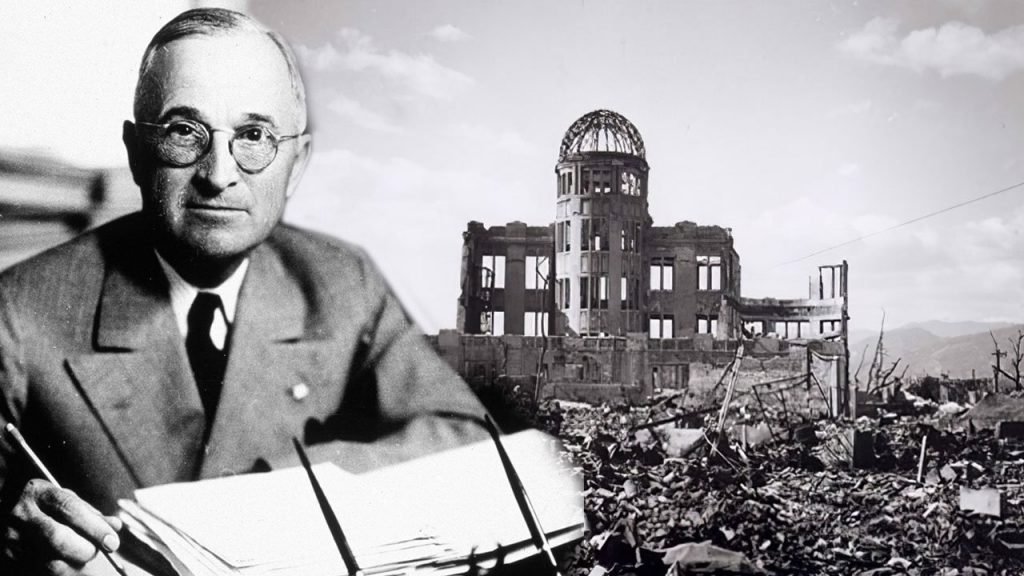

In the pre-dawn hours of August 6, 1945, a B-29 bomber named Enola Gay lifted into the summer sky above Tinian Island. Its payload, a single bomb innocuously nicknamed “Little Boy,” would tear open not just the morning sky above Hiroshima, but the very fabric of human civilization.

At 8:15 a.m., in a blinding flash that turned shadows into stone and morning into nuclear night, America crossed a threshold from which humanity could never return. The bomb that devastated Hiroshima, followed three days later by another that obliterated Nagasaki, killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people—mostly civilians going about their morning routines. They remain the only nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, a distinction that haunts us still.

The official narrative was clear and remains stubbornly persistent: these acts of unprecedented destruction were necessary to force Japan’s surrender, to prevent a costly mainland invasion, to save American lives. By July 1945, conventional bombing had already laid waste to 64 Japanese cities. Germany had surrendered months earlier.

The Allies, through the Potsdam Declaration, had demanded Japan’s unconditional surrender, threatening “prompt and utter destruction.” The Japanese government’s decision to ignore this ultimatum sealed the fate of two cities and their inhabitants.

In the final year of World War II, the Allies prepared for a costly invasion of the Japanese mainland. This undertaking was preceded by a conventional and firebombing campaign that devastated 64 Japanese cities.

The consent of the United Kingdom was obtained for the bombing, as was required by the Quebec Agreement, and orders were issued on 25 July by General Thomas Handy, the acting Chief of Staff of the United States Army, for atomic bombs to be used against Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata, and Nagasaki.

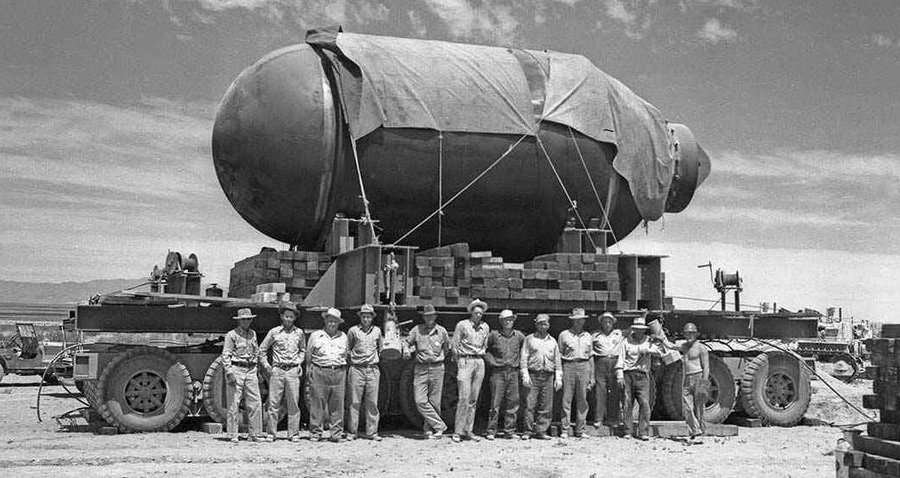

These targets were chosen because they were large urban areas that also held militarily significant facilities. On 6 August, a Little Boy was dropped on Hiroshima, to which Prime Minister Suzuki reiterated the Japanese government’s commitment to ignore the Allies’ demands and fight on.

Three days later, a Fat Man was dropped on Nagasaki. Over the next two to four months, the effects of the atomic bombings killed between 90,000 and 146,000 people in Hiroshima and 39,000 and 80,000 people in Nagasaki; roughly half occurred on the first day. For months afterward, many people continued to die from the effects of burns, radiation sickness, and injuries, compounded by illness and malnutrition. Though Hiroshima had a sizable military garrison, most of the dead were civilians.

Japan surrendered on August 15, six days after Nagasaki and the Soviet Union’s declaration of war. The papers were signed on September 2, officially ending World War II. But the debate over these three August days has never ended.

Was this display of apocalyptic force necessary? Were there alternatives? What does it mean when we justify the instantaneous annihilation of civilian populations in the name of peace?

Scholars have extensively studied the effects of the bombings on the social and political character of subsequent world history and popular culture, and there is still much debate concerning the ethical and legal justification for the bombings. Supporters believe that the atomic bombings were necessary to bring a swift end to the war with minimal casualties; critics dispute how the Japanese government was brought to surrender, and highlight the moral and ethical implications of nuclear weapons and the deaths caused to civilians.

Where did such devastating weapons come from and who created them…

We knew the world would not be the same.

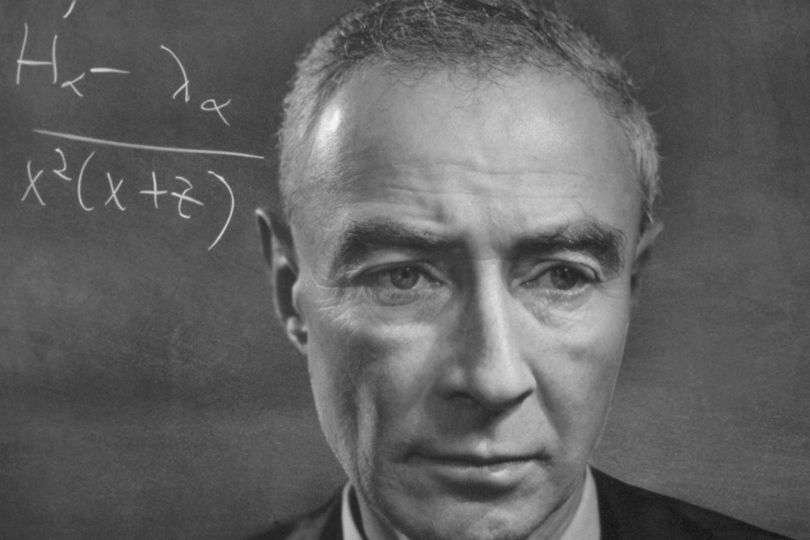

J. Robert Oppenheimer was born in New York City on April 22, 1904, to Julius Oppenheimer, a wealthy Jewish textile importer who had immigrated to the United States from Germany in 1888, and Ella Friedman, a painter. Julius came to the United States with no money, no baccalaureate studies, and no knowledge of the English language. He got a job in a textile company and within a decade was an executive with the company. Ella was from Baltimore. The Oppenheimer’s were non-observant Ashkenazi Jews.

Oppenheimer was initially educated at Alcuin Preparatory School; in 1911, he entered the Ethical Culture Society School. This had been founded by Felix Adler to promote a form of ethical training based on the Ethical Culture movement, whose motto was “Deed before Creed”. His father had been a member of the Society for many years, serving on its board of trustees from 1907 to 1915. Oppenheimer’s religion and formal education became an important part of his and the story of the world.

During the 1920s, Oppenheimer remained uninformed on worldly matters. He claimed that he did not read newspapers or listen to the radio and had only learned of the Wall Street crash of 1929 while he was on a walk with Ernest Lawrence some six months after the crash occurred.

He once remarked that he never cast a vote until the 1936 presidential election. However, from 1934 on, he became increasingly concerned about politics and international affairs. In 1934, he earmarked three percent of his annual salary—about $100 (equivalent to $1,935 in 2020)—for two years to support German physicists fleeing from Nazi Germany. During the 1934 West Coast Waterfront Strike, he and some of his students, including Melba Phillips and Bob Serber, attended a longshoremen’s rally. Oppenheimer repeatedly attempted to get Serber a position at Berkeley but was blocked by Birge, who felt that “one Jew in the department was enough”.

Oppenheimer’s mother died in 1931, and he became closer to his father who, although still living in New York, became a frequent visitor in California. When his father died in 1937 leaving $392,602 to be divided between Oppenheimer and his brother Frank, Oppenheimer immediately wrote out a will that left his estate to the University of California to be used for graduate scholarships.

Like many young intellectuals in the 1930s, he supported social reforms that were later alleged to be communist ideas. He donated to many progressive causes that were later branded as left-wing during the McCarthy era. The majority of his allegedly radical work consisted of hosting fundraisers for the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War and other anti-fascist activity.

He never openly joined the Communist Party USA (CPUSA), though he did pass money to leftist causes by way of acquaintances who were alleged to be Party members. In 1936, Oppenheimer became involved with Jean Tatlock, the daughter of a Berkeley literature professor and a student at Stanford University School of Medicine. The two had similar political views; she wrote for the Western Worker, a Communist Party newspaper.

The FBI opened a file on Oppenheimer in March 1941. It recorded that he attended a meeting in December 1940 at Chevalier’s home that was also attended by the Communist Party’s California state secretary William Schneiderman, and its treasurer Isaac Folkoff.

The FBI noted that Oppenheimer was on the Executive Committee of the American Civil Liberties Union, which it considered a Communist front organisation. Shortly thereafter, the FBI added Oppenheimer to its Custodial Detention Index, for arrest in case of national emergency.

Debates over Oppenheimer’s Party membership or lack thereof have turned on very fine points; almost all historians agree he had strong left-wing sympathies during this time and interacted with Party members, though there is considerable dispute over whether he was officially a member of the Party. At his 1954 security clearance hearings, he denied being a member of the Communist Party, but identified himself as a fellow traveller, which he defined as someone who agrees with many of the goals of Communism, but without being willing to blindly follow orders from any Communist party apparatus.

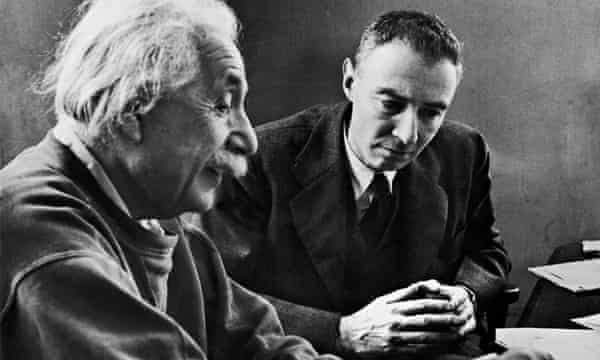

But for all his Left-wing credentials and associations within arguably the home of the capitalist industrial arms industry, Oppenheimer was to leave an outsized mark on history. For his crucial role in the Manhattan Project that during World War II produced the first nuclear weapons, he’s now remembered as the ”father of the atomic bomb. Oppenheimer is also remembered for his poignant words captured on video.

Watch this video we remastered.

We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad-Gita. Vishnu is trying to persuade the prince that he should do his duty and to impress him takes on his multi-armed form and says, “Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” I suppose we all thought that one way or another. -Robert Oppenheimer witnessing the first detonation of a nuclear weapon on July 16, 1945.

That one piece of Hindu scripture that ran through the mind of Robert Oppenheimer: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds” is perhaps the most well-known line from the Bhagavad-Gita, and according to James Temperton from weird also the most misunderstood.

Oppenheimer died at the age of sixty-two in Princeton, New Jersey on February 18, 1967. As wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory, the birthplace of the Manhattan Project, he is rightly seen as the “father” of the atomic bomb. “We knew the world would not be the same,” he later recalled. “A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent.” Oppenheimer, watching the fireball of the Trinity nuclear test, turned to Hinduism.

While he never became a Hindu in the devotional sense, Oppenheimer found it a useful philosophy to structure his life around. “He was obviously very attracted to this philosophy,” says Rev Dr Stephen Thompson, who holds a PhD in Sanskrit grammar and is currently reading a DPhil at Oxford University on other aspects of the language and Hindu faith. Oppenheimer’s interest in Hinduism was about more than a soundbite, it was a way of making sense of his actions.

The Bhagavad-Gita is 700-verse Hindu scripture, written in Sanskrit, that centres on a dialogue between a great warrior prince called Arjuna and his charioteer Lord Krishna, an incarnation of Vishnu. Facing an opposing army containing his friends and relatives, Arjuna is torn. But Krishna teaches him about a higher philosophy that will enable him to carry out his duties as a warrior irrespective of his personal concerns. This is known as the dharma, or holy duty. It is one of the four key lessons of the Bhagavad-Gita: desire or lust; wealth; the desire for righteousness or dharma; and the final state of total liberation, or moksha.

Seeking his counsel, Arjuna asks Krishna to reveal his universal form. Krishna obliges, and in verse twelve of the Gita he manifests as a sublime, terrifying being of many mouths and eyes. It is this moment that entered Oppenheimer’s mind in July 1945. “If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendour of the mighty one,” was Oppenheimer’s translation of that moment in the desert of New Mexico.

In Hinduism, which has a non-linear concept of time, the great god is not only involved in the creation, but also the dissolution. In verse thirty-two, Krishna speaks the line brought to global attention by Oppenheimer. “The quotation ‘Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds’, is literally the world-destroying time,” explains Thompson, adding that Oppenheimer’s Sanskrit teacher chose to translate “world-destroying time” as “death”, a common interpretation. Its meaning is simple: irrespective of what Arjuna does, everything is in the hands of the divine.

“Arjuna is a soldier, he has a duty to fight. Krishna not Arjuna will determine who lives and who dies and Arjuna should neither mourn nor rejoice over what fate has in store, but should be sublimely unattached to such results,” says Thompson. “And ultimately the most important thing is he should be devoted to Krishna. His faith will save Arjuna’s soul.” But Oppenheimer, seemingly, was never able to achieve this peace. “In some sort of crude sense which no vulgarity, no humour, no overstatements can quite extinguish,” he said two years after the Trinity explosion, “the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose.”

“He doesn’t seem to believe that the soul is eternal, whereas Arjuna does,” says Thompson. “The fourth argument in the Gita is really that death is an illusion, that we’re not born and we don’t die. That’s the philosophy really: that there’s only one consciousness and that the whole of creation is a wonderful play.” Oppenheimer, it can be inferred, never believed that the people killed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki would not suffer. While he carried out his work dutifully, he could never accept that this could liberate him from the cycle of life and death. In stark contrast, Arjuna realises his error and decides to join the battle.

“Krishna is saying you have to simply do your duty as a warrior,” says Thompson. “If you were a priest you wouldn’t have to do this, but you are a warrior and you have to perform it. In the larger scheme of things, presumably The Bomb represented the path of the battle against the forces of evil, which were epitomised by the forces of fascism.”

For Arjuna, it may have been comparatively easy to be indifferent to war because he believed the souls of his opponents would live on regardless. But Oppenheimer felt the consequences of the atomic bomb acutely. “He hadn’t got that confidence that the destruction, ultimately, was an illusion,” says Thompson. Oppenheimer’s apparent inability to accept the idea of an immortal soul would always weigh heavy on his mind.

Oppenheimer ethical training based on the Ethical Culture movement, whose motto was “Deed before Creed” combined an appeal to universal principles with moral particularism, which holds that the unique circumstances of a particular case must be carefully considered to determine the moral choice in that case. One could be excused for thinking all the while Oppenheimer’s aim was the defeat of fascism and the Nazis however distasteful the method.

Support Independent Journalism Today

Our unwavering dedication is to provide you with unbiased news, diverse perspectives, and insightful opinions. We're on a mission to ensure that those in positions of power are held accountable for their actions, but we can't do it alone. Labour Heartlands is primarily funded by me, Paul Knaggs, and by the generous contributions of readers like you. Your donations keep us going and help us uphold the principles of independent journalism. Join us in our quest for truth, transparency, and accountability – donate today and be a part of our mission!

Like everyone else, we're facing challenges, and we need your help to stay online and continue providing crucial journalism. Every contribution, no matter how small, goes a long way in helping us thrive. By becoming one of our donors, you become a vital part of our mission to uncover the truth and uphold the values of democracy.

While we maintain our independence from political affiliations, we stand united against corruption, injustice, and the erosion of free speech, truth, and democracy. We believe in the power of accurate information in a democracy, and we consider facts non-negotiable.

Your support, no matter the amount, can make a significant impact. Together, we can make a difference and continue our journey toward a more informed and just society.

Thank you for supporting Labour Heartlands