The 1966 Aberfan Disaster, one of Britain’s most tragic mining disasters, where a collapsing mountain of coal waste killed 116 school children.

The last sounds heard in Pantglas Junior School were children’s voices raised in excited chatter about the coming half-term holiday. No one heard the mountain move.

On that fog-shrouded Friday morning of October 21, 1966, mothers stood in doorways across Aberfan, watching their children navigate the rain-slicked streets of their Welsh mining village. As the children left the coal-fire warmth of home they emerged into streets shrouded with a dense, cold fog.

Mothers waved goodbye from the doorstep, never imagining in their worst nightmares that it would be for the last time. For 116 of those children, it would be the last goodbye.

The Morning Aberfan Lost Its Children…

The day began like countless others in this coal-dusted corner of Wales. Children traced their familiar paths through narrow lanes between terraced houses, past coal fires glowing in hearths, beneath the looming presence of Tip No. 7 – a man-made mountain of mining waste that had grown for decades on the hillside above their village. The waste heap was more than coal dust and rock; it was a monument to industrial indifference, a disaster waiting to happen that everyone could see but no one would stop.

On arriving at school, children congregated for morning assembly, they were excited.

At midday, the half-term holiday would begin.

Their daily rendition of ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ – a hymn written a few miles away in the bucolic tranquillity of the Usk Valley – was postponed that day.

They would sing it before they went home when the headteacher planned to wish her pupils a safe and enjoyable holiday.

The children filed into classrooms.

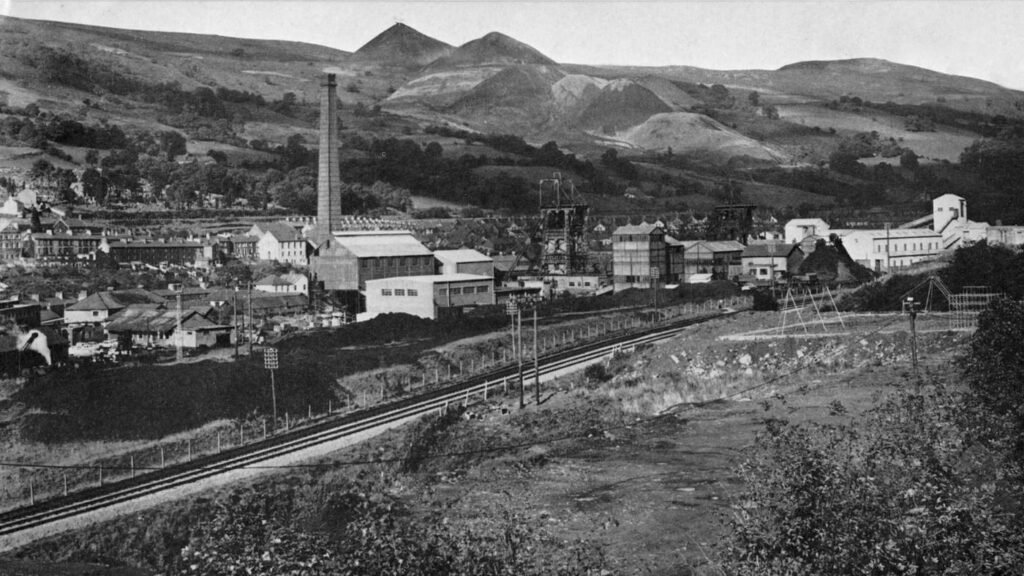

And so the world turned in Aberfan much as it had done for the past 100 years, when the community burgeoned around the Merthyr Vale colliery which began in 1869.

But then time stopped. At around quarter past nine on the morning of Friday 21 October 1966, disaster struck and all changed.

9:13 a.m., the mountain moved.

In less time than it takes to read this sentence, 300,000 cubic yards of liquefied coal waste broke free. The black tsunami gathered speed as it raced downhill, consuming everything in its path. It struck Pantglas Junior School with such force that the building’s walls exploded inward. Inside, children who moments before had been opening books and sharpening pencils found themselves buried alive beneath a horrific mixture of coal, shale, and mud.

What followed was a desperate race against time. Hundreds of miners – men who had spent their lives digging coal from beneath the Welsh earth – now clawed frantically at the slurry with bare hands, trying to reach the buried children. Some dug until their fingers bled. Others dug even as they knew they were searching for their own children.

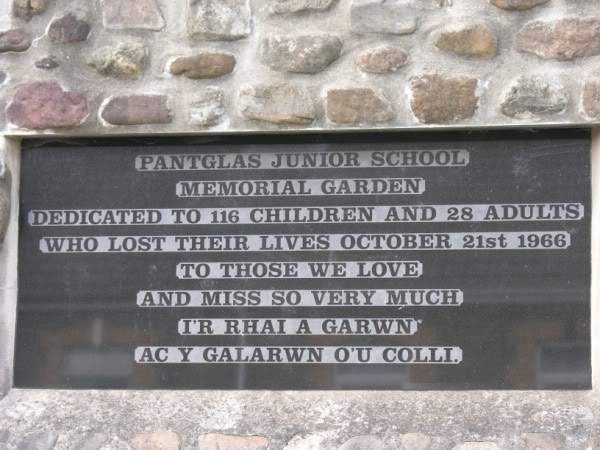

By day’s end, 144 people lay dead – 116 children and 28 adults. An entire generation of Aberfan’s children was gone, and with them, the village’s future. But this was no natural disaster. This was a human-made catastrophe, born of negligence and killed by indifference. The coal board had been warned. The residents had complained. Engineers had raised concerns. Yet the tips had continued to grow, fed by an industry that valued profit over lives.

The true tragedy of Aberfan lies not just in the lives lost that rainy October morning, but in the knowledge that every death was preventable. Every child who walked to school that day might have lived, had those in power simply listened, simply cared, simply acted.

“Our valley was going black, and the slag heap had grown so much it was half-way along to our house. Young I was and small I was, but young or small I knew it was wrong, and I said so to my father.”

How Green Was My Valley by Richard Llewellyn

If only…

At 07:30 that Friday the tip was reported to have sunk 20ft.

“If only fate had played its hand 20 minutes earlier, the school would have been empty.”

One tipping gang worker told a subsequent inquiry how the slide began.

“It was starting to come back up,” he said. “It started to rise slowly at first, sir… I thought I was seeing things. Then it rose up pretty fast, sir, at a tremendous speed.

“Then it sort of came up out of the depression and turned itself into a wave… down towards the mountain… towards Aberfan village… into the mist.”

Seconds later the bottom of the tip shot out.

Down in Pantglas Junior School, the lights began to flicker and sway; an ominous roar like “a jet plane screaming low over the school in the fog”.

The glistening black avalanche consumed rocks, trees, farm cottages then ruptured the Brecon Beacons to Cardiff water main, engorging it further and increasing the velocity of its murderous descent towards Pantglas.

Seconds after it hit, Cyril Vaughan, a teacher at the neighbouring senior school, said “Everything was so quiet”.

“As if nature had realised that a tremendous mistake had been made and nature was speechless.”

The top of the tip on the day of the slip. The alarm could not be raised by telephone as the cable had been stolen but it would have made no difference as the slide reached speeds of up to 50mph

The tips above the village

Every mining community had its tips. The entire South Wales Valleys landscape was jagged with them.

Big lump coal was required for domestic heating so the waste and tailings – fine particles left after the washing process – was loaded onto rail trams and dumped at the top of the valley, land of no economic value.

The tips were notorious for sliding but there was particular concern about Aberfan’s ‘tip number seven’ which had begun in 1958 and had risen to a 111ft (34m) heap of some 300,000 cubic yards (229,300 cubic metres) of waste.

It lay on highly porous sandstone riven with streams and underwater springs.

It had slipped three years previously when an ominous crater appeared at the top.

A bulge had formed at the foot of the tip as mountain spring water, unable to drain away, liquefied the spoil into thick, black quicksand.

The NCB brushed complaints aside.

The threat was implicit – make a fuss and the mine would close.

While many spoke out about the dangers, others who had misgivings held their tongue, recalling grim memories of long years of unemployment in the valleys.

There are thought to be about 20 or so of the surviving children left in Aberfan.

Some have moved away, some have sadly suffered early deaths; each of them has struggled to deal with the devastation wrought on their lives.

“Many of the people involved in the disaster find relationships very difficult,” says Jeff, who never married.

“Marriages have broken down because of the difficulties of living with someone who has gone through a major incident – the irrationality of your thoughts on occasions, your irritability and difficulty in confiding in people.”

There is no doubt in Jeff’s mind that a positive contribution to arise from the tragedy has been helping to improve psychological trauma understanding and help for other victims and their families.

Just as Dr Jones, who died in 2013, concluded: “Nowhere has grief been so concentrated. Lockerbie, Zeebrugge, King’s Cross – everywhere they used the lesson this place taught them.”

The search

After the landslide stopped, local residents rushed to the school and began digging through the rubble, moving material by hand or with garden tools.

A whistle would blow and the men would stop working; there would be an agonising silence as they strained to hear the faintest sound from underneath

At 9:25 am Merthyr Tydfil police received a phone call from a local resident who said “I have been asked to inform that there has been a landslide at Pantglas. The tip has come down on the school”; the fire brigade, based in Merthyr Tydfil, received a call at about the same time.

Yvonne Price, then 21, was one of the first police officers on the scene. She recalls being rigid with shock.

As her patrol car turned into the village, the driver screamed: “I can’t get through… The water’s rising… the water’s rising.

“A huge bank of water was coming directly towards us,” she says. “It was like a tsunami, it was terrifying.”

Calls were then made to local hospitals, the ambulance service and the local Civil Defence Corps. The first miners from the Aberfan colliery arrived within 20 minutes of the disaster, having been raised from the coal seams where they had been working.

They directed the early digging, knowing that unplanned excavation could lead to collapse of the spoil and the remnants of the buildings; they worked in organised groups under the control of their pit managers.

News reports described the site as resembling an earthquake or the aftermath of a high-explosive bomb

The first casualties from the wreckage of the school arrived at St Tydfil’s Hospital in Merthyr Tydfil at 9:50 am; the remaining rescued casualties all arrived before 11:00 am: 22 children, one of whom was dead on arrival, and 5 adults. A further 9 casualties were sent to the East Glamorgan General Hospital.

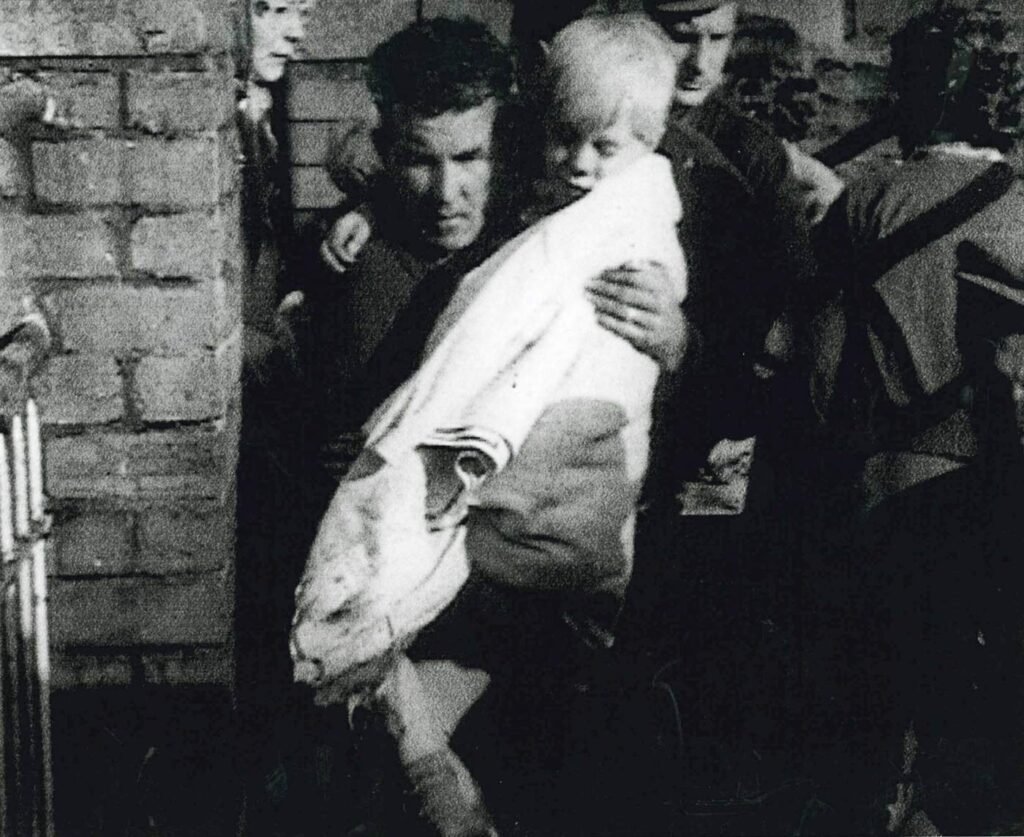

Jeff Edwards was eight years old at the time of the disaster. He was pulled out of the rubble (pictured) after rescuers noticed his distinctive white hair. He went on to be an accountant and leader of Merthyr Tydfil council.

We were looking forward to half-term, because the holidays started that afternoon.

I walked from our house on Aberfan Road about three doors down where I picked up Robert Jones, the local GP’s son and my best friend.

We used to walk through the gullies and stop at a little shop for some sweets, things like ‘shrimps and flying saucers’.

It was a Friday so it was library book day. I’d finished the Janet and John reading scheme. Once you finished that series of books, you could go on to library books, kept on a shelf at the opposite side of the class from where I was sitting. So from those books, I picked Herge’s Adventures of Tintin and I walked back to my desk.

We put our books away then and the teacher started the first lesson, which I think was maths. As he was teaching there was this sort of rumbling sound and that progressively got louder and louder. And to reassure the class, he said ‘Don’t worry, it’s only thunder’. The lights that were suspended on long wires started to shake back and forth.

My right leg was stuck in a radiator and there was hot water coming out onto my leg.

Jeff Edwards

The next thing I remember was waking up with all this material around me. Obviously, I didn’t know what had happened, other than the fact I was trapped. I could hear screams and shouts but I couldn’t move because the desk was up against my stomach, all the material from the roof had collapsed on top of me and there was a dead girl to the left of me.

My right leg was stuck in a radiator and there was hot water coming out onto my leg.

Somebody said ‘Look, there’s somebody down here’. My hair was very white, I was very blonde. The fireman who rescued me used his hatchet and broke the desk up and he pulled the stuff away. I was then lifted out of where I was trapped, and I was thrown in a human chain from one fireman to another, and to other people who had come to rescue.

Jeff Edwards, who was eight years old at the time of the disaster

I was covered in a blanket and then carried out into Moy Road. By the time I got out, which was just after 11 o’clock, all the ambulances had gone. So I was taken to St Tydfil’s Hospital by Tom Harding, who was a fruiterer in the village.

I remember his van, which was a light blue Bedford van, parked in the lane just down from the school. He had difficulty in starting the van because I think the water that was coming down had got up his exhaust. They had to push the van to start it off.

I was shipped up then to St Tydfil’s Hospital and I had head injuries and stomach injuries. Those physical injuries would heal over time but I think it’s the psychological injuries that would be with us right up until today. We won’t get rid of them, we’ll have to live with them. I think that’s the difficulty dealing with post traumatic stress disorder. It’s a long-term thing.

I couldn’t then return to the village because I was so frightened of the tip coming down again so I stayed with my gran up in Pentrebach until I felt confident enough to come back.

We were reliving what happened to us in days, the weeks and the months after. I often had nightmares. That was something that our parents had to deal with because they’d never experienced that before. I was afraid of noise, I was afraid of crowds, I was afraid of going to school, and for many years I couldn’t go to school because I was afraid that something would happen to me.

The 10th and last child to be brought out alive, he was treated for head and stomach injuries.

One of Aberfan’s three local GPs, the late Dr Arthur Jones, spoke of a “strange bitterness between families who lost children and those who hadn’t; people just could not help it”.

“You have feelings of guilt that you survived, ‘why me?’,” Jeff says, keen to point out that some parents who lost children were extremely supportive of him.

“It is a very difficult emotion to come to terms with. We had no childhood, it was taken from us.

“Play is an important part of a child’s development but that stopped. Most of the kids we played with were gone and play was frowned upon by some parents who lost children.”

Survivor guilt was not the only burden.

The symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) began to show but in 1966 there was little understanding or recognition of the syndrome.

Determined the world would learn from the mistakes of Aberfan he has contributed to NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) guidelines on PTSD, taken part in clinical studies and spoken at conferences and personally helped victims of Enniskillen, Dunblane, Paddington and the 2011 tsunami in Japan.

“After the disaster, we had interventions from psychiatrists,” Jeff says.

“But services were in their infancy. They didn’t really know how to deal with it and it wasn’t much help. There were sessions and we were offered different drugs.”

Jeff says the surviving children did not really have a formal education for many years.

“We didn’t want to go to school as we were afraid it would happen again,” he says.

“The children who survived had to come to terms with the loss of their friends and the scenes of carnage they witnessed.”

Time and again, testimonies from the past describe the same thing – no one talked about what happened.

This was an age of stoicism, embodied by the tough, macho miners themselves. Psychological help was stigmatised and viewed with suspicion.

“I couldn’t speak about what happened to my parents because of the horrific things I saw, you felt you didn’t want to put them through that,” says Jeff, who has never spoken about it to his mother to this day.

No survivors were found after 11:00 am. Of the 144 people who died in the disaster, 116 were children, mostly between the ages of 7 and 10; 109 of the children died inside Pantglas Junior School. Five of the adults who died were teachers at the school. An additional 6 adults and 29 children were injured.

The 10:30 am BBC news summary led with the story of the accident. The result was that thousands of volunteers travelled to Aberfan to help, although their efforts often hampered the work of the experienced miners or trained rescue teams.

With the two broken water mains still pumping water into the spoil in Aberfan, the slip continued to move through the village, and it was not until 11:30 am that the water authorities managed to turn off the supply.

It was estimated that the mains added between 2 and 3 million imperial gallons (9–14 million litres) of water to the spoil slurry. With movement in the upper slopes still a danger, at 12:00 noon NCB engineers began digging a drainage channel, with the aim of stabilising the tip. It took two hours to reroute the water to a safer place, from where it was diverted into an existing water course.

Never in my life have I seen anything like this. I hope I shall never see anything like it again. For years of course the miners have been used to… disaster. Today for the first time in history the roll call was called in the street. It was the miners’ children.

– THE LATE CLIFF MICHELMORE’S FIRST TV REPORT FROM THE SCENE

An NCB board meeting that morning, headed by the organisation’s chairman, Lord Robens, was informed of the disaster. It was decided that the company’s Director-General of Production and its Chief Safety Engineer should inspect the situation, and they left for the village immediately.

In his autobiography, Robens stated that the decision for him not to go was because “the appearance of a layman at too early a stage inevitably distracts senior and essential people from the tasks upon which they should be exclusively concentrating”.

Instead of visiting the scene, that evening Robens went to the ceremony to invest him as the chancellor of the University of Surrey. NCB officers covered for him when contacted by Cledwyn Hughes, the Secretary of State for Wales, falsely claiming that Robens was personally directing relief work.

Hughes visited the scene at 4:00 pm for an hour. He telephoned Harold Wilson, the Prime Minister, and confirmed Wilson’s own thought that he should also visit.

Wilson told Hughes to “take whatever action he thought necessary, irrespective of any considerations of ‘normal procedures’, expenditure or statutory limitations”. Wilson arrived at Aberfan at 9.40 pm, where he heard reports from the police and civil defence forces, and visited the rescue workers. Before he left, at midnight, he and Hughes agreed that a high-level independent inquiry needed to be held.

A makeshift mortuary was set up in the village’s Bethania Chapel on 21 October and operated until 4 November, 250 yards (229 m) from the disaster site; members of the Glamorgan Constabulary force assisted with the identification and registration of the victims. Two doctors examined the bodies and issued death certificates; the cause of death was typically asphyxia, fractured skull or multiple crush injuries.

Cramped conditions in the chapel meant that parents could only be admitted one at a time to identify the bodies of their children.

The building also acted as a missing persons bureau and its vestry was used by Red Cross volunteers and St John Ambulance stretcher-bearers. Four hundred embalmers volunteered to assist with the cleaning and dressing of the corpses; a contingent that flew over from Northern Ireland removed the seats of their plane to transport child-sized coffins.

The smaller Aberfan Calvinistic Chapel nearby was used as a second mortuary from 22 to 29 October.

By the morning of Saturday 22 October, 111 bodies had been recovered, of which 51 had been identified. At daybreak the Queen’s brother-in-law Lord Snowdon visited and spoke with workers and parents; at 11:00 am Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, visited the scene and talked to rescue workers.

In the early afternoon light rain began falling, which became increasingly heavy; it caused further movement in the tip, which threatened the rescue work and raised the possibility that the area would have to be evacuated.

That evening the mayor of Merthyr Tydfil launched an appeal for financial donations—soon formally named the Aberfan Disaster Fund—to alleviate financial hardship and to help rebuild the area.

The first disaster of its kind to be broadcast live into people’s homes, the plight of Aberfan horrified a watching world.

Donations to the Aberfan Disaster Fund poured in from all over the globe – 90,000 donations, among them an Irish widow’s husband’s gold presentation watch and a mother’s savings for a new winter coat.

It reached a total of £1,750,000, an estimated £20m-plus today – only the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fund has ever outstripped it.

But it was to be branded by the press ‘Aberfan’s second disaster’.

Victims fought a bitter legal battle with its management – the Charity Commission and a group of trustees, local dignitaries – to get access to the money; they were initially refused help to pay for their children’s gravestones.

But the same fund was plundered by the government and handed to the very body which had been found to blame for the tragedy.

Villagers had started a campaign pleading that to continue living in the shadow of the spoil tips was psychological torture. They wanted them gone.

They were dismissed as irrational and told the tips were perfectly safe, that they would not be removed but landscaped instead. But then they had been told they were safe before the disaster.

Driven to distraction by anger and grief, a group of villagers emptied sacks of coal slurry in the reception area of the Welsh Office in protest. They were immediately arrested.

A visibly shaken Secretary of State for Wales, George Thomas – who had met with the miners just minutes before to tell them once again the tips would not be removed – capitulated. The tips would be gone.

But the NCB refused to take financial responsibility so the government and the Charity Commission sanctioned £150,000 to be drawn from the disaster fund to cover the costs.

Then there was the issue of compensation.

To reach an appropriate sum the Charity Commission proposed asking grief-stricken parents ‘exactly how close were you to your child?’; those found not to have been close to their children would not be compensated.

Mercifully, the proposal was never acted upon. The NCB initially offered £50 before raising it to the “generous offer” of £500.

A more substantial sum, it was advised, would have destroyed the working class recipients not used to large amounts of money.

The NCB also refused to pay for the Bethania Chapel to be razed and rebuilt, the congregation unable to worship there given its heartbreaking recent history.

Once again the disaster fund paid for a new chapel to be built in 1970.

Bethania closed in 2007 due to disrepair and a dwindling congregation and was put up for sale.

The neighbouring Capel Aberfan where bodies were taken before burial was burned down by a pyromaniac in 2015.

Its scorched façade remains in Aberfan.

On 23 October assistance was provided by the Territorial Army. This was followed by the arrival of naval ratings from HMS Tiger and members of the King’s Own Royal Border Regiment. That day Wilson announced the appointment of Lord Justice Edmund Davies as the chairman of the inquiry into the disaster; Davies had been born and schooled in the nearby village of Mountain Ash.

A coroner’s inquest was opened on 24 October to give the causes of death for 30 of the children located. One man who had lost his wife and two sons called out when he heard their names mentioned: “No, sir—buried alive by the National Coal Board”; one woman shouted that the NCB had “killed our children”.

The first funerals, for five of the children, took place the following day.

A mass funeral for 81 children and one woman took place at Bryntaf Cemetery in Aberfan on 27 October. They were buried in a pair of 80-foot-long (24 m) trenches; 10,000 people attended.

Because of the vast quantity and consistency of the spoil, it was a week before all the bodies were recovered; the last victim was found on 28 October.

The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh visited Aberfan on 29 October to pay their respects to those who had died. Their visit coincided with the end of the main rescue phase; only one contracting firm remained in the village to continue the last stages of the clean-up.

Marjorie Collins, an Aberfan woman who lost her son in the disaster, remembered the queen’s visit in a 2015 interview with ITV: “They were above the politics and the din and they proved to us that the world was with us, and that the world cared.” Another mother told ITV that no one judged the queen for her delayed response. “We were still in shock, I remember the Queen walking through the mud,” she said. “It felt like she was with us from the beginning.”

Lord Robens of Woldingham served as an MP and Labour government minister before becoming NCB chairman

It is not difficult to understand how grief morphed into a deep, visceral anger.

At the inquest into the deaths, there was uproar with people shouting ‘our children have been murdered’ and ‘mark the death certificate buried alive by the coal board’.

During the subsequent 76-day long tribunal of inquiry – at the time the longest-running inquiry of its kind in British history – the NCB held that it was an act of God – geological factors and heavy rain.

True, it had been raining, heavily, but not unseasonably so for the area and the time of year.

With the evidence stacked against them, towards the end of the inquiry, Lord Robens dramatically admitted the NCB – pilloried for its total absence of tipping policy – was to blame. To have done so earlier on would have spared the victims immeasurable anguish.

The tribunal concluded the disaster was not the result of “villainy” but was “a terrifying tale of bungling ineptitude by many men charged with tasks for which they were totally unfitted, of failure to heed clear warnings, and of a total lack of direction from above”.

No one lost their jobs, was demoted or fined.

In fact, two years later Lord Robens was chosen to chair a review of health and safety which resulted in the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 which continues to regulate practice to this day.

But there is no doubt that many led the rest of their lives with the spectre of Aberfan on their conscience, the distressing consequences of their mistakes published in full view of a horrified world.

David and Ian’s photo-essay on Aberfan was published by every major magazine around the globe and was mentioned in Parliament.

“Aberfan was an extraordinary moment for me,” he says. “It just affected my whole life because it was obscene.

“It brought back to me the idea about Wales. I’d done very little work in Wales, I’d been in London. Suddenly it had put into my mind the idea about going back home.”

Within two years he had left his studio in London’s King’s Road and decamped to south Wales where he lived temporarily in a camper van.

David Hurn in 1969

He went on to set up the prestigious School of Documentary Photography in Newport.

In 2000 he published Wales: Land of My Father, a photographic documentary of the dramatic changes the decades after 1966 would bring for Wales.

He continues with his vocation of photographing the ordinary and every day of Wales, its landscape and people.

Aberfan is different.

– EXCERPT OF A EULOGY BY WRITER GWYN THOMAS BROADCAST ON THE BBC’S TODAY PROGRAMME

When men perished in their hundreds in some eruption of blazing methane, it was possible to view it with a kind of blind ferocity, the sort of ferocity we’ve always used in the face of war.

Men were below the earth doing a grim and unnatural job and sometimes the job would blow up in their faces and most of the doom was underground, out of sight, tucked tactfully away from the public view. But Aberfan is different.

The Aftermath

During the rescue, the shock and grief of parents and villagers was exacerbated by insensitive behaviour from the media—one rescue worker recalled hearing a press photographer asking a child to cry for her dead friends because it would make a good picture.

The response of the general public in donating to the memorial fund, together with over 50,000 letters of condolence that accompanied many of the donations, helped many residents come to terms with the disaster. One bereaved mother said “People all over the world felt for us. We knew that with their letters and the contributions they sent … They helped us build a better Aberfan.”

If you take the old single-track parish road which winds its way to the top of the Taff Valley and look down to the village of Aberfan, at first glance there is little to set it apart from any of the surrounding former mining communities.

The rows of terraces so typical of the south Wales coalfield nestle, virtually unchanged in five decades, at the bottom of the steep valley.

The river Taff which skirts the village, once clogged and black with colliery filth is clear once again and the salmon, otters and kingfishers have returned.

The site of the once mighty Merthyr Vale colliery has all but vanished, landscaped and covered with trees.

Its only relic, the mine sheave wheel on which the village turned for so long, is concreted into the roundabout of a newly-built road around the village.

The bustling high street of family-run shops is also gone.

Aberfan, along with the rest of the disinherited industrialised south Wales Valleys, has struggled with high unemployment and its incumbent social problems.

In the cemetery on the hillside above the village, the two rows of children’s graves are prominent.

The pearl white granite arches have offered a long-awaited redemption from pain for so many parents whose inscriptions have been added over the years as they were reunited with the children they waved goodbye to that cold, foggy, October morning.

The cemetery, maintained by the disaster fund which continues to offer educational grants, is immaculate as is the memorial garden where Pantglas school once stood.

The garden’s tranquillity is not disturbed by the rhythmic whisk of traffic directly above it on the A470, the main route from the valleys into Cardiff, which now cuts through the path of the landslide.

There is not a petal out of place in the borders of flowers which mirror the classroom configuration – a section for standard one, standard two, standard three and standard four.

Down the road on the site of the 18 houses which were destroyed is the Aberfan and Merthyr Vale Community Centre, again built with money from the disaster fund, where children learn to swim and adults attend Zumba and spin classes.

Over the way a new school – Ynysowen Community Primary – was opened by the Queen in 2012 and is surrounded by playing fields created by the tonnes of shale waste cleared from the tips.

Jeff Edwards and the Queen in 2012 at the opening of Ynysowen Community Primary

As a result of Aberfan, legislation passed in 1969 put in place a strict policy on the practice of tipping.

This in turn led to legislation being amended and reviewed across the world.

The majority of tips in south Wales have been removed and the valleys, like Aberfan’s, are green again.

But look long enough and the outline of where they once stood above the village can be clearly seen.

Despite fervent efforts to cultivate it, the grass which grows over the site of the tips is a different colour, a coarse, sickly yellow, as if nature itself refuses to ‘give up the ghost’ and forgive the “appalling calamity” of the past.

It is consoling to think the pain which consumed the village – the shattered lives and unjust treatment of its working men and women – has made a significant difference, informing and influencing countless changes over the past 50 years.

The majority of those men and women may not be around today.

But the white-arch graves and the tainted grass above them will serve as an indelible reminder for who knows how many generations to come of their part in a defining moment in our nation’s history.

For that dreadful day 50 years ago would ensure that, in the stirring words of the late, great broadcaster, writer and poet Gwyn Thomas, the ‘true voice of the English-speaking valleys’, Aberfan is different.

Credits

Author Ceri Jackson Online Production Gwyndaf Hughes and Sophie Mutton Photography Magnum Photos (David Hurn and Ian Berry)Getty Images Associated Press Alamy Old Merthyr Tydfil Report Digital Roger Vadim Gaynor Madgwick Gerald Kirwan Built with Shorthand Publication date 21 October 2016

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands