The Corporate Capitulation: Starmer Folds to Silicon Valley

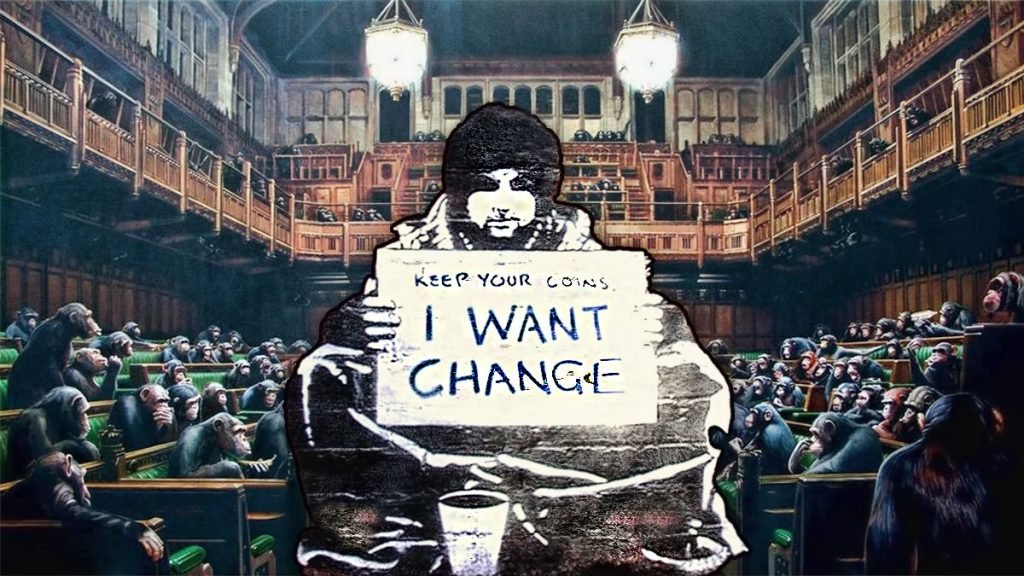

Another U-turn. Another betrayal. Another reminder that for all Labour’s rhetoric about change, when corporate power flexes its muscles, Starmer folds like a cheap suit.

The British government is preparing to roll back its pledge to make Big Tech companies pay for the tsunami of fraud originating on their platforms. According to sources with direct knowledge of the upcoming fraud strategy, there will be no financial incentive, no meaningful consequences, no tangible cost for social media giants like Meta or telecommunications firms like Virgin Media to crack down on the scams that are bleeding British victims dry.

This matters. Not just because fraud now constitutes 44 percent of all crime in the United Kingdom. Not just because 70 percent of fraudulent payments start on an online platform. Not just because more than half of payment scams in Britain involve a Meta platform, with users defrauded of £62.7 million via Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp in 2023 alone. But because Keir Starmer explicitly, unambiguously, repeatedly promised to fix this before the election.

During the campaign, when Labour was still pretending to challenge power rather than serve it, Starmer told a pre-election debate that tech companies should have a “clear obligation and a clear financial incentive” to prevent scams. He was even more direct in a written statement: “At the moment, Britain’s banks do most of the work of trying to prevent and detect fraudulent transactions, and bear all the cost of reimbursing victims, but the tech giants do little or nothing for either effort. That has to change.”

That has to change. Four words that sounded like a promise. That felt like accountability. That suggested Labour might actually stand up to corporate power when it mattered.

Except it didn’t change. And it won’t change. Because between July’s election victory and now, something happened. Or rather, someone happened. Donald Trump won the American presidency, and suddenly the Labour government discovered that taking on American tech companies might have consequences for the “special relationship.”

Trump threatened “substantial” additional tariffs on countries imposing digital services taxes on American companies, calling such taxes “discriminatory.” And just like that, Labour’s courage evaporated. The writing appeared on the wall in July when Chancellor Rachel Reeves, Home Secretary Yvette Cooper, and Technology Secretary Peter Kyle wrote to Big Tech firms not demanding action but praising their “demonstrable” efforts on combating fraud.

Praising them. For doing nothing whilst billions are stolen from British citizens on their platforms. For profiting from the attention economy that makes fraud not just possible but profitable. For creating the infrastructure that enables scammers whilst bearing none of the cost when victims need reimbursing.

Currently, banks must reimburse victims of payment scams up to £85,000. Think about that regulatory framework for a moment. A scammer uses Facebook to contact a victim. Uses WhatsApp to gain their trust. Uses sophisticated social engineering techniques perfected on these platforms to manipulate them into authorising a payment. The fraud succeeds because Meta’s verification systems are non-existent and their response to reported scams is glacial. But when the victim needs compensation, who pays? Not Meta, despite providing the infrastructure. Not the telecommunications company that carried the fraudulent messages. The bank. The institution that had the least involvement in enabling the fraud pays the entire cost.

This isn’t justice. This is a business model. Tech platforms profit from user engagement, including engagement with scammers, whilst externalising all the costs onto the financial sector. It’s the same logic that lets corporations pollute whilst taxpayers fund the cleanup. The same principle that allows Amazon to destroy high streets whilst local councils pick up the social costs. Privatise the profits, socialise the losses. It’s capitalism in its purest form, and Labour was elected promising to challenge it.

UK Finance, the bank lobby group, has been screaming about this for years. In August, they wrote to Fraud Minister David Hanson pointing out that no improvement had been made by the platforms and “the financial services sector continues to shoulder the burden of reimbursing victims, with no tangible alignment with and from those sectors where fraud originates.”

But here’s where it gets interesting. Because this isn’t a case of banks being noble victims. This is a case of one corporate sector asking government to make another corporate sector share the costs. And the government, faced with choosing between British banks and American tech giants, has chosen the latter. Not because it’s right. Not because it serves British people. But because American tech companies wield more power than British banks, and because Trump’s threats carry more weight than electoral promises.

The upcoming fraud strategy, still in draft but unlikely to change substantially before publication early next year, contains no financial penalties for tech companies. No mandatory reimbursement schemes. No skin in the game whatsoever. It includes a data sharing agreement between banks and law enforcement, which the financial services industry supports but which does nothing to address the fundamental problem: platforms that enable fraud whilst bearing no responsibility for it.

Most damningly, the strategy contains no specific targets for reducing fraud. Just a vague aspiration to bring it down. As one financial services executive observed, this means “no accountability.” If fraud drops by 0.1 percent, will that be declared a success? “This feels like a document written by people with no ambition or money to solve the fraud problem,” they said.

More likely, it’s a document written by people who had ambition until they encountered power, then discovered that promises made to voters matter less than relationships with Silicon Valley.

This is the pattern with Starmer’s government. Bold promises in opposition. Timid retreat in power. Whether it’s the Trilateral Commission membership that shapes his worldview, the corporate donations that fund his party, or simply the grinding reality that challenging powerful interests requires courage Labour no longer possesses, the result is the same. When it matters, when real interests clash, when standing up to power might actually cost something, Starmer folds.

Think about the priorities this reveals. Fraud constitutes 44 percent of all crime in Britain. Nearly half of all criminal activity. Overwhelmingly targeting vulnerable people, pensioners, those who trust too easily or understand technology too little. Causing not just financial loss but psychological trauma, destroying victims’ faith in humanity alongside their bank balances. And the platforms where most of this fraud originates face no consequences whatsoever for their role in enabling it.

Meanwhile, if you fail to pay your TV licence or your council tax, the state will come for you with terrifying efficiency. Miss a benefits appointment and you face sanctions. But if you’re Meta, facilitating billions in fraud whilst generating obscene profits, the British government writes you thank-you notes for your “demonstrable efforts.”

The Home Office response to these revelations is a masterpiece of meaningless bureaucratic language: “Fraud is a serious and damaging crime, and we are determined to bring those responsible to justice. That’s why we’re developing an ambitious Fraud Strategy, which places working collaboratively with a range of partners, which we will be publishing in the new year. We continue to urge tech companies to step up to go further and faster to protect the public on their platforms.”

Urge. That’s the operative word. Not require. Not mandate. Not make financially liable. Urge. As if Meta’s board of directors will be moved by strongly worded letters from British ministers. As if collaboration and partnership and urging have any effect on corporations whose only obligation is to shareholders and whose only imperative is profit.

This is what happens when a supposedly left-wing government encounters real power. Not the imagined power of unions or activists or the people who actually elected them. But the actual power of trillion-dollar corporations that can threaten market access, lobby relentlessly, fund opposition campaigns, and ultimately remind any government that in the modern global economy, capital is mobile and politicians are not.

Banks are furious about this U-turn, and whilst their fury comes from self-interest rather than principle, they’re not wrong. They’re being asked to bear the entire cost of a problem they didn’t create, on platforms they don’t control, because the government lacks the courage to make those platforms share responsibility.

But the real victims aren’t banks. They’re the people who will continue to be scammed, who will continue to lose their savings to fraudsters operating on platforms that face no meaningful consequences for enabling them. They’re the vulnerable and the elderly and the trusting who believed their government when it promised to make tech companies accountable.

Starmer U-turns. That’s nothing new. What’s new is how quickly the pretence has dropped. How little time elapsed between “tech companies must have clear financial incentives” and praising their “demonstrable efforts” whilst asking them nicely to do better. How thoroughly Labour has revealed itself as a party that will promise anything to get elected and abandon everything once power requires choosing between voters and corporate interests.

Fraud is 44 percent of British crime. Meta platforms facilitate over half of payment scams. But making them financially liable might upset Trump and threaten trade relationships and remind everyone that Britain is a declining power that cannot afford to challenge American tech giants no matter how much they fleece British citizens.

When your government is more afraid of Silicon Valley than it is accountable to voters, you don’t have a democracy. You have a corporate subsidiary where elections change the faces but never the policy, where promises last until power reveals their cost, and where the only question that matters is not what’s right but what powerful interests will tolerate.

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands