the gradual extension of the franchise (granted grudgingly after centuries of struggle). They don’t teach us about the moots. They don’t tell us that ordinary English people once governed themselves.

Perhaps that is the lesson of Moot Hall today. If we wish to reclaim democracy from those who wield it as a slogan while hoarding power, we must go back to its roots. We must once again meet, debate, and decide together. Politics must return to the people, to the moot, or it will cease to be democracy at all.

As the 12th-century chronicler William of Malmesbury wrote of the old English kings, “They ruled by the will of the people, not by terror of the sword.” That principle, born in the moots and shires of early England, still waits to be reclaimed.

Climbing the Staircase

When I look again at that photograph my wife sent me, I see more than medieval brickwork. I see the turning of history itself. A path that rises, falters, and rises again. Every generation must climb those steps anew, reclaiming what was taken, rebuilding what was lost.

The Anglo-Saxons met beneath trees. The Diggers sowed hope on common ground. The Levellers spoke of liberty. The Chartists demanded the vote. The Clay Cross councillors defied Westminster for their people. And still the same question echoes through the centuries: who rules, and in whose name?

Perhaps that old staircase at Maldon leads us not just upward through stone and time, but back to something deeper. The understanding that democracy was never a gift from above. It was, and remains, something built from the ground up by ordinary people who refuse to be ruled without their consent.

The powerful have spent nearly a thousand years trying to make us forget this. They’ve succeeded so well that we now think democracy means voting every few years and hoping for the best. But Moot Hall remembers. Those worn steps remember. The spiral keeps turning, and if we’re willing to climb it, we might just find our way back to what we lost in 1066.

By Paul Knaggs

Labour Heartlands Editorial Feature

There’s a reminder somewhere in all this… “Power once belonged to the people, and more so, can be taken back by them at any time.”

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands